With the prospect of a prolonged economic recovery due to the imposition of strict lockdowns anew, groups have warned that the government should do away with its short-term and small stimulus package and consider enacting a relief measure that would also address the long-term effects of the pandemic.

Bayanihan 1 and 2, though the largest stimulus packages yet in the country’s history, have still been criticized for being inadequate to people’s needs during the pandemic. Enacted in March 2020, Bayanihan 1 only allocated P217 billion for direct aid, while Bayanihan 2, passed six months later, programmed a smaller P140 billion for various types of aid.

“Direct emergency cash aid to the poor is the fastest and most effective way to help them,” IBON Executive Director Sonny Africa said in an email to the Collegian. Bayanihan 1 implemented the Social Amelioration Program (SAP), which doled out a P5,000 to P8,000 cash aid to the poorest families around the country in two tranches.

Even the World Bank has noticed the country’s shortchanged economic stimulus. In its April 2021 report, the WB noted that the government “underspent” on its stimulus packages due to “weak implementation.”

Combining all the country’s pandemic-related spending, the government only spent P11,664 per Filipino, according to the Asian Development Bank. This is one of the lowest relief per capita in the Southeast Asian region (see sidebar 1).

The Bayanihan packages also failed to address the continued contraction in the country’s agricultural sector. Despite last year’s direct cash aid to low-income farmers, this failed to spur the recovery of the sector, particularly livestock and poultry farmers.

While international finance organizations, and local think-tanks, including the state-run Philippine Institute for Development Studies, advocate for another round of stimulus and relief package, the costs for that and how to pay for it vary (see sidebar 2).

‘Bigger, Bolder’ Package

Progressive lawmakers, for their part, have proposed a P1.5 trillion stimulus package. Filed last September 2020, SHIELD Bill sought to address the present economic malaise while investing in building a resilient health care system, economy, and national industry.

The Makabayan bloc’s plan is also similar to that of progressive think-tank IBON Foundation’s package, with a nearly identical price tag, which they proposed last January. Both proposals aim to address the financial distress of low-income families and struggling small businesses in the short-term.

IBON’s plan pitched a P450 billion allocation to give immediate and emergency relief for low-income families, and invest in small businesses. This forms the bulk of the P1.5 trillion economic stimulus package plan that the group put forward (see sidebar 3).

The proposed cash aid would give P10,000 worth of monthly cash aid to 18 million poor and low-income families for three months, contrary to the government’s ECQ ayuda worth only P1,000 per individual—an amount just barely equivalent to two days’ worth of minimum wage in Metro Manila, and even meager than P1,064, which is the estimated total daily expenses of a family of five. Each family can receive a maximum of P4,000.

“Ang gusto ngayon ng sektor ng maralita ay mabilisang pagbibigay ng ayuda,” said Mimi Doringo, the secretary-general of urban poor group Kadamay in a phone interview with the Collegian. “Ngayon, itong sinasabi nilang P1,000 per individual—sana nga mangyari yan per individual—ay hindi naman siya cash.”

A total of P22.9 billion was released to the local governments of the Greater Manila Area. This was earmarked from the unspent funding of Bayanihan 2 whose validity has been extended until June 30. The aid may come either in kind or cash, depending on local governments.

For Doringo, cash aid is simply more practical.

“Ang gusto natin, cash kasi iba yung pangangailangan ng bawat indibidwal, ng bawat pamilya,” she said. “Paano kung bibili ka ng gamot pero ang binigay sayo, noodles? Pwede bang i-barter yun sa botika? Yung mga nanay, kailangan ng diaper at gatas—lalong lalo na yung gatas.”

Aside from the measly aid, Doringo also emphasized that the chaotic SAP distribution last year should change. She said that Kadamay chapters have received reports of families being literally robbed since SAP distribution could end as late as 2 a.m. Requirements like IDs and a mobile number were also asked before they could claim their cash subsidies.

While the government has attempted to remedy these delays by partnering with banks and e-commerce platforms to distribute the cash aid, the Department of Social Welfare and Development was not able to finish distributing SAP’s second tranche until November 2020—four months after they began.

To do away with such documentary requirements and long queues, Africa suggested that the government make aid available to more families. In that way, implementing the SAP would be quicker as there would be less verification of who “deserves” to receive aid.

“The hurdles are there because the government is overly obsessed with scrimping on the aid they give and preventing so-called leakages—yet the situation is so bad that these should be secondary concerns,” Africa said.

Bailing the Hog Farmers

In addition to direct cash aid to low-income families, the next economic stimulus package must also help the agricultural sector that has yet to recover from calamities and livestock diseases. Food has become less affordable due to inflation, which has now reached a two-year high in the first quarter of 2021. Among the hardest hit is meat products, which as of last quarter, recorded a 20.7 percent uptick on its price, despite government-imposed price ceilings.

Last year, livestock and poultry production—which make up about one-third of the country’s agricultural production—contracted during the months when community quarantines were imposed (see sidebar 4). Their decline primarily contributed to the overall decline in the country’s agricultural production for 2020, according to compiled data from the Philippine Statistics Authority.

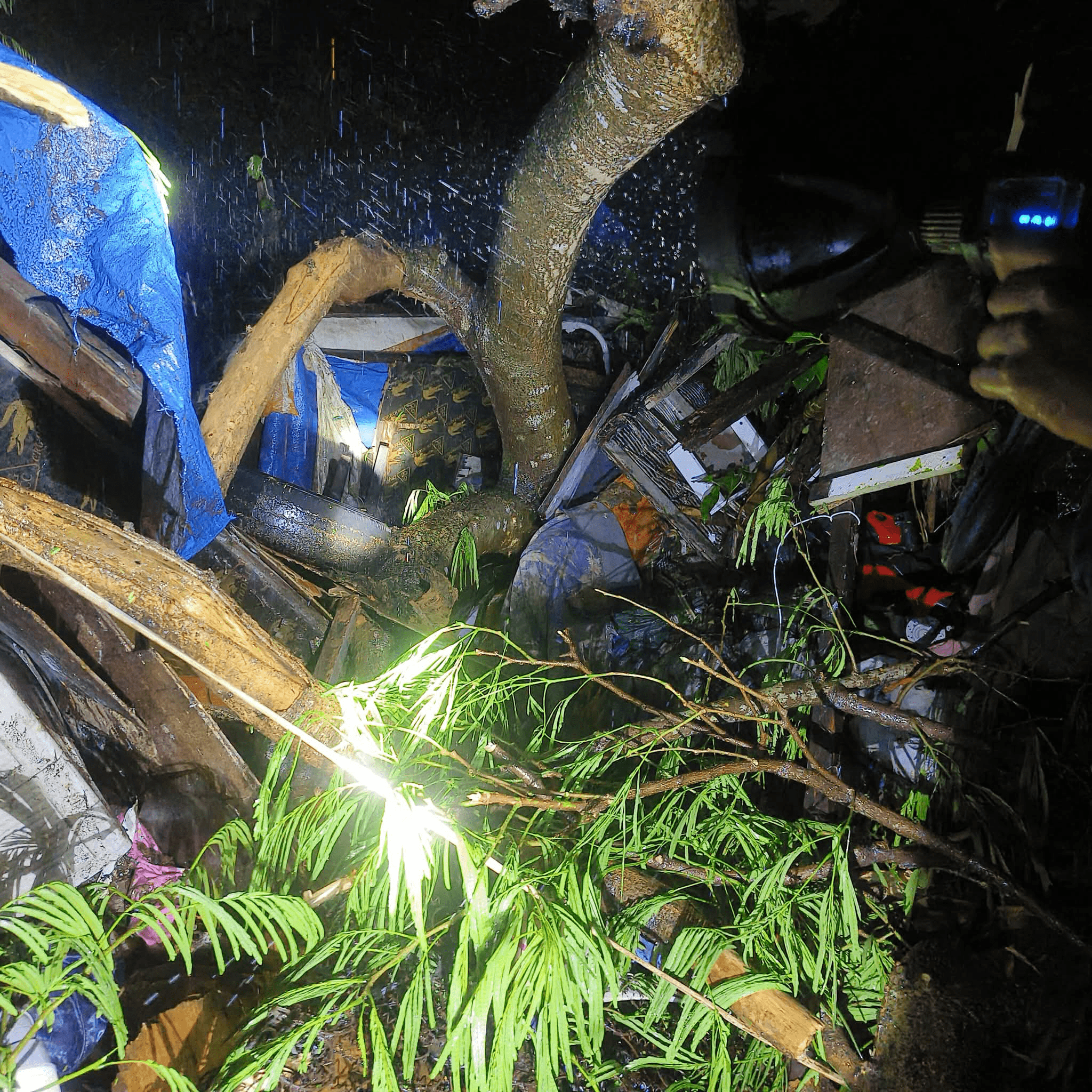

While dealing with the logistical nightmare of transporting live animals and products amid lockdowns, the hog industry is also battling the African Swine Fever (ASF) virus which has, so far, led to the culling of 435,000 pigs since the outbreak began in August 2019, according to data from the Department of Agriculture (DA).

The hog industry has been so decimated by the virus that around a quarter of the country’s hog population has died or been culled between the last quarter of 2019 and 2020.

“Maraming ayaw nang mag-baboy, e,” said Alfred Ng, vice chairman of the National Federation of Hog Farmers (NFHF). Around three-quarters of the country’s hog population is from small, backyard farmers, while the rest belongs to commercial farms.

In an attempt to combat the virus, the DA began culling hogs within a one-kilometer radius from an infected pig. This radius was later reduced to 500 meters. Backyard farmers would then receive a P5,000 compensation for each pig killed, yet this price is too low considering the production cost of raising a pig. The NFHF estimated that raising a piglet could already cost a farmer up to P3,500.

Commercial hog raisers may also avail loans from LandBank that could cover up to 80 percent of their swine production or feed milling operation projects. This scheme, dubbed the SWINE program, however, leaves out backyard farmers. The loan imposes a three percent annual interest and requires collateral such as parcels of land.

With an indemnity payment too low and a loan program inaccessible to small farmers, some hog farmers have resorted to discreetly selling pigs, though they are within an ASF infection area, Ng observed. This practice, then, raises an issue of food safety, which could be resolved if the government would be more generous with their indemnity for hogs culled.

“Kung medyo mataas yung ibibigay mong ayuda o compensation, o sige, willing ako kahit na kaunting lugi o walang lugi, i-surrender ko yung baboy sa’yo (gobyerno). Babayaran mo naman ako, e,” Ng added.

On April 6, the DA already increased the indemnity to P10,000. This, however, came in the form of insurance from the Philippine Crop Insurance Corporation that requires prior registration in both national and barangay-based rosters. The insurance policy also requires farmers to comply with minimum biosecurity standards of the Philippine College of Swine Practitioners.

Some farmers, however, remain hesitant as some have experienced delays in claiming their insurance, Ng said, adding that the paperwork they had to comply with just to apply in the first place is already voluminous. “Andaming papeles na hinihingi. Kaya, natatakot ang mga tao na, at the end, malulugi rin ako, wala akong makukuha diyan.”

Long-run Prospects

In IBON’s proposal, P220 billion is allotted for agricultural support—the second-largest in their proposal, second only to the cash subsidies for low-income families. The SHIELD Bill earmarked a similar amount. Direct cash aid to farmers is essential now, yet investing in agricultural infrastructure, particularly in biosecurity is also important in the long run.

Under Bayanihan 2, only P24 billion was allocated for agricultural support—less than half of the P66 billion request President Rodrigo Duterte told Congress during his 2020 State of the Nation Address.

For crop farmers, a big stimulus would mean investing in free and better irrigation access, Africa noted. For livestock, improving the country’s biosecurity checks at our customs border would most definitely prevent yet more animal diseases from coming into the country.

The ASF, for instance, is not endemic in the Philippines—it came from outside the country. According to the DA’s disease surveillance, contaminated food products might have brought the virus into our country. This could have been prevented if the country had had strict biosecurity protocols in place at ports of entry.

It was only last July 2020 that the government announced that it would construct the country’s first-ever border inspection facility for imported goods. Currently, the National Meat Inspection Service only checks and tests imported meats after they have arrived at their respective importers’ warehouses.

“Investing in agricultural infrastructure is, of course, essential for improving farm productivity and raising rural incomes over the long-term,” said Africa. “Outbreaks such as ASF will only be prevented or controlled if the government has the necessary corresponding biosecurity infrastructure. Budget cuts prevent this.”

This program is included in the SHIELD Bill. The measure paves the way for the industrialization of the agricultural sector as it plans to inject billions—from redistributing land to farmers to production and post-harvest support. The bill, however, has yet to pass the house.

Policy Reversal

The story of the country’s poultry farmers tells a different kind of economic stimulus they need. Though they have not been hit by a kind of zoonotic disease like ASF, their sector has been severely impacted by the country’s incessant importation amid the pandemic.

“Sila (hog industry) ay biktima na ng kapabayaan ng gobyerno saka sakit. Kami ay biktima ng policy nitong import liberalization ng gobyerno,” said Bong Inciong, president of the United Broiler Retailers Association (UBRA).

Since the pandemic began, their situation has worsened as production costs have skyrocketed while farmgate prices have plummeted (see sidebar 5) due to imported chicken meat penetrating the country’s markets. This, Inciong noted, has forced many chicken farmers to scale down or close their farms altogether.

“Lagi na lang ‘tong nangyayari, taas baba, collapse and rise. Minsan, maganda, minsan pangit. Kung titingnan mo yung long-term trend sa agriculture, paatras,” he said.

For hog farmers, their demands go beyond the direct cash injection into their industry. For the country’s local poultry industry to recover, the government must sever international obligations that allow other countries to easily flood local markets with cheaper, imported chicken meat. He cited, for instance, the country’s commitment to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Under the trade treaties to which the country is party, a part of a product’s total import, called the minimum access volume (MAV), will enjoy lower tariffs. For chicken meat, the first 24.5 million kilograms, while for pork products, it is the first 56 million kilograms. Poultry and pork products under the MAV enjoy 10 percent less tariff than that of their out-of-quota counterpart.

As an alternative, Inciong said the government should consider removing the MAV to reduce imported meats. After all, chicken and pork importation exceeded the MAV about 17 and five times, respectively. But, just last month, President Rodrigo Duterte increased the MAV allocation for pork by 350,000 metric tons, further making the country an attractive destination for imported meats.

While, in theory, he said, liberalization of trade could spur competition, this did not happen since domestic mechanisms were not in place to help local industries. Unlike other WTO nations, the government did not invest in modernizing the country’s agriculture, Inciong said. The economic crisis brought by COVID-19, then, only exacerbated their preexisting situation.

“Yung mga problema namin sa presyo, are mere symptoms,” Inciong said. “Ang root [cause] of the problem ay yang government policy na wala kang support, you are being forced to compete with products from countries which heavily subsidize their agricultural systems.”

An Omnibus Stimulus

According to IBON, the demands of various sectors could account for up to P1.5 trillion fiscal expansionary response. This plan would not only provide financial assistance to sectors, but would also invest in them.

This is the most ambitious and by far the largest stimulus package proposal in the Southeast Asia region. This plan, if heeded, is a direct opposite of the government’s economic recovery plan of doling out large corporate tax cuts, supply-side fiscal policy, and shortchanged fiscal stimulus (see sidebar 6). This is in contrast to the government’s previous large spending packages which have been funded through borrowing and savings.

For these groups, a meaningful stimulus package would not only resolve the immediate COVID-19 crisis but would also help build a more resilient economy, taking into account the longstanding ills sectors have been suffering.

“Big borrowing is fine if this is for the large COVID response and stimulus package that we so badly need, but not if it is just funding an unchanged ill-conceived infrastructure obsession, or going merely to repay past debts, or going to militarist purposes,” Africa said, emphasizing that it would be perfectly fine to borrow if the lowest-income families would benefit.

After all, key economic sectors would not survive if consumers were too empty-handed to spend. “Ang problema ngayon ay bumaba yung demand at saka wala na talagang pambili ang mga tao,” Inciong quipped.

“A genuine COVID-19 recovery plan has to be anchored on substantial ayuda to the poorest Filipino families. It is a meaningful stimulus to the economy because the increased consumption spending means that even small enterprises now have a reason to stay in or even expand their businesses,” said Africa. “Big ayuda is a key element for stimulating aggregate demand.” ●

Infographics by Kimberly Axalan.