Upon the historic arrest of former President Rodrigo Duterte at The Hague as he stands trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) over charges of crimes against humanity, the long struggle for justice for victims of the bloody drug war seemed to have finally gained greater ground. Yet the promising implications of the detention started to be increasingly undermined by the Duterte camp’s move to mount a coordinated campaign meant to discredit victims of the previous administration’s carnage.

There seems to have been a greater resurgence of a common picture prevalent during Duterte’s reign: narratives of victims were demeaned, the dead were painted as violent thugs who deserved their fate, and the “adik” boogeyman was deployed to dehumanize those targeted by extrajudicial killings. Others go as far as sending death threats to victims’ families who choose to speak out until now.

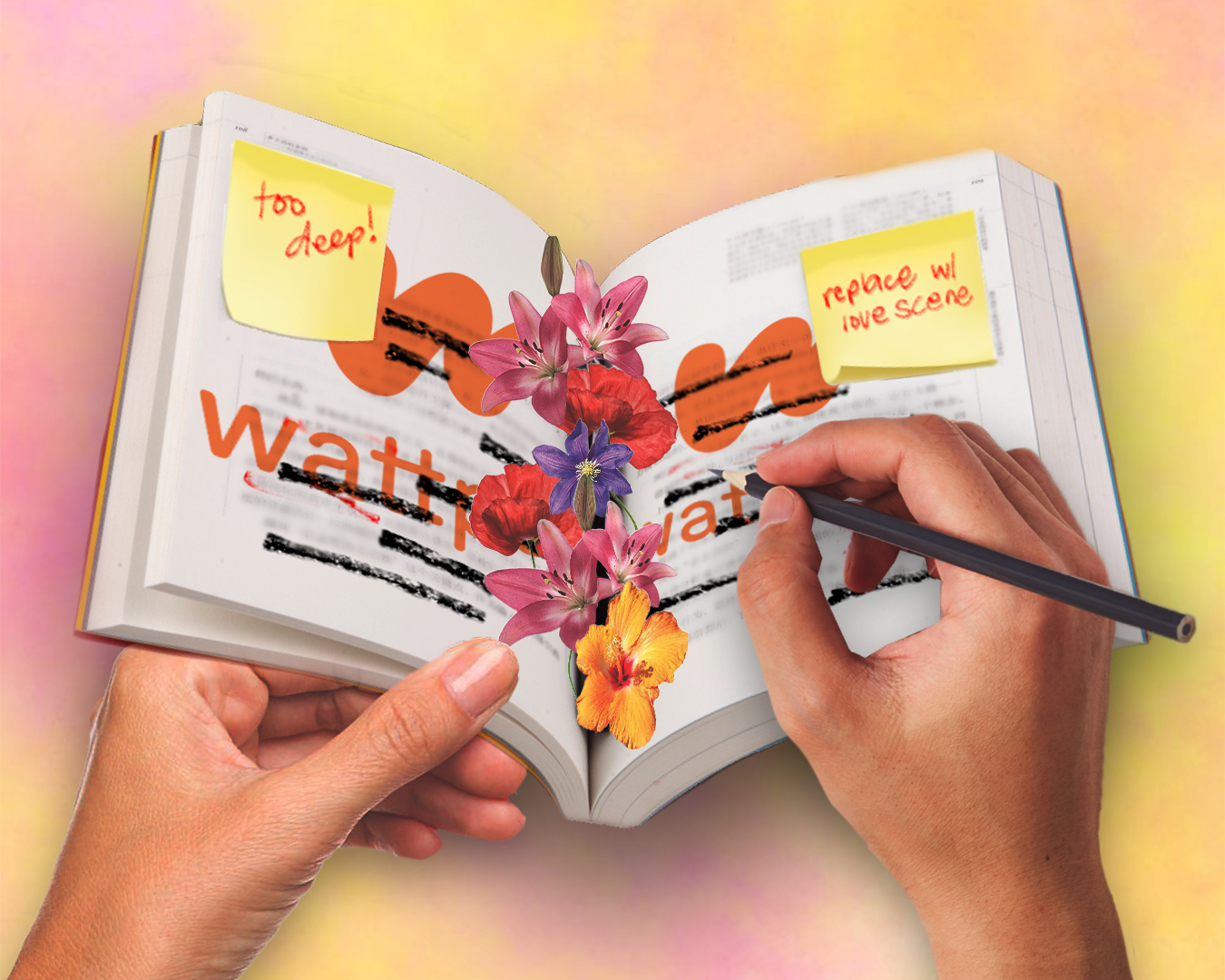

Yet amid the noise that muddles the truth, a new wave of works exemplifying narrative journalism and testimonial literature came into the light through Patricia Evangelista’s “Some People Need Killing” in 2023 and Kenneth Guda’s “Peryodismo sa Bingit” in 2016 and “Presinto Uno” in 2024. These books serve as potent weapons that subvert epistemic injustice, centering the voices and resistance of those who have long been dehumanized and marginalized in the dominant discourse.

Through Testimonies

As trolls peddle the denialism of the atrocities during Duterte’s regime, pro-Duterte vloggers and content creators fuel the fire of disinformation and vilification of victims. Using the same mechanisms as the previous presidents, these people tap into citizens’ latent anxieties, inflate them, and direct them toward slain innocents.

In doing so, extrajudicial killing victims are portrayed as subhuman addicts whose deaths are “necessary” for the common good. Or, as what Evangelista’s book title states, those depicted as the people who need killing. This is how bloodbath is legitimized, normalized, and reproduced.

With such a message, not only are Duterte’s actions excused, but the pain and trauma of the victims’ families are also compounded. They are disbelieved, tagged as a hoax, and seen as bearers of fake news.

Survivors are, thus, subjected to what Miranda Fricker conceptualized as testimonial injustice. This occurs when a group of people is deliberately and discredited unfairly due to prejudice about their identity or social position. In the Philippine context during the drug war, the arduous process of exacting accountability typifies epistemic injustice from the dominant discourse up to trial courts.

The rise of testimonial literature thus serves as a beacon of hope that may rectify the perennial disregard that survivors have long been subjected to.

Evangelista’s work counters testimonial injustice, as it centers the narratives of victims who were often dismissed during Duterte’s regime. Through meticulous interviews and engagements with relatives of drug war victims, the book unveils the faces often obscured by mere statistics: the orphaned children who were shot down in front of their parents, weeping mothers clutching photographs of sons and students marked as “addicts,” and those executed without trial, among others.

While Evangelista was able to capture readers through the emotional weight of people and their stories, Guda’s works do the same and more: he also underscores the active participation of the oppressed in contesting their conditions. He profiles the lived experiences of victims, activists, and ordinary citizens who share a collective plight and political struggle. These include victims of Oplan Tokhang and abusive officers in a prison in Tondo, striking workers, and Lumad evacuees displaced by rural militarization.

These works, thus, exemplify not merely a type of literature, but are wielded as critical tools of resistance against an information landscape that buries the voices of the slaughtered.

Restoring the Right to Speak

Although testimonial literature is not new, it is taking on a broader and relevant role in the Philippine context at a time when disinformation and memory distortions are surging.

This type of literature finds its roots in Latin America, in the wake of militarization and dictatorship from the late 1970s until the early 20th century. Testimonial literature became widely known as a political and literary invention that challenged dominant narratives, according to Georg Gugelberger and Michael Kearney in Latin American Perspectives. Such works became a platform for the marginalized who are reclaiming their voices.

Memories of the silenced are thus centered, recognizing the suffering and trauma inflicted against certain groups of people. Literary witness, seen this way, should “belong to the complicated terrain of truth telling, justice, injury, and resistant agency,” wrote gender studies scholar Leigh Gilmore in a journal published by Modern Language Association.

With Evangelista’s particular focus on the truth and injuries of the victims and Guda’s emphasis on justice and resistant agency, such works are able to empower and go against the tide of prevailing epistemic injustice.

These pursuits, however, do not stop at the epistemological level. These are seen as first steps in concretely challenging prevailing social injustices.

Pages that Protest

Both Evangelista and Guda, embedded in communities, do not stop at the level of transmitting their stories. Evangelista’s book, for one, also opened avenues for mediums of mobilization and gatherings. Last year, for example, volunteers RESpond and Break the Silence Against the Killings organized victims’ families at a church in Payatas to retell their stories and continue the fight.

A group of volunteers gathered around to listen through stories of victims (Patricia Evangelista’s Instagram Post)

Guda’s emphasis on the resistance of communities also shows how their valiant reclaiming of their narratives emboldens them to persist in the struggle. Such a thrust becomes more important now that survivors and activists are increasingly pushing back as Duterte’s reckoning at the ICC already commences.

In this way, testimonial literature transforms and becomes part of a larger battleground for truth and justice.

And so, as the struggle for accountability for the thousands of victims killed under Duterte’s reign continues, their stories will also live on. Through these narratives, we are reminded of the exigency of remembering, resisting, and reclaiming the voices of the ones who have long been silenced and discredited. ●

First published in the May 27, 2025, print edition of the Collegian.