Ah, the joys of being an applied science major—observing how chemical reactions are carried out, confirming that 45 degrees is, indeed, the optimal angle to reach the farthest distance of a projectile, seeing how red blood cells expand or shrink depending on their environment.

Whatever theories students learn in lecture classes, experiments would provide a more in-depth and observable explanation for. But, a little over a year ago, COVID-19 took the world by storm and the doors of laboratories have since closed for aspiring scientists.

With the surge of COVID-19 cases and the lack of a concrete plan from the government, the reopening of schools seems like a distant dream.

Now, students bear the burden of understanding their lessons even without enough supervision from professors minus the avenue to test theories as in lab classes, leaving applied science majors worried and insecure about being a competent scientist for the people.

On Weak Foundations

Christian Ende, a first-year BS Chemistry student from UP Diliman, recalls the thrill and anxiety he felt when the UPCAT results were released last year. With the outbreak of COVID-19, the results kept on getting postponed. After the tireless wait, he finally got a hold of his results—he got into his dream campus.

For Ende, to study in the country’s national university with a center of excellence in chemistry has always been the way to go. Since junior high school (JHS), he has always enjoyed chemistry, despite its difficulty. However, with the shift to online classes, his excitement to study the course has declined due to the absence of hands-on lab experiments.

Coming from a public high school in Mindanao, Ende was not able to explore the lab side of science. “I only had three semesters na mayroong lab noong high school. I spent my JHS years po kasi in a barangay national high school and kulang talaga sa laboratory equipment,” he said.

In senior high school, choosing to be part of the STEM track moved Ende’s path a bit closer to his dream of becoming a scientist. “Sa senior high school lang po ako naka-try humawak at gumamit ng microscope, nakasuot ng laboratory gown and naka try mag-experiment,” he shared.

In a research by Arlyne Marasigan and Joanna de Borja published in the International Journal of Research and Publications in 2020, they found out that the Philippines gives little focus to science laboratories in public schools. This can be seen in the inadequacy of labs to cater to the student population, limited equipment, and lack of trained teachers in lab safety guidelines.

While SHS was an upgrade from Ende’s JHS experience, it still was not enough. A total of 36 students had to cram into a small lab where they would share the equipment. In their biology lab, six students had to take turns using one microscope.

“Nababahala po talaga ako. Baka kasi gagraduate akong di marunong mag-titrate kasi never ko pa pong nasubukan,” Ende said, worried about how his poor foundation in chemistry lab and the pandemic may have affected his future in the field. Titration is one of the common lab methods of chemical analysis that requires immense precision to do—a skill that chemistry majors must have. “Sa course pong ito, hindi lang sapat na alam ko laboratory skills, I have to master it,” he continued.

Currently, Ende is taking two lab classes, General Chemistry II and Fundamentals of Biology I. In his first semester, he also took General Chemistry I. Before the pandemic, general chemistry lab classes in the Institute of Chemistry (IC) were done in pairs. At the start of the semester, students are assigned lockers in the labs where they could find materials to use for experiments such as test tubes, beakers, and flasks. Meanwhile, in the biology laboratories, experiments were done in groups of five where each group was given three to four microscopes.

With the online setup, instructors would just send pre-recorded videos of the experiments to students and the corresponding raw data results for analysis. This robs students of the lab skills and practices that are essential foundations for their higher chemistry courses.

In fact, moving exams were a staple of the IC’s general chemistry classes. Instructors would man different stations and observe how well a student performs tasks like pipetting and titration. During classes, lab safety rules are always strictly observed—wearing lab gowns and goggles inside the lab, using fume hoods to handle toxic substances, disposing of wastes properly, among others.

“May mga cool experiments na po kami last sem na I think would be best enjoyed kapag [face to face] kagaya na lang nung unknown analysis. Instead po kasi na makita mismo yung observations, we were given a table na lang po and andun nakasulat yung observations for the ion tests and confirmatory tests,” he lamented.

Although worried, Ende’s dream to proceed to medicine after his chemistry degree has not faltered. “The pandemic even reinforced my reason para maging doktor kasi pinakita ng pandemic ang kakulangan ng doktor sa ating bansa,” he said.

On Thesis Dilemmas

Science has always been the passion of Edward Jairus Doce, a third-year BS Chemistry student in UP Diliman. Even as a kid, his idea of free time was reading science books. They painted him a picture of what he wanted to be in the future: performing experiments in a lab, test tube in hand, chemicals of different colors lining the countertop.

For a while, Doce had that. Having spent his first three and a half semesters inside the walls of the IC, he was able to complete three out of the seven lab classes in their curriculum under a face-to-face setup.

However, despite having almost reached the end of his undergraduate journey, like Ende, Doce is worried about not having fully mastered the lab skills he needs as a chemist.

"Alam mo yung natatakot ako na baka mamaya pagbalik ko nang lab, di ko na alam yung gagawin ko, ang dami ko nang nagagawang mistakes,” he said, sharing that this was his biggest concern, especially since it has been a year since he was in the lab.

He was almost midway through his analytical and organic chemistry lab class or Chem 101.2 when the pandemic hit. With everything forced to transition online, students were not able to get to the analytical part of the course, which Doce had actually looked forward to.

“Kasi yung analytical part, yung lab na iyon, yun yung lab na dapat magha-handle na kami ng sobrang daming instruments. So maghahandle na kami ng NMR, ng gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, mga atomic spectroscopy, yung mga ganon, basta ang dami naming instruments na maihahandle nun,” he explained.

Currently, Doce is taking the course Laboratory Techniques in Biochemistry, where, unlike in general chemistry labs where videos of the experiment were provided, experiments were not conducted at all. Instead, the processes were just explained to them and they were given different lab scenarios that they may encounter in the future and taught how to calibrate the procedures in those cases.

Being unable to explore the different experiments firsthand has made it difficult for applied science students to get a grasp of what they want to focus on for research. In the BS Chemistry curriculum of UP Diliman, third-year students are highly encouraged to have a topic for their thesis already.

Although he still does not have a topic for thesis, Doce already has a vague idea of what he wants to pursue under the advisory of Prof. Cynthia Grace Gregorio. In Gregorio’s lab, they try to find geographical indicators of local alcoholic beverages in the country. Originally, they had planned to go to the Cordilleras to get samples of Tapuy, an alcoholic beverage originating from Banaue and the Mountain Province. However, because of the pandemic, Doce has no idea how to go about his thesis now.

In an assembly with the students and faculty of the IC on February 2, students were told that they had the option to do a dry lab, which focuses on the theoretical side of chemistry, or a wet lab, which performs actual experiments and testing. If they choose to do a wet lab thesis, the research assistants would be the ones performing the experiments. The results will just be sent to them afterwards.

"I have half a mind na mag-residency, mag-LOA [leave of absence] next sem para lang by the time na bumalik na ako, at least may lab na. Magagawa ko na ang thesis ko with lab talaga, wet lab," Doce shared.

He is not alone in wanting to take a break. Students all over social media have expressed the need for an academic break or ease because of the overwhelming effects of the pandemic. In the online petition by the Rise for Education - UP Diliman last year, 6,666 individuals called to end the semester and demand a mass promotion. This year, with Metro Manila in an enhanced community quarantine once again, students are again clamoring for the suspension of classes and academic deadlines.

Like Ende, despite the disheartening setup amid the pandemic, Doce is set on finishing his chemistry degree and proceeding to medicine. If he decides to push through with filing for LOA, Doce plans to use that time to prepare for the National Medical Admissions Test, which he has to take in his fourth year.

On What Comes Next

“Chemistry is a professional course and chemists have to be certified before they can perform analysis and issue results on laboratory services. The online setup essentially peels off several layers of training they would normally get from hands-on courses,” Dr. Herald Lim, the director of the IC, said.

Indeed, the closing of schools has put a heavy toll on students. The online setup has passed to them the burden of gaining the needed skill set to qualify for a place in the post-graduate jungle of overworked and underpaid laborers.

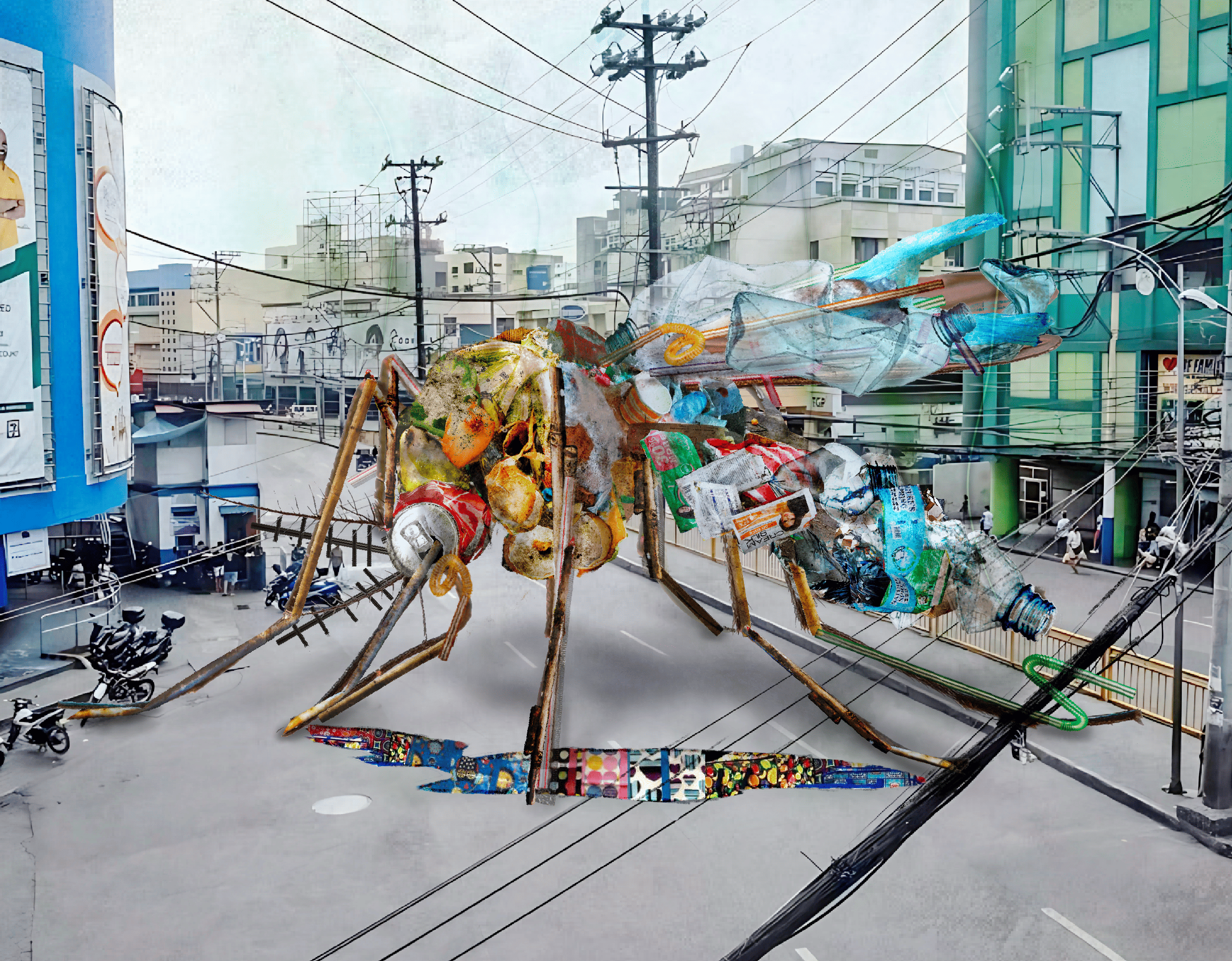

However, the reopening of schools comes at a cost that the Philippines is far from ready to pay for. The World Health Organization's recommendations for reopening schools include mass testing and contact tracing, which billions of loans and a year after, the government has still yet to deliver.

If anything, the pandemic situation in the country has only gotten worse. In fact, due to the surge in COVID-19 cases, the UP Philippine General Hospital, the pilot institution to conduct face-to-face classes in the country, had to transition back to the online setup.

Considering the many repercussions of going back to campus, the IC has not applied for limited face-to-face classes yet. “The health of the students is our top priority. All other considerations simply follow from how well we can preserve that even if relaxation on restrictions can be afforded,” Lim said. Instead, the institute is looking into how to go about the face-to-face system if and when it resumes—safety protocols and rational timings for bridging lab courses such that minimum skill levels are met without delaying graduation.

Frustrated and desperate, both Ende and Doce echo what millions of Filipinos have been tirelessly calling for since day one of the pandemic: Provide a concrete plan for mass testing, secure enough vaccine deals for the country, and listen to science and research. “Hindi po biro ang pandemyang ito, maraming buhay at kinabukasan ang naaapektuhan dahil dito,” Ende said. ●