By DABET CASTAÑEDA

Hacienda Lusita, Tarlac (125 km. north of Manila)—The small dikes that separate the parcels of farmland are all wet and muddy. The newly planted rice stalks are bent in different directions. The stalks of string beans are jumbled alongside a forest of tall grass while a stretch of kamoteng kahoy (cassava), miniature eggplants, and green chili are scattered just beside a hut.

It is only the second day of the planting season for 71-year old Perfecto Versola, or Mang Pering, and his family. It coincided with the second day of Typhoon Egay, the strongest storm to hit the country so far this year, and the farm workers are all soaked up, including Mang Pering, who has been suffering from asthma for the last two days. Even his grandchildren who just came from school that day joined the farm hands to rebuild the small dikes that have eroded while the old man’s polio-stricken daughter helped out in the weeding process.

The Versola family started to cultivate 2.2 hectares of land here in Barangay Balete March this year planting vegetables for a start. It is the first time since more than five decades ago that farm workers in Hacienda Luisita are able to produce food crops for their own consumption.

“Nu’ng araw, kahit kulitis hindi namin pwedeng pitasin,” Mang Pering said. “Hindi rin kami pwedeng magtanim kahit sa loob ng bakuran namin.”

Sugarland

It was in 1957 that the Cojuangco family of Tarlac, clan of former President Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino, acquired the 6,000-hectare sugar producing hacienda from its Spanish owners, the Compania General de Tabacos de Filipinas (Tabacalera), using government funds.

In 1988, during Cojuangco-Aquino's term, the hacienda was placed under the government’s agrarian reform program through a new scheme known as the Stock Distribution Option (SDO). This paved the way for the Cojuangcos to convert the 6,000-hectare hacienda to a 4,000-hectare family-owned corporation (the Hacienda Luisita, Inc. or HLI), and give farm workers shares of stocks instead of actual land parcels.

The SDO scheme combined with the mechanization of the sugar farm process has led to decline of the farm workers’ basic pay which, since the early 1900s, has dwindled to a suffocating P9.50 a day and has resulted in the retrenchment of hundreds of farm workers.

To Die For

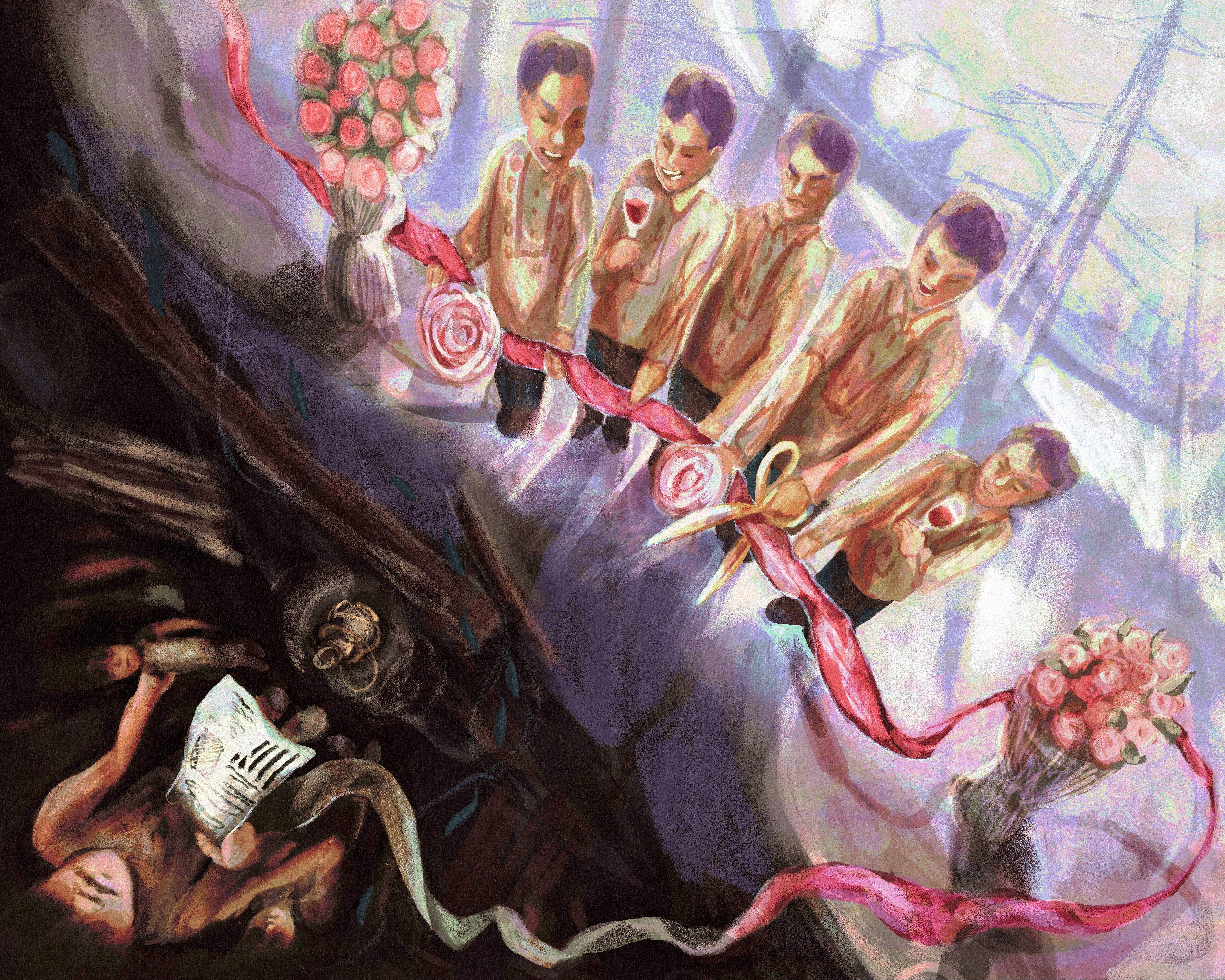

In 2004, HLI farm workers and mill workers of the Central Azucarera de Tarlac (CAT), also owned and operated by the Cojuangcos, staged a simultaneous strike to demand the reinstatement of union leaders and members who were not even paid their separation pay, the revocation of the SDO, and to pave the way for actual land distribution to farm worker beneficiaries.

The strike caught national and international attention when, on November 16, 2004, or exactly 10 days into the strike, seven farm workers lay dead in front of the gates of the CAT sugar mill after state security agents and snipers, who were suspected to be members of the Cojuangcos’ private army, opened fire at the strikers in what is now known as the Hacienda Luisita Massacre.

Mang Pering and his family were there during the massacre. His daughter, Flor, was hit at the back while one of his sons was hit on the buttocks.

After the massacre, the farm workers painstakingly rebuilt the picket line. Harassments and intimidation continued, though, resulting in the deaths of their union officers—CAT president Ric Ramos and HLI Director Tirso Cruz—and staunch supporters—massacre witness Marcelino Beltran, Tarlac Councilor Abel Ladera, Fr. William Tadena, and Bishop Alberto Ramento among others.

When the strike was finally lifted in October, scores of families had to leave the hacienda fearing for their lives. That included Flor’s family as she has been a target of a series of black propaganda and continued harassment for being an active member of the farm workers’ union.

Distribute the Land

On September 30, 2005, the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) recommended the revocation of the SDO after a thorough investigation of its implementation in HLI and its severe implications on the lives of farm workers.

In December 2005, the Presidential Agrarian Reform Committee (PARC) decided with finality the revocation of the SDO in HLI and ordered the DAR to distribute parcels of lands of Hacienda Luisita to its rightful owners—the farm workers.

The Cojuangcos, however, asked the Supreme Court (SC) for a Temporary Restraining Order (TRO). The request was granted after the Cojuangcos shelled out a P5 million bond.

Starting All Over Again

It took almost two years for Flor and her family to return to their home in Barangay Balete, one of 11 villages comprising the hacienda.

“Mahirap, parang nagsisimula ka ulit,” Flor told a reporter in an exclusive interview with Bulatlat, right in the middle of the 2.2-hectare sugar land which has been converted to a rice and vegetable farm.

The farm workers in the hacienda are literally starting from scratch since the strike was lifted more than two years ago, HLI Union President Boyet Galang said in a separate interview. Galang has had to flee the hacienda, too, since he has been a long-time target for assassination. He now stands as the president of the Ugnayan ng mga Manggagawa sa Asyenda (UMA or Association of Hacienda Workers), a national network of farm workers.

Using funds provided by management as part of the final agreement ending the strike, Galang said their union has built a cooperative aimed at helping the farm workers and their families to start planting rice and vegetables instead of sugarcane. Since two years ago, almost half of the hacienda (or an estimate of 2,000 hectares) has been converted to rice and vegetable farms.

The union cooperative provided for the construction of deep wells for irrigation and the acquisition of farm inputs. The cooperative, Galang said, is also starting to acquire farm machineries such as kuliglig (hand tractor) and thresher.

Rewarding

Planting vegetables has been rewarding, Flor said. She sells them to neighbors and earn at least P500 in three days, a far cry from their P9.50 daily pay from HLI years ago. “Basta matyaga ka lang, kikita ka na, may libreng ulam ka pa. Kasi ‘yung tanim namin, ‘yun na din ang pagkain namin,” Flor said.

But more than the monetary compensation, what is more redeeming, Flor said, is the actual cultivation of the land that is rightfully theirs. ●

Published in print in the Collegian’s August 28, 2007 issue.