Content warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual harassment, coercion, and discriminatory behavior.

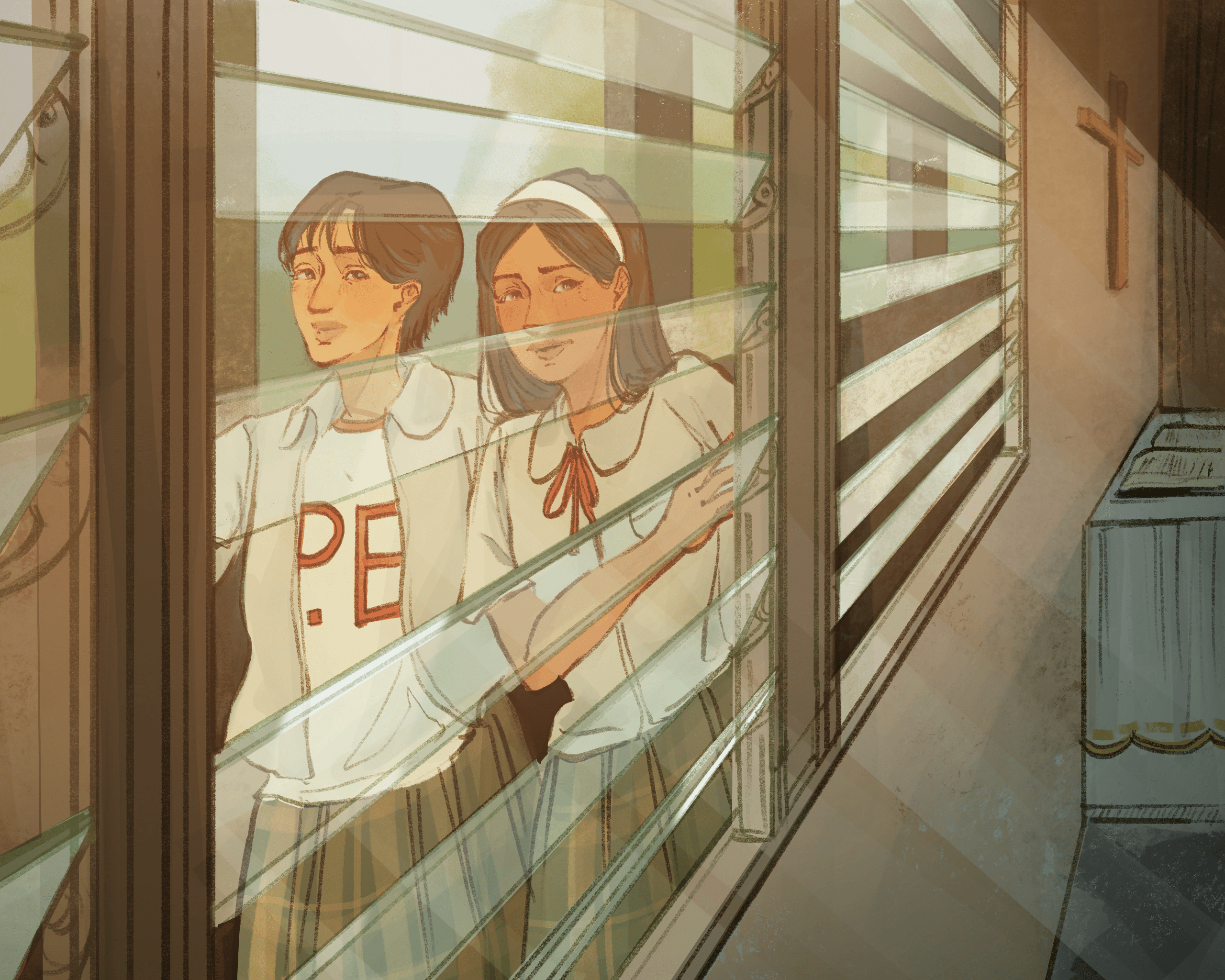

Entering third year in mechanical engineering, where classes were largely regarded as “terror subjects” in their program, Avery* decided it was time to find a support structure through a home organization—and they saw no better option than UP Gears and Pinions (GPs).

Pragmatically, GPs offered extensive academic resources and connections. More significantly, however, it promised a sense of belonging crucial for students without a solid community in their department.

“What I think is the most seductive is the camaraderie they promise. They like to differentiate themselves from other orgs in the sense that they're more of a family than anything,” Avery said in an interview.

But that facade quickly crumbled for Avery, who witnessed systemic misconduct, harassment, and coercive practices within the organization, leading them to defer their application near the end of the first semester of the previous academic year.

Time has not healed Avery’s wounds, especially since the accountability and reform Avery demanded from the organization have not yet been heeded despite filing two separate reports to their College Disciplinary Committee (CDC) and the Office of Anti-Sexual Harassment (OASH) within the last nine months.

‘Camaraderie’

As with many organizations in UP Diliman, GPs’s application process includes a signature sheet or sig sheet for applicants to get to know members. Each applicant is partnered with a member, called their buddy, to guide them.

As early as the getting-to-know portion, the sig sheet already contained inappropriate and intrusive prompts like “The furthest I have gone sexually is,” “My secret fetish is,” “Virgin pa ba si buddy? Bakit? E ako ba,” and “Mahilig ba ang buddy ko sa porn? Anong type?”

Members supposedly reminded their applicant buddies regularly that answering was completely optional—something that the current GPs executive committee argued in its response letter to the CDC complaint.

Copies of the CDC and OASH complaints, GPs’s subsequent response, and supporting evidence were reviewed by the Collegian with the permission of a source close to the case.

GPs did not consider these questions inappropriate as they “merely provide a platform that will enable the parties involved to have a healthy avenue for discussion,” as stated in their response. Nonetheless, the 2017 Anti-Sexual Harassment (ASH) Code identifies inquiries or comments about a person’s sex life as a light offense.

Avery and other applicants also deemed it especially concerning that minors in their app batch were exposed to such a culture. In one instance, there was a minor who was paired up with a 22 or 23-year-old member.

“It was very weird to me considering na yung section na yun is a getting-to-know section. Tapos, hindi mo pa masyado kilala yung buddy mo, and you have to answer those na,” said Alex*, one of three other anonymous witnesses in the complaints, in an interview with the Collegian.

‘Choice’

Beyond the getting-to-know portion, the sig sheet really hinges on the actual completion of tasks. Applicants must obtain two signatures from every member of GPs by fulfilling tasks decided by each member.

Some members had tasks requiring applicants to post videos of themselves performing demeaning or embarrassing tasks.

Avery, for one, was tasked to record themself screaming in public and post it on a dummy Facebook account but was eventually told to post it on their main account to receive the signature from the member largely regarded as a terror member.

But some of the other tasks that were required to be posted only in the private Facebook group between members and applicants typified humiliation in a different way.

For one, a task involved an applicant videotaping themself completely nude, save for another applicant obstructing their genitals. Another involved an applicant photographing themself nude but with a toy car covering their genitals.

A clip of one task where an applicant pretended to pee on another co-applicant, while making inappropriate sounds in the background, was even shown in a promotional video for the org’s subsequent application season, though supposedly with their consent, per GPs’s response.

None of the tasks involved full nudity, a technicality that GPs held onto in its response letter. “Simply showing one’s body, especially in a non-sexual context and without any explicit sexual elements, cannot reasonably be construed as sexual advances,” it said in its response.

GPs also asserted that applicants performed these tasks entirely out of their own volition, as the members prepared other less explicit tasks.

But more humiliating and explicit tasks garnered a larger reaction from the members—a response crucial to applicants, since the lack of “remarkable tasks” could be a basis for rejection, said Avery.

Tasks or activities with sexual undertones should not be included in org activities at all, especially for application processes, where there are no strictly objective criteria for an applicant to be accepted, said Janet De Leon, University Extension Specialist I under OASH, in an interview with the Collegian.

While doing these tasks, there was also an added layer of intimidation, Avery said, as some members would rip up sig sheets.

GPs said in their response that such an act should be justified by the member, and they could face sanctions for failing to do so. But Avery said that any such reasoning was never disclosed to the apps, so they all operated under the assumption that their sig sheet could be torn apart at any given point.

One member also introduced a “wheel of names” mechanism, where a random applicant would be permanently barred from receiving that member’s signature if their group failed a task. Since acceptance to the org required obtaining signatures from all members, this effectively meant that the selected applicant would be rejected.

Culture

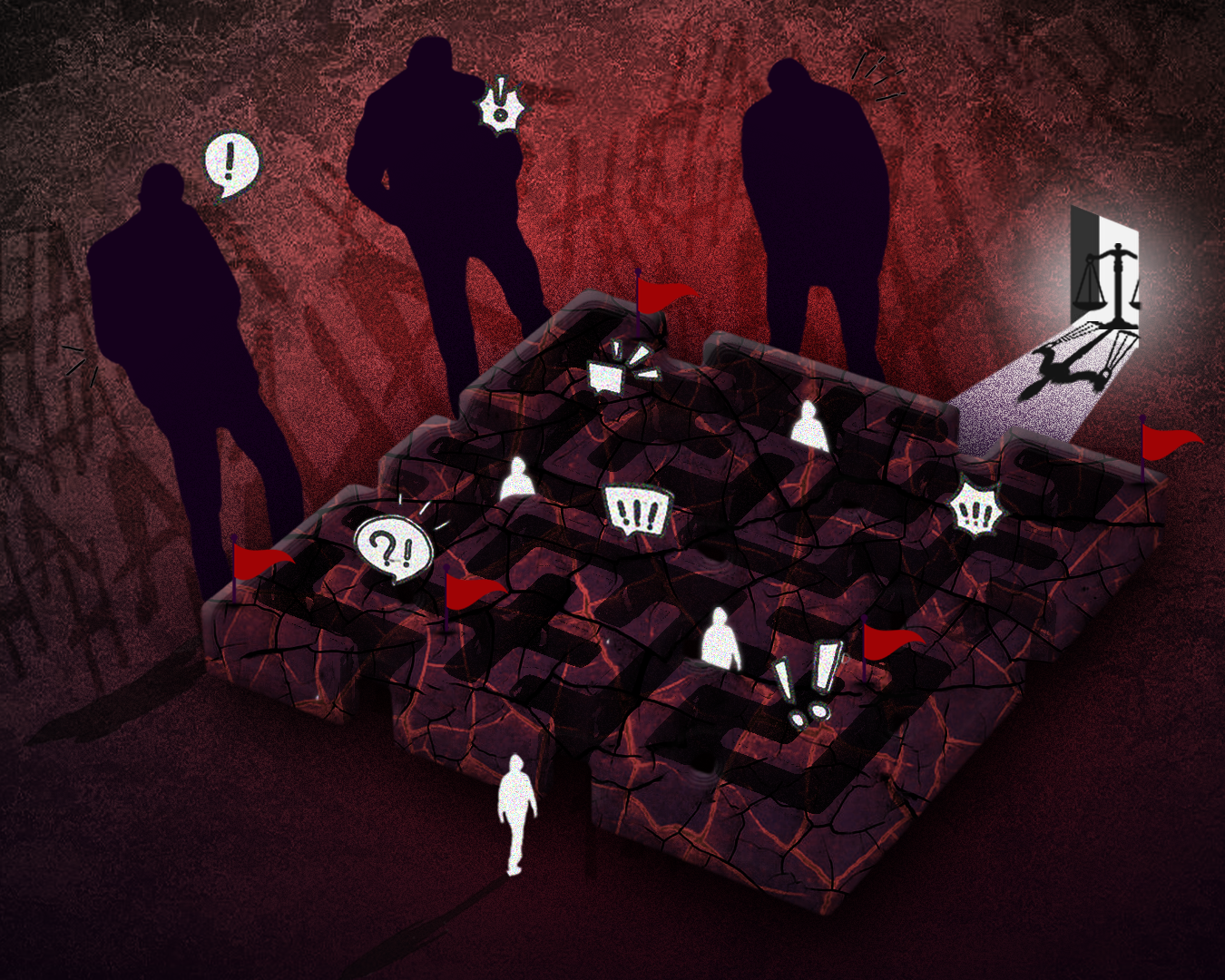

Unaware of the inner workings of the organization, applicants could feel pressured to conform to whatever the application process entails, reinforced by the culture they perceive within the organization.

Such a culture may be seen in the org’s sig sheet at the time, which included anonymous descriptions of all the members from other members.

But interspersed within the sincerity of some of the messages were descriptors like “pwedeng bumili dito ng damo,” “homophobe,” and “nagsasabi ng n-word” that seemed to normalize drug selling and trivialize discrimination.

GPs has a history of making offensive remarks against the LGBTQ+ community, one that they acknowledged and promised to correct in a statement released during Pride Month in 2020.

Yet during Avery’s application, they cited an instance where an applicant and their buddy posted a photo of them hugging each other shirtless in bed—“pretending to be gay,” said Avery—which garnered laughters from some members.

“Using someone's sexual orientation as the punchline of a joke reduces their identity to something laughable or abnormal, perpetuating stigma,” said Avery, who is bisexual themself.

Though screenshots of their conversations showed that some of the executive committee members agreed with Avery that it was offensive, both the current and former executive committees reneged on this in their response letter. “The post in question was a display of friendship and camaraderie between the applicant and a member. … It was not intended to demean or trivialize LGBTQ+ experiences in any way,” it read.

At that point in their application process, Avery complained to the executive committee about the post.

Applicants and members had avenues to express complaints within the organization like grievance forms and personally messaging or approaching a member of the executive committee. But Avery felt the org lacked in enacting reforms.

Of Avery’s demands to which the executive committee agreed, the executive committee had the offending applicant apologize verbally, but they did not supply a signed apology nor issue a memo to the applicants explaining that Avery was deferring their application because of the culmination of their unpleasant experiences.

Avery expressed that the latter condition was necessary since some tasks required the cooperation of the whole app batch or groups of applicants of which they were part.

Notably, the executive committee did not hold a gender sensitivity training either, despite Avery’s request.

At this point, effecting reform internally had reached a dead end, leaving only external and authoritative bodies like the chancellor or college dean with the ability to properly implement or, at least, guide changes.

For one, attending relevant activities like gender sensitivity trainings is one of the alternative correct measures that may be imposed upon an organization if formally charged with sexual harassment, per the ASH Code.

Avery tried to move past the ordeal after they deferred their application. But on one particularly difficult day—which soured further after some GPs members taunted them while bragging about ripping some application forms—they realized that no reforms had been made, and they finally decided to file a report to OASH.

Challenging Complaint

Avery expected their last two years in their degree program to be grueling ones, but they did not expect the additional weight of the long and bureaucratic process of the system they chose to have faith in.

Under a recommendation by the ASH Council after its hearing, GPs’s application process was temporarily suspended, as confirmed by the organization in an email exchange with the Collegian.

This was as much as GPs told the Collegian, citing confidentiality as the reason they could not discuss elements of the case itself.

During the period of the app process suspension, Alex and Avery said that students generally thought that the measure was imposed because a student drew a penis next to the org’s logo on a window panel.

Neither Avery nor any of the other anonymous witnesses could have clarified the matter since the ASH Code has a confidentiality clause. Under this clause, parties, including complainants, cannot publicize a case lest they face disciplinary action, even if their case has already been trapped in limbo for an extended period of time.

The suspension was eventually lifted after GPs laid down their proposed revised application process to OASH. Some of the amendments included codifying guidelines for the application process, clarifying expectations for member behavior and conduct, and standardizing internal review processes.

GPs also said that the OASH case was dismissed and attached a certificate of no pending case from the office, issued Jan. 13.

But in fact, the case has not been dismissed, as confirmed by one of the anonymous witnesses, and it has already been elevated to the chancellor, who can either dismiss it or issue a formal charge. This implies that the preliminary investigation by the ASH Council found probable cause to pursue the sexual harassment charge.

Organizations cannot be tagged with a pending case, since the ASH Code limits accountability only to individuals. This technicality is why Avery was asked to reframe their OASH report to address GP’s executive committee during their application process, two months after submitting their initial report.

Now, nearing 10 months from Avery’s initial filing of the OASH complaint, the case is facing yet another obstruction: It has been sitting at the chancellor’s desk for nearly two months.

The same story goes for all OASH cases involving student organizations awaiting either a formal charge or dismissal from Diliman’s head office, as confirmed by OASH in its interview with the Collegian.

Closing In

Though the results of the sexual harassment complaint are still uncertain, the college-level org misconduct case could be nearing its close.

College of Engineering Dean Maria Antonia Tanchuling recently affirmed the findings of the CDC that the org had violated the Student Code provisions on harm to persons and misconduct, and the Anti-Hazing Law.

Per the dean’s decision—a copy of which was again reviewed by the Collegian with the permission of a source close to the case—GPs’ accreditation as a student organization will be suspended for one semester. It will also have to issue an apology letter to the complainant and a reflection letter to the dean detailing their refined plan for the application process.

The organization may still file an appeal, pursuant to Section V.3.6.13 of the 2012 UP Diliman Code of Student Conduct.

But notably, the dean did not adopt CDC’s recommendation that the organization issue a public statement apologizing for harm caused by their application process.

Should the dean’s decision finally come into effect, this will at least be one door closed for the victims, though one that hardly signifies the end of the process for Avery, as the OASH complaint is yet to be concluded and GPs itself has yet to face sanctions.

"I will not let my pain go down merely as collateral,” Avery said. “This is not just about seeking justice for myself but ensuring that no one else has to endure the same pain, exploitation, and humiliation.” ●

*Not their real names. They asked the Collegian to conceal their identities due to the sensitive nature of the article.

To report incidents of sexual harassment, you may fill up this incident form from OASH, or contact the office through their email at oash.upd@up.edu.ph or Facebook at www.facebook.com/updilimanoash for further assistance.

First published in the June 19, 2025 print issue of the Collegian.