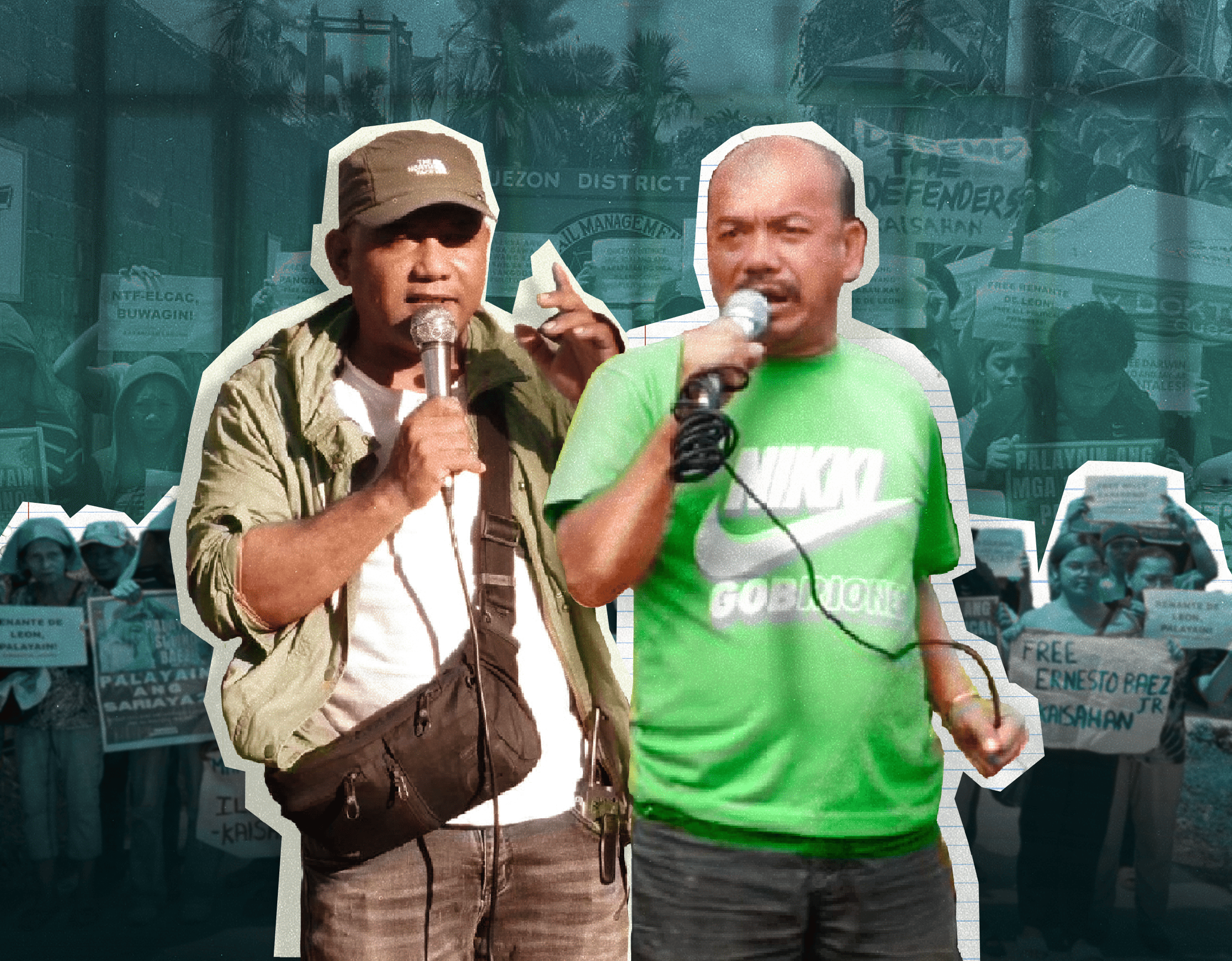

Lucena rarely hears the noise of protest. Unlike big cities in the Metro, its streets rarely witness shouts and stomps from protesters making their calls known. But on June 16, a group of Batangueños picketed on Perez Park to call for the freedom of peasant advocates Erlindo “Lino” Baez and Wilfredo “Willy” Capareño.

Baez and Capareño were to take the stand that day. Although both have been at the forefront of activism for the longest time in Batangas, trumped-up charges caused them to be locked up in Quezon.

The two have fought for land, wage, and housing rights together with various farmers and workers in the region. True to their nature, they were arrested on Oct. 6, 2021 in Sariaya, Quezon, while preparing for a consultation with farmers.

The roots of their imprisonment trace back to a broader pattern of state repression in the region. Baez was a victim of the dragnet operations which resulted in the Bloody Sunday Massacre on March 7, 2021, after state forces planted weapons in his home while he was away. He was acquitted of a similar charge in October 2021 by the Tanauan Regional Trial Court (RTC).

But, authorities once again put weapons in their homes in 2021 while they were arrested, which became the basis of their current cases now being heard in the Lucena RTC.

“Ang naratibo ng mga iligal na pag-aresto at pagsampa ng mga gawa-gawang kaso laban sa mga aktibista ay litaw na manipestasyon ng nagpapatuloy na kultura ng pasismo ng estado, [na] patuloy na pinaiiral ng kasalukuyang rehimeng US-Marcos, which are often weaponized recently against activists, particularly in the Southern Tagalog region,” Tanggol Batangan spokesperson Hailey Pecayo said.

Cases of illegal possession of firearms, ammunition, and explosives are non-bailable offenses. For four years, both Baez and Capareño have endured hardships inside the prison, which are exemplified by health problems. This sordid state of political prisoners in Quezon, however, is not theirs alone.

Inhumane Treatment

A press release by Kapatid on June 26 detailed cases of torture within Pagbilao District Jail in Quezon. “Nine political prisoners are prohibited from speaking to one another, padlocked by 4 p.m., and often go without supper. The jail floods during heavy rain, lacks sanitation, imposes a cashless system with steep GCash fees, and charges high fees for cooking,” the report said.

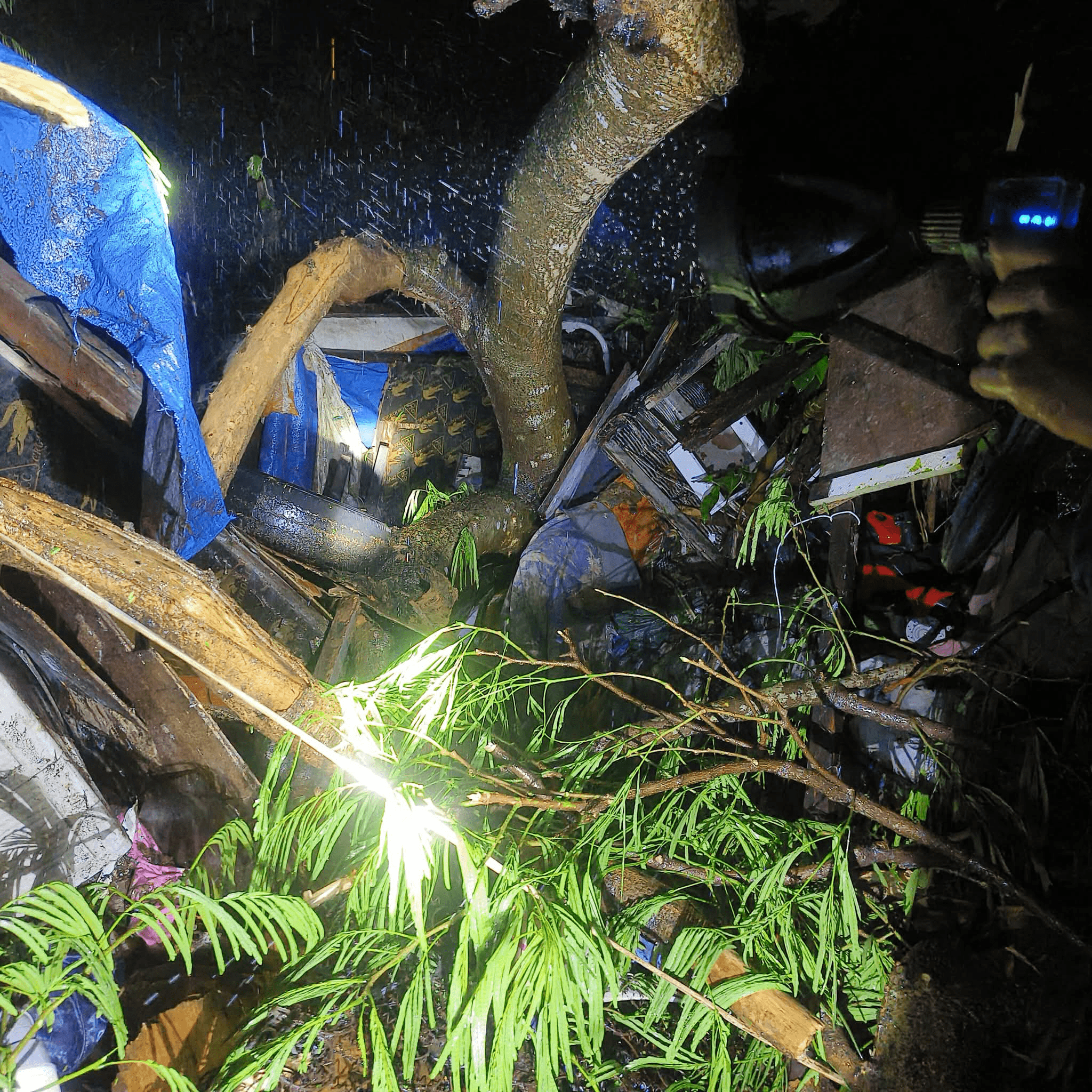

These jails are often poorly constructed, with little to no renovations. For instance, when Typhoon Aghon wreaked havoc in the province, it severely affected the political prisoners in Quezon District Jail, with their properties, including hygiene items and clothes, being washed away.

For Tanggol Quezon spokesperson Paul Tagle, the state of political prisoners in Quezon, where access to even basic necessities is limited, reflects the rest of the region. In Quezon District Jail, access to water is so limited that prisoners are often pushed to buy or fetch dirty water.

In these prisons, signs are hung outside their cells with either “CTG” (communist terrorist group) or “VEO” (violent extremist offenders) written on them. Aside from inmates being instructed not to speak to these tagged prisoners, visits from families and lawyers are also repeatedly delayed, further prohibiting the political prisoners from having contact, Kapatid explained.

Cases like this are very apparent in the province. Former desaparecido Rowena Dasig was tagged as a “high-risk” person deprived of liberty during her imprisonment in Lucena. This prompted an 8-month communication delay between Dasig and her paralegals.

Such dire circumstances are also what environmental defender Miguela Peniero, who was originally imprisoned with Dasig, is currently experiencing in Lucena City District Jail. “Pinaghihigpitan siya doon at hindi pinapahintulutan na makausap ang kanyang ibang mga kapamilya. Hindi rin pinapapasok madalas ang ibang mga padalang pagkain sa kanya,” Tagle told the Collegian.

In fact, Paul Tagle and fellow activist Fritz Labiano were charged with terrorism financing charges for helping Dasig and Peniero during a prison visit. They were only cleared of these charges after a Batangas court deemed the state’s evidence as insufficient.

Outside Their Cells

The state’s treatment of these prisoners beyond the cell walls is no different. Terror-tagging continues to be rampant through extensive smear campaigns.

Current political prisoner in Quezon, Gavino Panganiban, is a trade union leader and the director for campaigns of Kilusang Mayo Uno’s regional formation in Southern Tagalog. When he was arrested in October 2024, he was suddenly categorized by the Philippine Army in a press release as a high-ranking “NPA terrorist leader.”

Another case is Darwin Palo, a farmer from Lopez, Quezon, who was arrested on March 27 after being accused of being a collector for the New People’s Army.

An investigation launched by Tanggol Quezon revealed that Palo and a companion were just traveling to Bulacan for work when the police and military apprehended them at the Lucena Grand Terminal.

“The victims recounted that they were arrested without being shown warrants or being read their Miranda Rights, which supposedly state their rights as accused individuals,” Ang Bayan reported.

In another press release by the military, Palo suddenly had the alias “Queen” and became an NPA leader. The farmer was apparently caught with a cache containing an “M16 rifle, two anti-personnel mines, four magazines for M16 with 67 rounds of ammunition, [and numerous other firearms].”

These press releases are often haunted by numerous typographical errors and even wrong acronyms.

Another farmer from Lopez, Rico Edrinal, was arrested on April 6 and is now a political detainee in Quezon. His niece, Reazel Noriesta, was just recently harassed by soldiers after they visited her house in Atimonan, Quezon on June 17.

In these visits, these soldiers with guns often push the rhetoric of helping families to free their detained relative in exchange for the relative’s “surrender.”

“Hindi lang si Ate Reazel ang binubulabog at tinatakot ng mga militar pati na rin ang kanyang ibang pamilya. Yung ganitong taktika ng estado, partikular sa mga militar, ay matagal na nilang ginagawa, pinupuntahan [sila] pagtakatapos ay [kukumbinsihin na pasukuin], kapag tinanggihan ay tinatakot, dinadahas at pinagbantaan ang buhay,” Tagle added.

The Fight for Freedom

The political prisoners’ poor condition inside and outside their cells makes the push for their freedom stronger and more urgent. Southern Tagalog human rights groups played an active role during United Nations special rapporteur Irene Khan’s visit to assess the country’s human rights state last year.

One of the groups, Defend Southern Tagalog, welcomed Khan’s call for the government to review and amend the Anti Terrorism Act of 2020 which was launched during former President Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency.

Defend Southern Tagalog spokesperson Charmane Maranan also pushed for the review of Administrative Order 35, which aims to build an Inter-Agency Committee on Extra-Legal Killings, Enforced Disappearances, Torture, and Other Grave Violations of the Right to Life, Liberty and Security of Persons.

“Dito sa Southern Tagalog matatandaan natin na yung AO 35 task force ang inatasan na mag-imbestiga sa mga kaso ng Bloody Sunday. Apat na taon na ang nakakalipas, wala pa ring napapanagot ang AO 35,” Maranan said.

The leader of this task force is none other than Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla, who is now eyeing to become the next ombudsman.

“Kaya mariin dapat talaga nating ipinapanawagan na palayain ang lahat ng bilanggong pulitikal, at igalang ang kanilang karapatang pantao sa loob man o labas ng bilangguan,” Tagle said. ●