With both mainstream and government-run media coming under scrutiny these past few weeks due to their coverage of the COVID-19 crisis, some have pitched the idea of establishing an independent public broadcasting system in the country.

Mainstream media have been criticized for their supposed inappropriate questions posed to sources. In one recent instance, Tina Panganiban-Perez of GMA News directly asked Ana Patricia Non, the organizer behind the Maginhawa community pantry, whether she had links with the communist movement. Then, last week, Malacañang ordered state-run media organizations to provide regular updates showing that the country was “faring better” than other countries in terms of pandemic response, according to a leaked memorandum from the Presidential Communications and Operations Office (PCOO) dated April 27.

“Kailangan i-review nila yung editorial policies nila (state media), and have one which is like the professional media,” Philippine Press Institute executive director Ariel Sebellino told the Collegian.

For Sebellino, state-run media organizations have been too busy sharing government propaganda instead of delivering content that conforms to the highest journalistic standards and ethics. The PCOO fiasco was just the latest of such attempts to echo a state-sanctioned narrative.

The PCOO has since acknowledged the existence of the leaked document. “There is nothing wrong with this, nor is it a lie. It is simply amplifying facts,” said Virginia Arcilla-Agtay, head of the PCOO News and Information Bureau (NIB) in a statement, April 28.

Transforming the Current System

The prospects of a government-owned yet editorially independent news organization might be too far-fetched in the Philippine context, according to Sebellino, as it would entail a radical restructuring of the way state-run media operate.

Presently, the People’s Television Network, Inc. (PTV4), the Philippine News Agency (PNA), the Philippine Information Agency (PIA), and the Philippine Broadcasting Service (Radyo Pilipinas) are under the umbrella of the PCOO, which is part of the Office of the President.

“Kailangan ang magpapatakbo do’n, mayroong sense of integrity. It would introduce such an overhaul, in the processes and dynamics, from news gathering to news presentation to even how much percentage in the news report ay puro government-side,” Sabellino explained.

In terms of more structural reforms, media organizations should be divorced from the executive branch and operate more independently, suggested Danilo Arao, a professor at the UP Diliman Department of Journalism. This would mean constituting an impartial board or committee to govern these organizations. Professional media practitioners should administer any government-owned media outfit, akin to the UK’s British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Board, if it aims to achieve independence.

“You can have government-funded agencies, but there is independence insofar as the management would be concerned. Government representatives may be there, but they should be in the minority,” Arao told the Collegian.

A public broadcasting system steered by media practitioners and not by government bureaucrats would not only be a more independent organization, but also a professional one—an integral part in running a news outfit.

“These are not just skills, they are not being taught how to write the news—that’s one part of the training. More than that, we need to provide the theoretical, empirical and normative standards,” Arao said.

Aside from its pro-government skew, the PNA, for instance, has republished in their social media accounts the photograph of the remains of Bayan Muna Eufemia Cullamat’s slain daughter. In an apparent gaffe in 2017, the PNA also mistook the logo of fruit producer Dole Philippines as that of the Department of Labor and Employment.

“Ang structural reform should go hand in hand with really putting people who will run the government's media as professionally, as ethically, as credibly, as responsibly as it should be,” Sebellino said.

Funding

Creating an independent and professional public broadcasting system would obviously cost money. Improving the country’s government-owned news outfits would mean increased operational costs and require greater investment in better and newer infrastructure.

In the British model, the BBC is funded by annual television license fees paid by households. Currently, this costs around P10,000. Under this scheme, up to three-fourths of the BBC’s annual budget is funded directly by its subscribers, while the remaining amount is sourced from commercial activities like advertising.

But, Arao argues, this model may not be feasible in the Philippine context. Requiring households to pay an annual subscription just to be able to access and consume public broadcasting products might just be similar to that of a paid TV subscription.

In the most practical sense, Filipino families simply have other expenses to deal with.

“Even in the UK, where disposable income is relatively high compared to ours, many of them are also complaining [about] why they need to pay so much just to finance the BBC,” Arao said. “Here, it’s much worse. The [Filipinos’] purchasing power is very, very low.”

The Philippine government could maintain the current funding model of the various state-run media organizations—funded fully by government revenues. The PCOO’s current budget amounts to more than P1.5 billion. Of this amount, however, only a measly P4.3 million is allocated as the NIB and PIA’s capital outlay—the budget meant for the purchase of new equipment or infrastructure programs.

If the country were to implement a public broadcasting system, the government news organizations’ budget would need to be increased. Realigning allocation might be one way to fund them, Arao added.

The insurance of stable, annual funding also adds to the independence of a taxpayer-funded news organization. That way, it need not tailor-fit its content to any national administration’s views to become commercially viable. This could also result in better and more relevant content.

“[A public broadcasting system] can take on the challenge of setting up programs that are not so profitable. That’s why, you can concentrate more on the content, you can focus your energy on producing high-quality shows without thinking at the back of your mind whether or not it would click with the advertisers,” Arao argued.

Push for Creation

Both Sebellino and Arao are, however, doubtful if the present administration would be willing to establish an independent, government-owned media. After all, lending them editorial independence would entail losing a significant part of the government’s propaganda tool.

For Sebellino, modern democracies put up public broadcasting systems to disseminate information more effectively. Though propaganda may be inevitable, it should not overshadow the truth-telling aim of journalism. “Kailangan ng tao yung access to information na parehong side—nasa government, nasa private, alternative media, nasa baba, nasa taas—kasi it makes for a pluralistic society,” he said.

Early in President Rodrigo Duterte’s term, PCOO Secretary Martin Andanar touted the possibility of reorganizing PTV 4 similar to the BBC. A month after Duterte’s term began, he advocated for improving the news network to be on par with international standards, which include editorial independence.

There were also legislative efforts for this push. In the 17th Congress, at least two bills were filed at the House of Representatives creating a People’s Broadcasting Corporation (PBC). Two bills are also pending in the lower house presently.

But as the president’s term progressed, these efforts slowly died. Andanar, or any government official, was never heard from again about any plans for providing government news agencies with editorial independence. Instead, they have become more entangled in spreading state propaganda. Measures proposing the PBC also never came out of committee deliberations in the House.

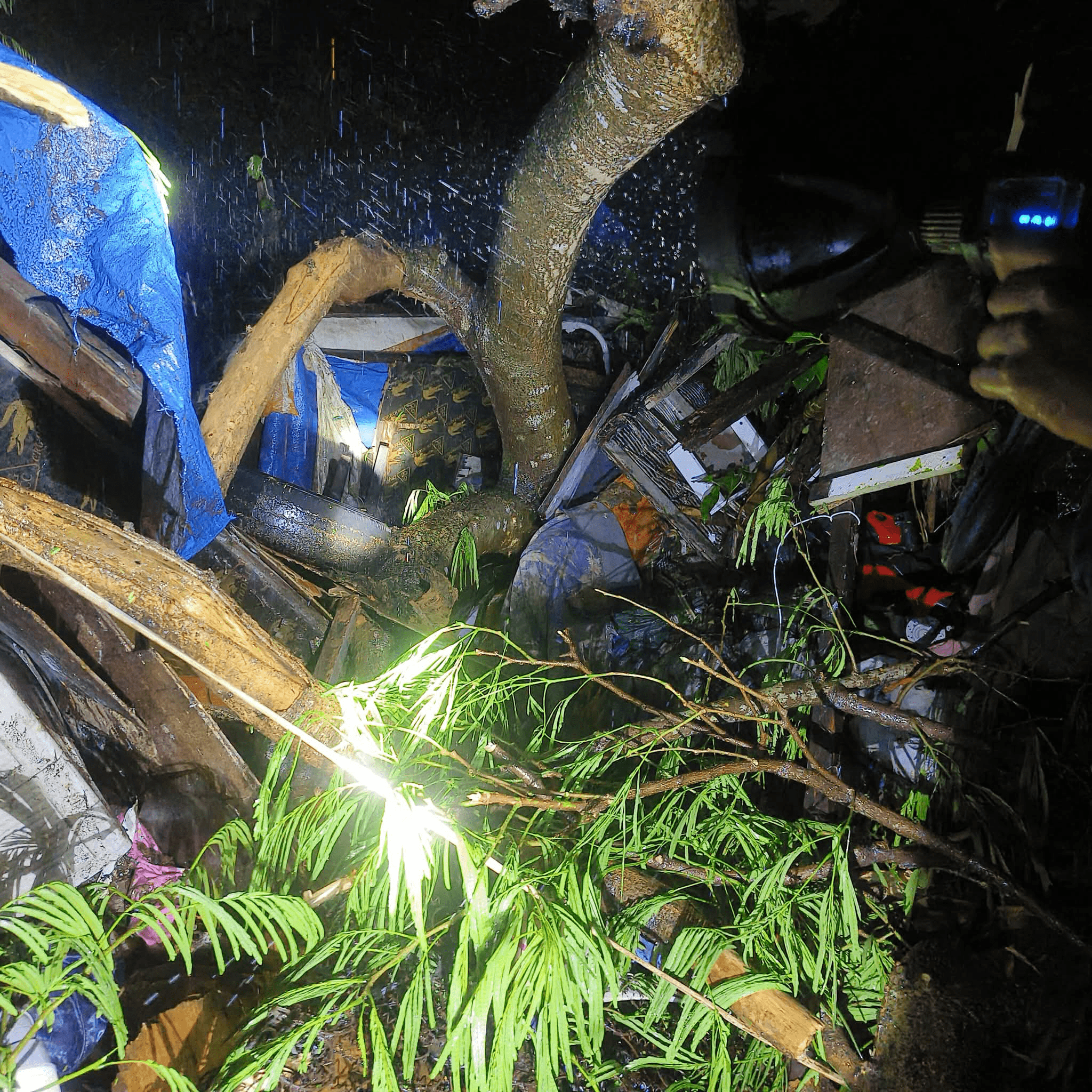

The present administration has also presided over the erosion of media freedom, most notably and, most recently, the shutdown of the country’s largest broadcasting network, ABS-CBN.

But despite such backpedaling from the government, this does not mean that the prospects of a public broadcasting system are already dead. As proven by media’s coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, Arao noted, a people-centered and a media organization devoid of commercial interests may now be essential.

“With the necessary public pressure, it can be done whether under this administration or the next. It is just a matter of articulating well the need for government media to exercise editorial independence,” he said. ●