Despite farmers’ repeated calls to junk the Rice Tariffication Law (RTL), now over a year since its enactment, many senators, including one of the RTL’s main proponents, Senator Cynthia Villar, all of a sudden shifted gears and asked Agriculture Secretary William Dar to stop the Bureau of Plant Industry (BPI) from issuing any more rice import permits, especially at the same time as local farmers’ harvest season.

This backpedaling comes several months too late, as the unforgiving effects of the RTL, combined with the pandemic, have left local farmers practically penniless.

However, the Department of Agriculture (DA) estimates that the total rice imports will reach 2.6 million metric tons by December 2020, even greater than last year’s 2.3 million metric tons of rice imports and comprising over 20 percent of the country’s annual rice consumption.

Increasingly large volumes of rice importation have direct, long-lasting consequences as it slowly kills the palay industry, said Ariel Casilao, vice chairperson of pro-peasant party-list Anakpawis, in a video interview with Kodao Productions, October 19.

Farmers are forced to sell below the current cost of production of at least P15 per kilo, factoring in inflationary costs from the 2018 TRAIN Law and all other conditions, according to the computation by Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP). The peasant group said that the current average price range of palay is P12 to P14 per kilo in most provinces, a far cry from what the government claims to be its farmgate price of P19 per kilo, on average (see infographic), and not nearly enough for farmers to earn a decent income.

The Weekly Cereals and Fertilizers Price Monitoring, a survey conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority, purposively collects, among other price types, farmgate prices based on a sample of at most five respondents from each province. Though, even before the implementation of the RTL in February 2019, the farmgate prices of local rice had been in decline, such downswing accelerated ever since, most steeply so in mid-August 2019 amid reports of farmers in Nueva Ecija selling their harvest at as low as P7 to P8 per kilo.

The farmgate price surged momentarily in the first months of the pandemic, amid panic buying, local governments’ relief efforts, and stockpiling regionally. April 2020, in particular, coincided with severe lockdowns and coronavirus restrictions. Yet, since then, the palay prices normalized to pre-pandemic levels in consecutive weeks, following the same downturn, as consumers’ demand diminished and imports edge out local produce in the market. With the peak harvest season in October, millers who fear losing any more revenue are even more discouraged from buying from local farmers.

“Malakas ang panawagan natin na ibasura [ang RTL] dahil tinamaan ng magsasaka ng bigas, pero hanggang ngayon ayaw pa nilang i-repeal. Hihintayin pa nila ang limang taon, kaya sinabi natin, aanihin pa ang damo, kung patay na ang kabayo?” said KMP chairperson Danilo Ramos in an online interview with the Collegian.

In response to the continued drop in palay prices in the middle of the COVID pandemic, farmers groups called for an urgent and efficient release of food and cash relief. But months into the pandemic, distribution of aid remains slow and many farmers have yet to receive any aid.

“Lahat ng ito ay umabot sa puntong dumulo roon sa talagang tinamaan sila nang husto. Nawalan at hindi nakaabot yung ayuda, wala ngang subsidyo roon sa pagtatanim mo ng palay,” Casilao said. “Tuloy-tuloy ang atake sa mga komunidad ng mga magsasaka at mga organisasyon nito para tayo patahimikin at pahintuin sa isinusulong nating mga konkretong solusyon tulad ng economic stimulus package.”

Inefficient aid distribution

In anticipation of even harder times, farmers already began petitioning the government, as early as March, to provide both cash assistance and production subsidies to lockdown-stricken farmers.

On top of the demand for a P10,000 emergency cash assistance to 9.7 million farmers and fisherfolk, KMP has also called for a production subsidy worth at least P15,000 for over two million rice farmers to boost local rice production. The latter has not materialized, but cash transfers did, though ploddingly.

Though programs for cash assistance and several others have been approved, they have so far failed to disburse cash aid to farmers quick enough to be of immediate help.

As early as April, farmers’ group Bayanihan Para sa Agrikultura Laban sa COVID-19 asked the DA to expedite the release of the 2019 and 2020 appropriations for the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF), a program under the RTL for the provision of production subsidies, farm machinery and equipment, and seed development, among others. But, as of October, only 32 percent of the P10 billion fund has been committed to specific agencies and projects, according to Dar.

Back in July, the DA merely cited bureaucratic issues to justify the months-long delay in the release of the funds. Dar even admitted in a statement last August that farmers were expected to benefit from the program early next year at the earliest, by which time, however, farmers would have already spent most of this year struggling to survive with little to no income.

Another program is the Financial Subsidy to Rice Farmers, under the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, which included P5,000 cash assistance each to only 591,246 of the 2.7 million rice farmers in the country, which Ramos described as being like a drop of rain in an entire forest.

The DA’s nationwide self-sufficiency program, Ahon Lahat, Pagkaing Sapat (ALPAS) Laban sa COVID-19, otherwise known as “Plant, Plant, Plant” program, received a mere P11.39 billion out of the total P389-billion fund released by the government as of September, or 2.9 percent of the total, meaning that aid has yet to reach even one percent of the total 9.7 million rural people.

This is not the only instance of the DA’s general lack of transparency, with the recent exposure of a possible repeat of the Fertilizer Fund Scam earlier this year. The DA was accused of buying overpriced fertilizer for P995 per 50-kilo bag in compromised bidding, much higher than the current market price of P800 to P830 per bag.

“Ang masakit pa, doon sa kaunting tulong para sa magsasaka, [kinupit] pa ng opisyal ng pamahalaan, particularly ng DA. Sa tingin natin, hindi bababa sa P271 milyon yung [kinupit] nila. Nagpapakita ito kung gaano sila ka-walang malasakit,” Ramos said.

Crisis after crisis

Ever since the RTL was signed into law, farmers, farm workers, and leaders of farmers groups like Renato Gameng, one of the founders of the San Francisco Farmers’ Association in Isabela, have campaigned for higher wages and farmgate prices of rice to forfend their bankruptcy.

Gameng was among those who signed a petition to junk the RTL in solidarity with his fellow farmers who had been affected by the law. This must have likely led to his being red-tagged and suspicions that he is being followed and surveilled, he said in a media forum organized by the local chapter of Karapatan, a human rights watchdog, October 7. He insisted, however, that the issue should be about the policy’s impacts on the ground, not about their political affiliations.

While the government would justify the RTL with claims that it would help Filipino farmers become more competitive amid liberalization, local farmers, without sufficient production support, stand little to no chance of competing with cheaper imported rice from countries like Vietnam or Thailand whose production costs are as low as P5 to P6, according to KMP. Vietnam has been able to reduce input costs and boost rice production by pouring money into farm infrastructure, irrigation projects, and rice research and development, which the Philippine government has yet to have much success in.

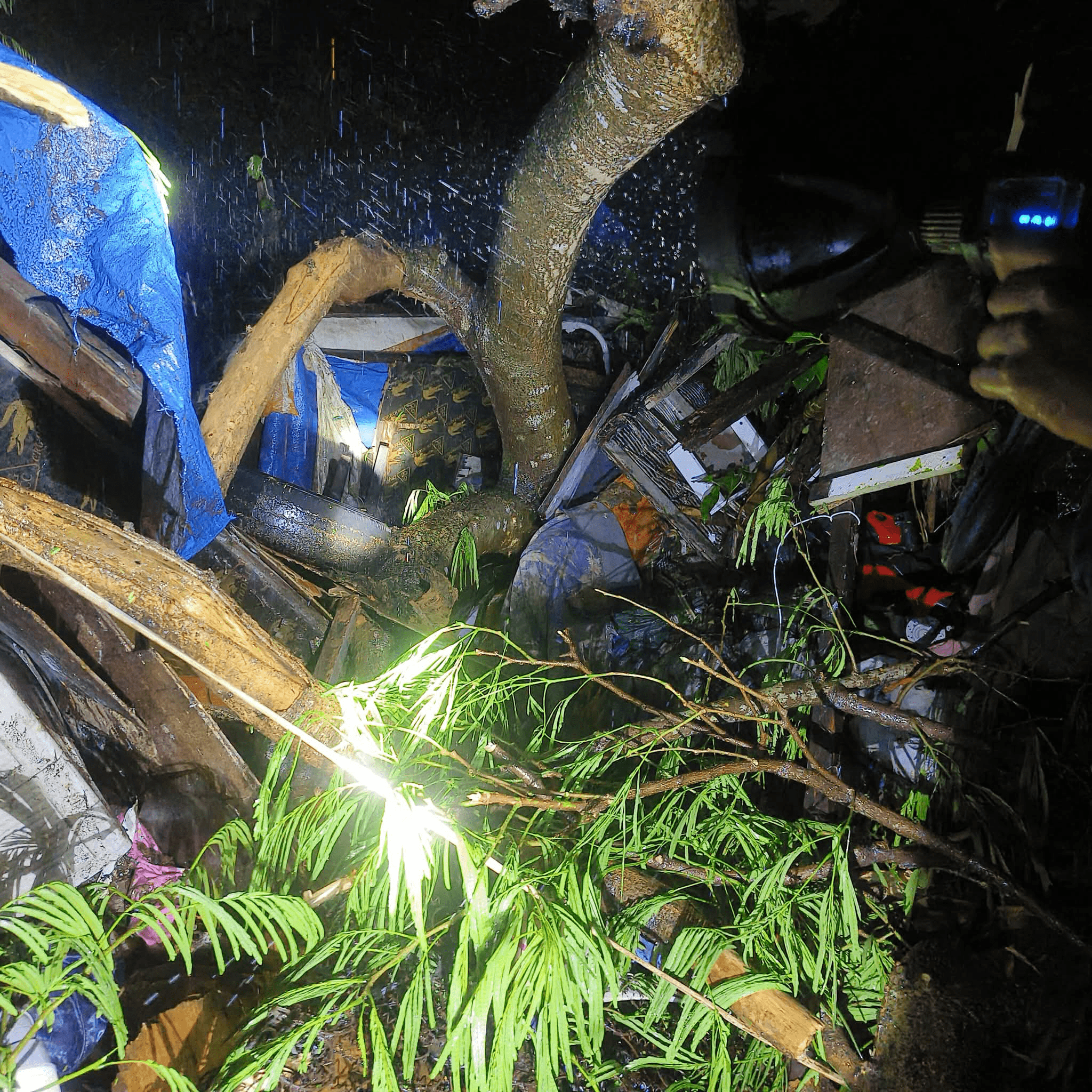

This had proven most problematic when the pandemic struck. The law, around this time, had induced a sharper plunge in palay prices. In fact, the current price of P12 per kilo of palay is just the equivalent of an empty sack or a kilo of hog feed and makes the commodity even cheaper than a COVID mask.

Early into the pandemic, farmer groups and advocates already called on the DA to increase government procurement of palay from local farmers. International organizations such as the World Bank and the World Economic Forum had warned of possible disruptions to the global food supply due to the pandemic, from increased costs of farming to export bans in major food-producing countries.

In fact, Vietnam, the country’s biggest source of rice imports, was one such exporter that announced last March it was going to drastically cut exports to save food supply for its own people, sending DA officials scrambling to ensure the Philippines had enough rice inventory to last through the crisis. The DA initially proposed to import 300,000 metric tons of rice, which even the Philippine International Trading Corporation challenged until eventually, when Vietnam lifted its import ban, the plan was abandoned.

To fend off a food crisis, governments needed to find ways to boost their local production capacity for essential food and agricultural products. Hence, the need to focus on increasing government procurement of palay, which would directly address the decline in prices, advocacy group Action for Economic Reform (AER) wrote in a statement earlier this month.

The National Food Authority (NFA), whose sole mandate is to ensure buffer stocking for calamities and emergencies, has the means and duty to buy palay at the standard P19 per kilo so that farmers are no longer forced to sell at the current farmgate price of P12.

Even though P7 billion from ALPAS COVID is set to be used to increase the funds of the NFA, palay procurement continues to be slow. In August, NFA Administrator Judy Carol Dansal explained this away by pointing to the lack of rice milling facilities and the government’s low buying price.

Meanwhile, the DA continues to allow the BPI to give out rice import permits even during harvest season, and yet ironically still has trouble in efficiently rolling out much needed aid and subsidies to farmers.

Owing to the government’s relative lack of priority given to the country’s agrarian sector, food security has now been compromised and millions of Filipinos are going hungry. In July, a report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization listed the Philippines as having the highest count of food-insecure citizens, with 59 million Filipinos going hungry from 2017 to 2019.

A change in policy is long overdue, especially during a pandemic, to break with the government’s decades-long insistence on opening the economy up to imports, despite local abundance in rice, poultry, livestock, fish, and more.

“Dapat ipatupad ang tunay na repormang agraryo at pambansang industriyalisasyon, at palitan ito ng bagong programang maglilingkod sa sambayanan,” said Ramos. “Hanggang hindi nagbabago, malamang ang dalawang taon ay paghihirap pa kay Pangulong Duterte.” ●

Published in the Collegian’s October 2020 digital issue.