By ANDREA JOYCE LUCAS

If Kristel Tejada were alive today, she would have been a graduating behavioral sciences student in UP Manila. She would also be on her way to medical school, as she dreamed of being a doctor, of bringing medical assistance to people in far-flung places.

All that remains of Kristel’s dreams now are memories, though so much has happened to her family since her passing. Tatay Chris now has a job at the Manila City Hall, and Nanay Blessie busies herself with caring for her children and activities at her local church.

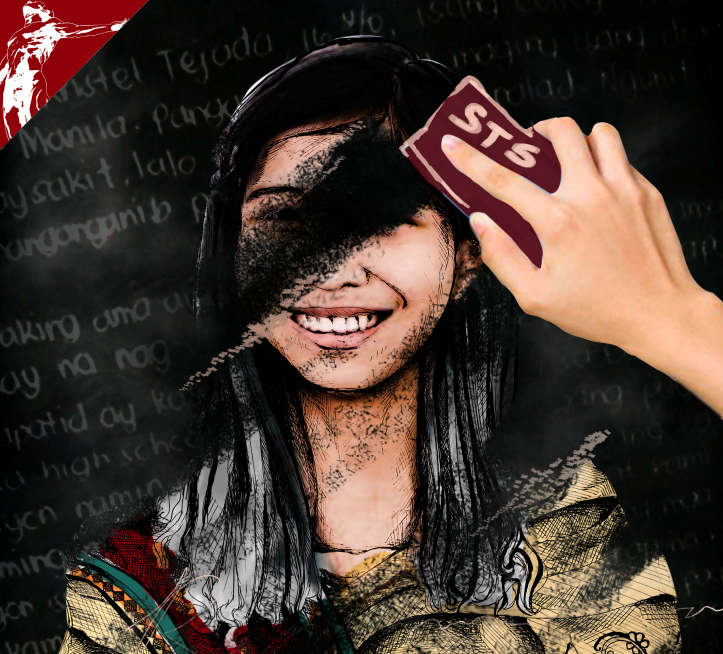

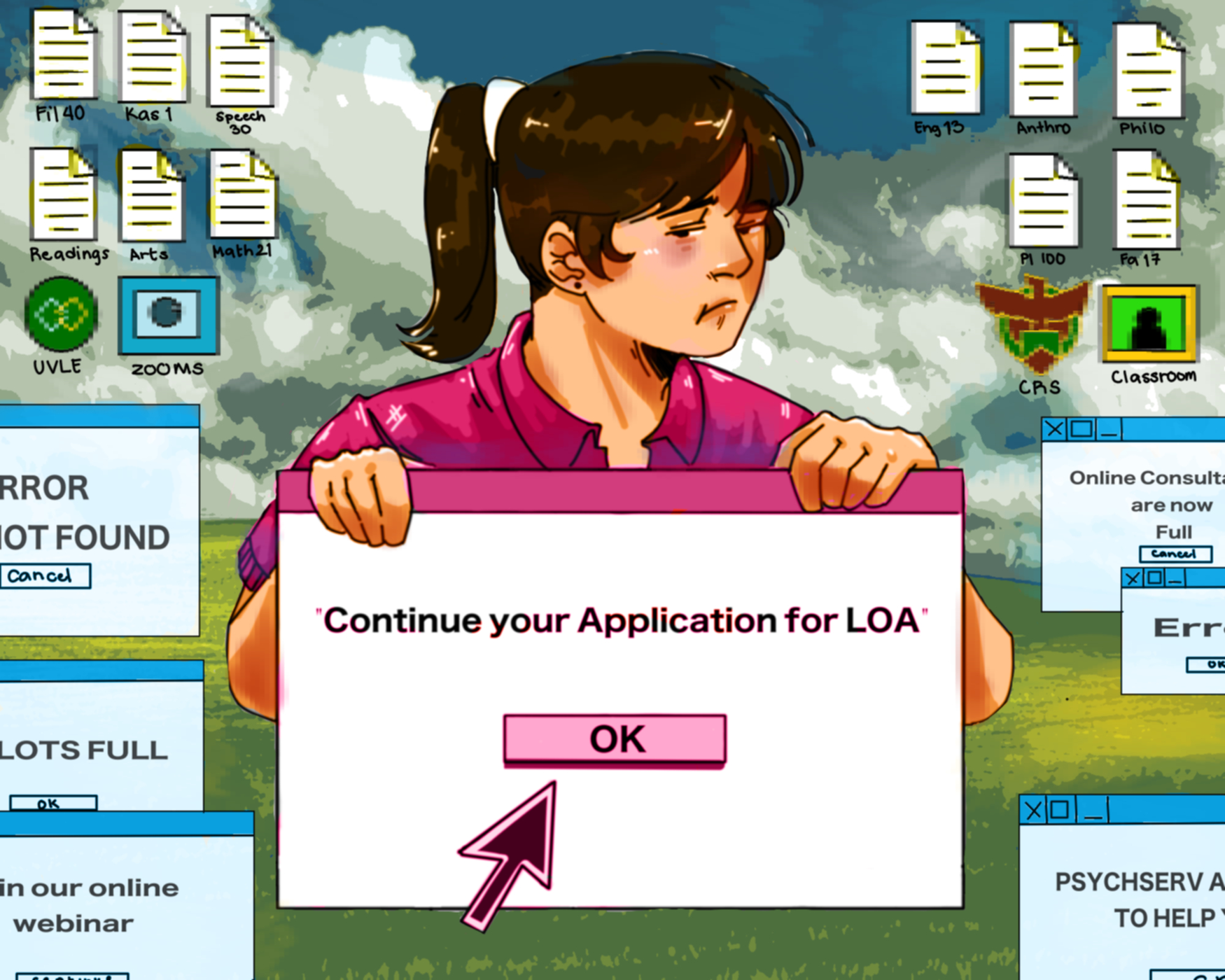

So much has happened to UP as well since Kristel ended her own life three years ago, after she was forced to quit college due to unpaid tuition – the new Socialized Tuition System (STS), budget cuts, the academic calendar shift. Yet these changes have not been for the better, there would be no guarantee the story would have been any different if Kristel were still alive today.

Dreaming Big

Nanay Blessie describes her daughter as a sweet and kind girl who cared deeply about other people’s welfare and had a lot of friends. Kristel was particularly close to her younger brother, Khristof. “Kung papansinin mo, magkamukha nga sila,” she laughs.

Kristel was an outstanding student. She finished elementary and high school with excellent marks at a Catholic school, though she had to rely on scholarship to stay in school. Even in college, she showed as much enthusiasm for learning. One of her professors in UP Manila, Professor Andrea Martinez, recalls her as a student who took her studies seriously, but was also sweet and friendly to her classmates. The professor would often let Kristel attend her classes even when she was barred from enrolling, because she knew how much the girl wanted to study. Kristel once gave her a rose as a token of her gratitude.

Kristel’s humble background did not stop her from dreaming big. When Kristel entered UP, the Tejadas thought that her future was bright and full of promise. They never knew dreams had a price and would cost them their daughter’s life.

Oppressive Policies

Three years were not enough to make Tatay Chris and Nanay Blessie forget how difficult it was to send Kristel to UP. Back then, Tatay Chris worked as a part-time taxi driver, while Nanay Blessie stayed at home to mind the house and their three younger children. It was a struggle for them to make ends meet, especially since Kristel’s younger siblings were studying as well. “Iyon ‘yung panahon na talagang bagsak kami,” said Nanay Blessie.

When she entered UP in 2012, Kristel’s matriculation fees were assessed under the Socialized Tuition and Financial Assistance Program (STFAP). Kristel was assigned a P300-per-unit tuition under Bracket D, but her family could even hardly afford their daughter’s school allowance. Their appeals for a lower bracket were denied, so all Kristel and her parents could do at the time was to rely on tuition loans from UP to finance her schooling. There were days when Kristel had to skip meals or sell snacks to her classmates just to cover the costs of her daily expenses.

But loans were only a temporary solution–deferring only the payments that the Tejadas are still obliged to settle. Tatay Chris laments that if only there were more subsidy for state universities like UP, if education truly were considered a right of all youth, there would be no need for students to shoulder the costs of their education. It could have gone a long way in helping Kristel and other youth achieve their dreams.

In the recent years, the government has allotted funds to UP that fall short of what it needs. This resulted in staggering budget cuts: P1.43 billion in 2014 and P2.2 billion in 2015.

Many other individuals and progressive groups have rallied behind the call for an increase in state subsidy for UP, but the national government would not hear any of it. In December 2013, just months after Kristel’s death, the UP administration implemented the Socialized Tuition System (STS), its proposed solution to the now infamous STFAP.

However, STS also falls short of addressing the problems STFAP had. While STS did away with much of the long lines and the paperwork, it has been fundamentally the same. Tatay Chris points out that UP tuition remains as expensive as ever, an observation that is consistent with the official figures from the Office of Scholarships and Student Services. As of the second semester of the current academic year, only eight percent, or less than one out of ten UP students receive free tuition under the STS.

Continuing Struggles

Nowadays, the Tejadas are slowly coming to terms with their loss. “Noong ipinanganak ko ‘yung bunso naming si Kristal, parang ipinanganak ko ulit si Kristel.” Kristal even looks like Kristel, Nanay Blessie notes, and this was why they chose for her a similar name to Kristel. Little by little, she and Tatay Chris have begun to raise their younger children to know and remember Kristel.

Yet the family is not alone in remembering Kristel. “Kahit ngayon, may mga close friends siya na dumadalaw sa puntod niya,” shares Nanay Blessie. They have also met a lot of other friends since Kristel’s death–friends who have promised to continue fighthing against the opressive student policies and conditions that led to her death. “Sapat na ‘yung isang Kristel,” Tatay Chris says.

Nothing will ever replace Kristel in their lives, but Tatay Chris and Nanay Blessie still hope their children would be able to get into UP like their sister Kristel, and they are determined not to let the past repeat itself. Like Kristel’s friends, they vow to continue to lend their voice to the fight for the right to an accessible and quality education.

Published in print in the Collegian’s March 17, 2016 issue.