Marlito Ocon has an unenviable job, even by Philippine General Hospital (PGH) standards. He has a 24-hour shift that starts in the morning and ends the next day. Thrice a week, he dons the instantly recognizable full personal protective equipment for medical frontliners and makes his hospital rounds, visiting 25 to 30 patients each time.

But Ocon does not check hospital charts or dispense medication to sick patients. A Jesuit priest who serves as the PGH chaplain, Ocon is there to administer the Catholic last rites, a series of ministrations and sacraments to dying individuals. As the pandemic rages on, his job becomes more and more essential and, like Luke the Evangelist, a Greek physician called to minister to spiritual infirmities, Ocon, too, must cater to the growing needs of the suffering faithful.

The designation of the PGH as a COVID-19 referral hospital last April 2020 has upended the lives of the staff working there, including that of Ocon. An atmosphere of perpetual uncertainty and fear descended upon the place already overwhelmed, dilapidated, and underfunded even before the pandemic. It is in this place where around 800 COVID-19 patients breathed their last, often in pain, silence, and solitude. Considering the current projections, it is also where countless more will do so.

The recent COVID-19 surge has proven to be far more challenging for the PGH than the first one. The hospital is already filled to the brim with patients, and all the intensive care unit (ICU) beds are already occupied. What is especially disconcerting, Ocon said, is that news of an available ICU bed is bittersweet—a relief for those on the waiting list, which is becoming longer by the day, but also probably a sign that the previous occupant had already passed on.

“Ang kalaban mo dito hindi lang ‘yung number of patients, but it’s also an emotional battle. You meet people who are dying. Sometimes there are three or four of them dying in a single family, the mother and father would die, their children would die,” Ocon said. “This could also drain you emotionally. Hindi ka lang mapapagod physically, but also mentally and emotionally.”

Hospital protocols require patients with COVID-19 to be in strict isolation to minimize further infection. Even family members are not allowed to visit and take care of their relatives, no matter how serious the condition is. This means that, in addition to the disease, patients will have to contend with the accompanying dread and anxiety of being alone.

A plaintive Ocon recounted how he had administered last rites to a married couple who got infected and admitted at the same time. They were actually only in adjacent rooms, but they died without ever seeing each other. Another notable case he shared was that of another couple who had arrived at the hospital together, but only one of them went home. Sadly, he said, this is a recurring reality for many. “Sabay kayong pumapasok sa ospital, pero hindi niyo alam kung sabay pa kayong lalabas,” he said.

For many of the COVID-19 patients who passed away in PGH, Ocon’s words and prayers were some of the last—and for some, the only—words they heard. “Wala silang makausap, e, except for those who were able to have a video call with their family. Pero karamihan nasa charity ward, galing mahihirap na pamilya, karamihan wala namang phone. Kung meron man, walang load, so kinakausap namin,” he said. “It’s a big thing for them na makausap.”

The grieving process that occurs after the death of a loved one was also upended by the pandemic. This is especially painful, Ocon said, for families that have multiple members requiring hospitalization. “Paglabas nakabalot na ng bag, you will only see them after cremation. Imagine, the last time you saw them was when you were both admitted. Kung makakauwi ka, maabutan mo na lang sila sa bahay, nasa urn na. Napakalungkot na in struggle ‘yung loved one, pero hindi man lang mapuntahan o mahawakan,” Ocon said. “Napakalungkot ang pagkamatay na dulot ng COVID.”

The recent surge, Ocon admitted, has not only been taxing for him physically and emotionally, but also spiritually. “Marami tayong hindi naiintindihan, bakit ito nangyayari sa isang tao, sa isang young mother, sa isang promising doctor, a young father, his very young daughter, and yet sila pa natamaan. Mahirap intindihin, but it can only be seen clearly through the eyes of faith,” he said. “So the only thing I bring is faith.”

Ocon’s initial journey towards faith was not the clear-cut path that many of his Jesuit brothers had. He did not attend a Jesuit school in college, nor took up a related degree like philosophy. “I was a civil engineer who trained and worked as a ship design engineer in Japan for four years,” Ocon said.

But the infamous calling eventually came for him in Japan—the often cited persistent thoughts of doing something greater—“magis,” as the Jesuits refer to it, the call to do greater things for Christ and for others. A chance encounter with a film about the first Jesuit missionaries in Japan solidified his resolve to join the order in 1999, and so began his ministry.

“My first assignment, which lasted for three years, was in the leper colony of Culion, Palawan,” he said. Since the Spanish period, the Society of Jesus has been running a school on the island that catered to the most ostracized people in the country—the so-called “ketongin” or those afflicted with leprosy and had the unmistakable skin sores that made others shun them out of fear of getting infected.

After serving as a chaplain in the Ateneo de Zamboanga, Ocon was eventually assigned to yet another institution for the sick and suffering: the Philippine General Hospital. “It is very challenging here in PGH,” he admitted. “Here, you don’t just cater to the patients’ sacramental and spiritual needs, you are also called to cater to their material needs.”

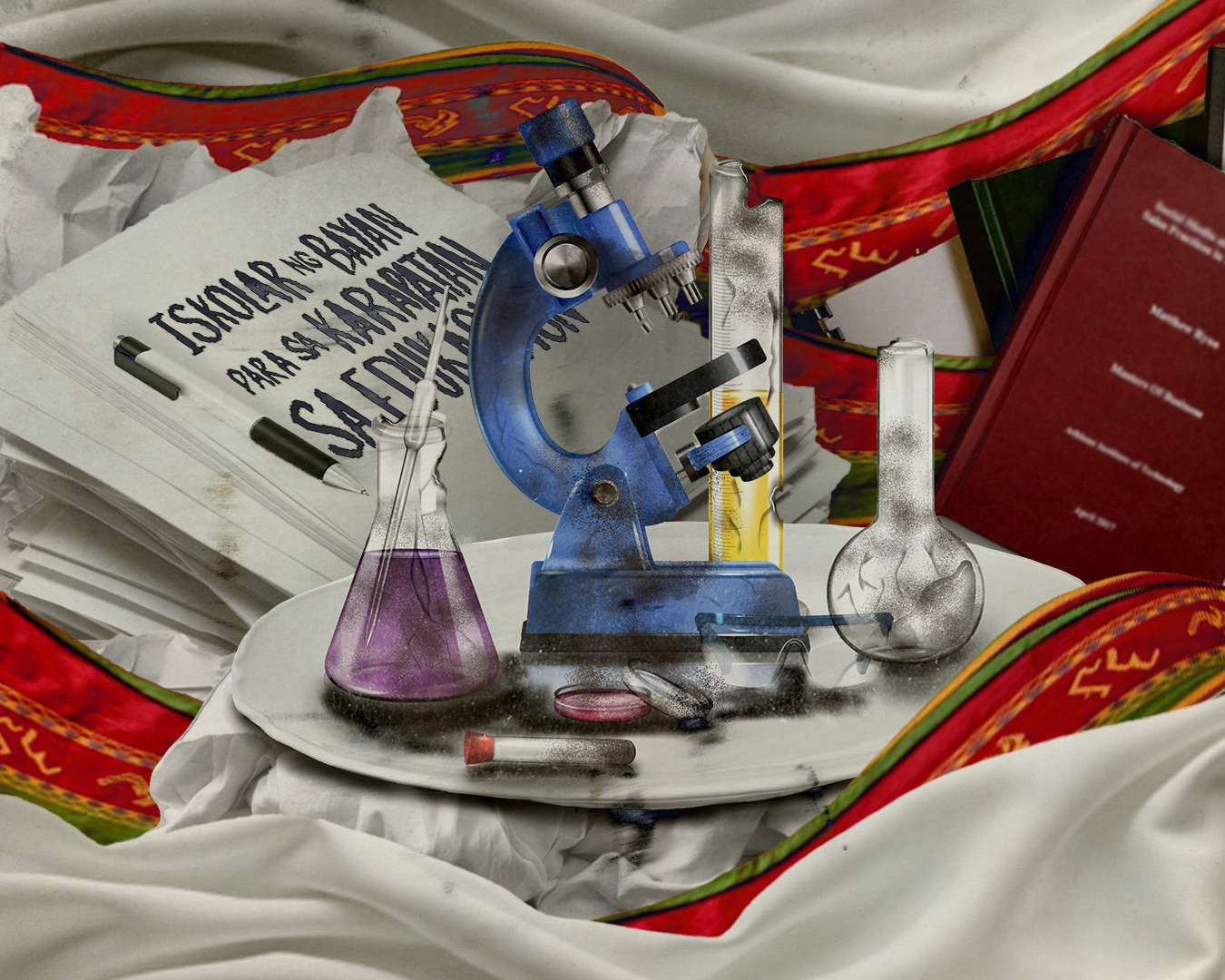

As a tertiary state-owned institution designated as the national government referral center, the PGH is the first and final bastion of hope for those afflicted with a severe illness compounded by the malady of poverty. Ocon noted that, most of the time, not even the charity wards available at a discount would suffice for all the countless poor Filipinos in dire need of health care in the hospital. So the chaplaincy, he said, always tries to provide food, medicine, even groceries, to the patients and their families in need.

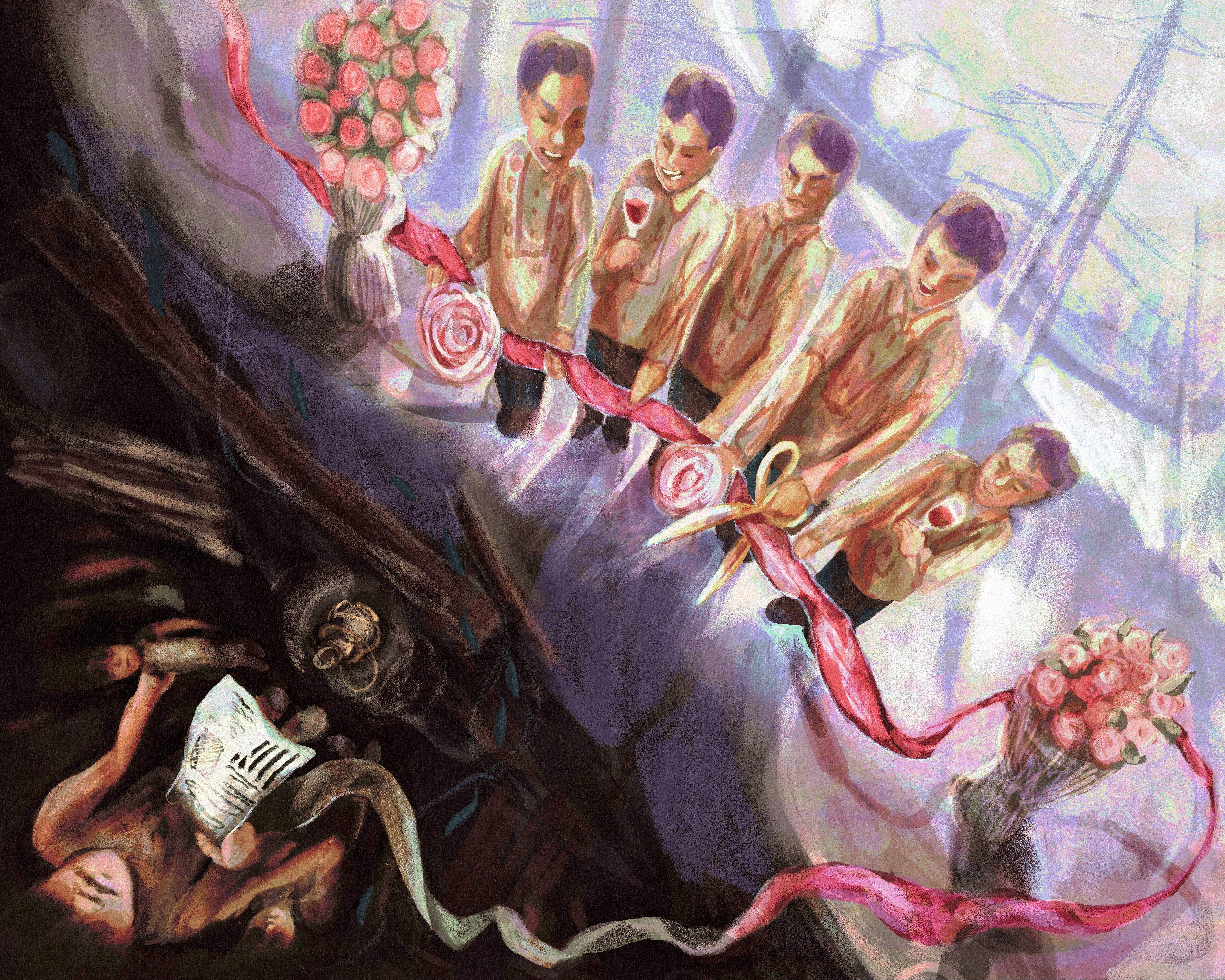

In his time as the PGH chaplain, Ocon bore witness to so much suffering from the poor and powerless who, for so long as he can remember, have been relegated to the margins in the supposed march to development. So naturally, news of the dolomite beach constructed near the hospital struck a nerve with the priest, who went on a veritable jeremiad against the long list of problems the hospital faces that have become so much worse because of the pandemic. The millions of pesos spent on the beautification project should have gone to health care instead, he said.

“When PGH was made a COVID referral hospital, there was a promise of all these benefits, additional P500 hazard pay, all that, pero natapos taon, walang na-release,” lamented Ocon. “Kahit hindi ako beneficiary doon, sumasama loob ko kasi nakikita ko talaga hirap ng health workers, na araw-araw napapagod, pinipilit maglakad papasok kahit na umuulan.”

Asked of what he prayed for in these dark and terrible days, Ocon responded with a simple call for more funding and attention to the health care system in the country, to PGH in particular. That the supposed national referral hospital is sorely lacking in manpower, equipment, and supplies is painfully apparent, he said.

As the pandemic drags on, Ocon’s endless job of comforting the dying will most certainly continue. Following Luke who followed Christ without hesitation, Ocon, too, is called to tread the same path of service as a doctor to the sick. And like Luke, his vocation means so much more than tending to diseases of the body. ●