There are three turtles in the pond in Palma Hall. I used to make it a habit to try and see them every day in school, kind of like a sibylline ritual where, if the turtles surfaced from the murky waters for me, I would have a great day ahead. Call it a self-fulfilling prophecy or whatever, but I subscribed to this superstition closely back when there were face-to-face classes and the world had gone far less haywire.

From across the pond are benches where a white cat with different colored eyes would usually hang out. In the nearby hallway in front of the History Department is where Daisy, another famous Palma Hall cat, is almost certain to be lounging about. Running late for my next class is no excuse for me to stop and try to give these cats a quick pat on the head or a stroke, depending on what they will consent to that day.

Greeting the guards stationed in the buildings’ entrances was also an integral part of my daily routine back then. A return greeting from them, often with an accompanying genuine smile unobstructed by a face mask, was an instant pick-me-up, except, I suppose, when it came from the guard in the Institute of Chemistry, as it probably meant I could not enter the building because I had forgotten my ID.

“But if you close your eyes, does it almost feel like nothing changed at all,” goes the chorus of one of Bastille’s annoyingly catchy songs. These days cannot help but resonate with the song’s sentiments. UP for me exists in brief flashes of episodic memories of some parts of my college experience, which was unceremoniously cut short by the pandemic. A throwback photo or an artifact from the before era like an ID lanyard will occasionally trigger a recollection of some of these memories.

Recently, I have realized that I am actually starting to forget the minutiae of studying in UP: my favorite kiosks and what snacks to order from them, the cost of one lemonade with Yakult, where the nearest comfort room or water fountain is to every classroom (why they come paired, I would rather not think about), even the distinct way we tell our campus jeeps to stop. It even took me some time to remember the cost of one discounted Ikot ride.

Like countless others before and after me, I entered the university in 2018, full of fear and hope for the future ahead. At the back of my mind was the belief that our late teens and early 20s are for making mistakes and experiencing, well, life. Then, and perhaps until now, I had this notion that UP is the best place in the world to both lose and find myself along the way of making friends and bad decisions, maybe skipping some classes, joining orgs, going on a date—being a stereotypical college kid, if there ever is one.

But the virus came and I, like thousands of fellow students, was unceremoniously booted back to my home province and forced to pretend that, to borrow words from the writer Carina Chocano, I am receiving a real education so that schools can pretend they are providing one. Much has already been written about how mentally taxing and ineffective online classes are, so I would rather not go down that rabbit hole of rants.

This column, I suppose, is part-dirge and part-celebration of the experiences I had during my two-year stay in UP. I miss the campus, the places to eat in, the public art installations we, in retrospect, took for granted. I even miss the 164 acacia trees lining the Academic Oval and the shade their canopy provided during the walks that ranged from recreational to romantic. Above all, I miss the people—the casual encounters with friends in between classes and the quick catch-ups during random run-ins. For the batch of students who entered the university without ever entering its premises and experiencing what we experienced, I seriously hope you get a taste of all this someday.

The university was supposed to be a place of hopes and dreams, of freedom to lose and find and maybe lose one’s self again and again. Eraserheads’ “Minsan”—which I remember listening to on an Ikot ride on my first day as a UP student—begins with the famous line “minsan sa may Kalayaan”—the capital K referring to the dormitory for freshmen. I think it can also be in lowercase, for it is here—or there, rather—where many of us get the first taste of true freedom to choose among vastly different ideologies and philosophies in life.

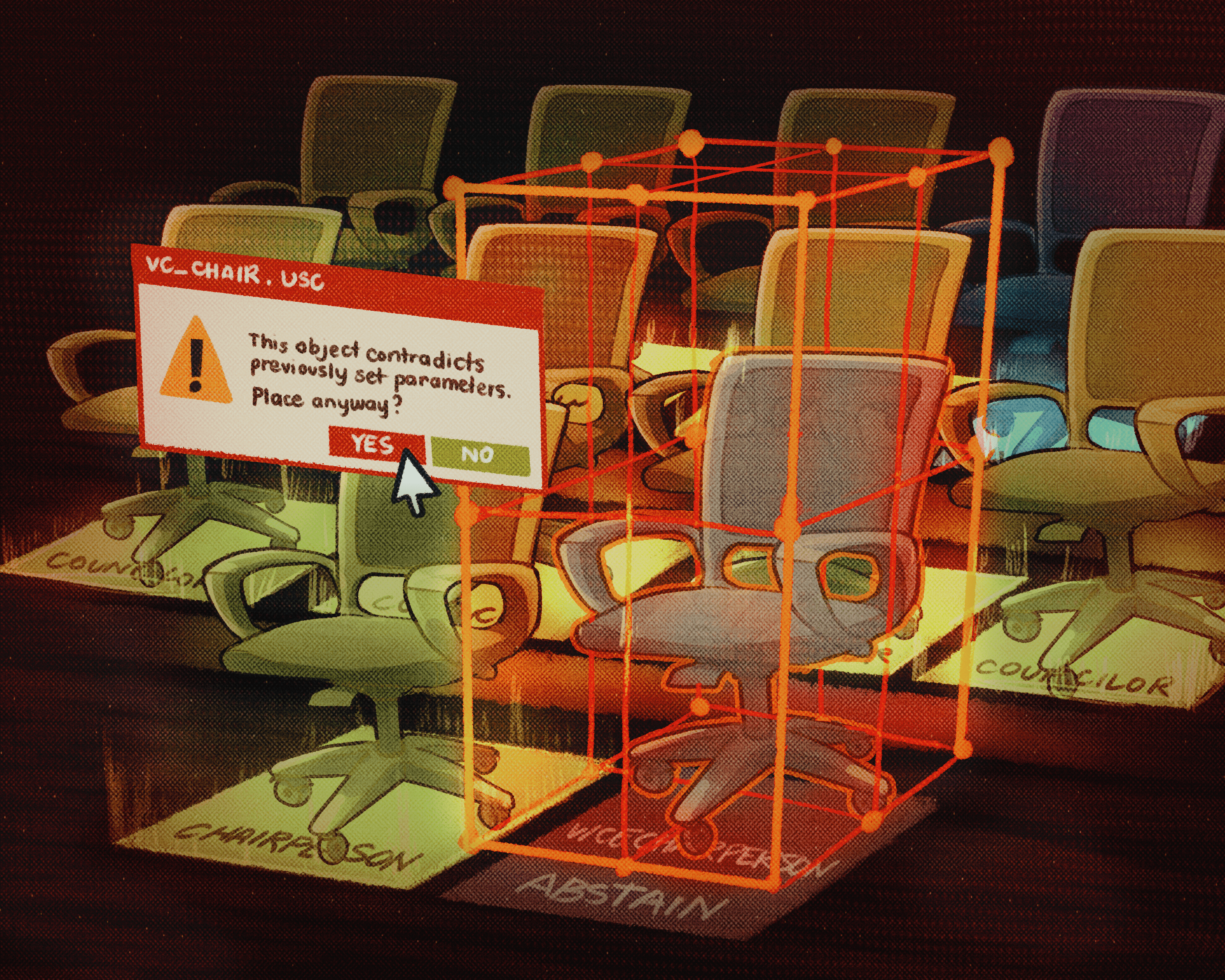

My CRS account now bears the “graduating” tag—a somewhat uncomfortable reminder that I am already close to leaving this place. “Place,” now, of course, feels more temporal than spatial. There is this unmistakable sense that an integral chapter in my life, in our lives, will end forever unfinished.

I used to think that we live in the future tense during this pandemic, in the plans we vow to ourselves we will do after all this is over. Recently, I came across the concept of the irrealis moods in grammar. It turns out there are events that cannot be covered by the indicative mood in past, present, and future tenses—hence the need for sentences that refer to our hopes and dreams, events that are unreal, unlikely, and downright impossible. “I would like to go back and see the sunflowers bloom for me,” for one, is an example of a sentence in the irrealis mood. And now, it seems, so is the phrase “when all this is over.” ●

*Taken from Bastille’s song.