One morning in 1978, Tony Oposa and a friend set out to hike Mt. Manunggal, the highest mountain on the narrow island of Cebu. They thought of trekking through a real, old-growth forest—one whose ecosystem had not been disturbed by human activities, such as commercial logging—but they were surprised that they could not find any. Instead, what they saw was bare and barren land.

Ten years later, Oposa learned that only about 800,000 hectares remained out of 16 million hectares of old-growth forests that once covered more than half of the archipelago’s land area in the 1950s. The Marcos administration had given permits to hundreds of logging companies—most of which were controlled by Marcos loyalists—to cut down 3.9 million hectares of old-growth forests, about five times what actually existed at the time. At the rate deforestation was going, the remaining old-growth forests in the country would be wiped out before the turn of the century.

Oposa’s upbringing had instilled in him a deep love of nature. He was raised in Cebu by his grandparents, who took care of him after his parents moved to the United States for his mother’s cancer treatment. His grandfather, whom he called Papa Oto, was a harbor pilot at a major seaport on the island. As a child, he would tag along as Papa Oto rode tugboats that maneuvered big ships into and out of the harbor, and he soon developed a love for the sea.

Later on, Oposa inherited from his grandfather a small coconut farm on the remote island of Bantayan, just off the northern tip of Cebu, in the Visayan sea. The farm was surrounded by palm trees, white sand, and turquoise waters. Oposa has not sold it despite lucrative offers amid a real estate boom.

The Children’s Case

Oposa knew that something had to be done about the unrestrained deforestation happening across the country. If things went on as they were, his children and his children’s children would be left with a wasteland.

Tired of government inaction and fed up with futile debates in Congress and the media, he decided to take matters into his own hands. One day, in 1990, he filed a case before the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Makati seeking to compel the government to cancel all existing timber licenses held by logging companies and to cease from issuing new ones. All his lawyer friends thought he was insane.

He named as plaintiffs 43 minors, including his own children, representing their generation and generations yet unborn. This was a creative gamble; the courts’ rules of procedure dictate that only those of legal age could sue, and they had to be directly affected by an already existing controversy. It was unclear whether the unborn could bear any rights at all in the eyes of the law.

He did not name as defendants the logging companies, whose resources and clout would most likely lead to the defeat of the young, scrappy lawyer. He named, instead, Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources Fulgencio Factoran, a fellow environmental advocate who, on being apprised of the case, gave Tony a call and said to him: “OK yan, pare!” He was so surprised that he almost fell off his chair.

In filing the case, Oposa only wanted to articulate the problem in a formal setting, make all parties come to the table for a resolution, and draw attention to how logging companies were destroying our forests for profit. His goal was to tell a story in the way he knew how. Little did he know that Minors Oposa v. Factoran would revolutionize international environmental law and inspire dozens of environmental lawyers across the world to take on big corporations and file similar cases in their domestic courts.

The Rights of Posterity

Just four years before Oposa filed the case, members of the Constitutional Commission of 1986 had debated whether to include a specific provision about the environment in the constitution. Ed Garcia, a human rights activist and one of the framers, broached the inclusion of a provision that would mandate the State to recognize the right of nature “to follow its own rhythm and harmony.”

Other lawyers on the committee had objected; nature was not a person that could be given legal personality and granted a right. They had settled on a compromise, which ended up being Article II, Section 16 of the 1987 Constitution: “The State shall protect and advance the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.”

This was the constitutional provision on which Tony Oposa anchored his argument in Minors Oposa v. Factoran: By virtue of the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology, the courts had the duty to compel the government to cancel all timber license agreements and cease from issuing new ones. He knew this was a long shot; the provision had never been interpreted this way. But he wanted to tell a story and took his chances.

The RTC sided with the Solicitor-General and dismissed the petition, but Oposa, a tireless advocate intent on making a point, brought the case all the way up to the Supreme Court. To reinforce his argument, he used a concept that he came across in the work of another environmental lawyer, Edith Brown Weiss: intergenerational responsibility, which says that we who live today are mere stewards who have duties toward future generations.

This idea is so antithetical to our rabidly consumerist culture obsessed with short-term gains and concerned only with the present, so it was no surprise that Tony’s argument was considered radical.

Ripples and Waves

On July 30, 1993, the Supreme Court (SC) held that minor plaintiffs had standing to sue and could represent future generations based on the concept of intergenerational responsibility. “Every generation has a responsibility to the next to preserve [the] rhythm and harmony [of nature] for the full enjoyment of a balanced and healthful ecology,” the court said.

It also held that Article II, Section 16 of the 1987 Constitution was a self-executing provision, which meant that it did not need an implementing law passed by Congress to be operative. This was a novel interpretation, since it was commonly understood that the provisions of Article II—the Declaration of Principles and State Policies—were mere prods to Congress on what laws to enact and could not be invoked outright.

Environmental defenders across the world lauded the decision. It was cited in prestigious law journals. It inspired environmental lawyers across countries to invoke intergenerational responsibility to fight against environmental degradation. Tony Oposa instantly became a household name in international environmental law.

Despite the profound influence that the case has had in international environmental law, there are critics. Prof. Dante Gatmaytan, a constitutional law professor, argued in a journal article that the case offered “little outside of rhetoric,” and that the Supreme Court’s ruling on future generations’ right to sue was a mere aside—what in legalese is called obiter dictum, literally “by the way”—and had no effect on how the court would decide future cases.

He also said that the decision did not contribute toward stopping environmental degradation in the Philippines. The SC did not actually cancel the timber license agreements held by logging companies; it merely passed on the case to a lower court and asked Oposa to name as defendants the logging companies that held timber license agreements. But Oposa, then a young lawyer with a family to feed, thought it impractical to go against 92 logging companies in court and did not continue litigating the case.

Gatmaytan explained that, despite the court’s favorable ruling, it has since handed down many decisions inimical to the environment, which proves that Oposa was a mere aberration in the court’s general stance in favor of big corporations.

Although it may seem like the Oposa case did not lead to any concrete effects outright, it created immediate ripples of change in the Philippines and around the world. In 1991, while the case was pending in the trial court, Secretary Factoran used it as leverage and issued a department order banning logging in all old-growth forests in the Philippines.

Neil Popovic wrote in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review that the Supreme Court in Oposa “announced a powerful and influential exposition of intergenerational rights in the context of environmental protection.” Almost every article in international environmental law scholarship cites Minors Oposa v. Factoran. It is impossible to track and pin down the many ways in which the case helped stop environmental degradation around the world; what cannot be denied is that it changed how people understood their obligations toward nature and future generations.

Six years after the SC handed down its landmark ruling in Minors Oposa v. Factoran, Oposa waged another battle. Invoking the Environment Code and the same constitutional provision that he used in the Oposa case—the right to a balanced and healthful ecology—he filed a complaint to compel government agencies to clean up, rehabilitate, and protect Manila Bay, whose water quality had by then fallen way below the standards mandated by law. It went through the judicial mill for 10 years, and, in 2008, the Supreme Court released its decision in Metropolitan Manila Development Authority v. Concerned Residents of Manila Bay.

It ruled in favor of Tony and ordered 11 government agencies—including the MMDA, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Department of Health, and the Department of Public Works and Highways—to restore the water quality of Manila Bay to a level suitable for recreational activities, such as swimming and skin diving. The court required the agencies to submit quarterly reports to prove compliance with the ruling.

Peril and Promise

According to the international watchdog group Global Witness, 43 environmental defenders were killed in the Philippines in 2019, the highest in Asia and the second highest in the world. Datu Kaylo Bontolan, a Manobo leader, was killed in a military bombardment in northern Mindanao after he helped document the violence inflicted by logging and mining companies against the Manobo peoples. Last year, Bienvinido Veguilla, Jr., a DENR forest ranger, was hacked to death with a bolo by six suspected illegal loggers in a forest in Palawan.

Oposa himself is not unfamiliar with threats and intimidation. In 2003, with illegal dynamite fishing going rampant at Bantayan, he organized the Visayan Sea Squadron, a team of fishermen, lawyers, law students, and law enforcement agents that served outstanding warrants and conducted raids on manufacturers of explosives. A local daily reported that there was a million-dollar bounty on his head and that of Jojo de la Victoria, the leader of the squadron’s sea patrol, but they laughed it off. Two days later, de la Victoria was shot dead as he got out of his car and entered his home.

Oposa was devastated. At the funeral mass for de la Victoria, he remembers walking up to the church pulpit and, in a fit of rage and frustration, announcing to everyone present that he would avenge de la Victoria’s death by continuing the work of the Visayan Sea Squadron. Mere hours after the burial, they met up and identified their next target for a raid, an explosives manufacturer on an island that was a hotbed of dynamite fishing. “We turned our despair into a deliberate effort to continue our fight against dynamite fishing in the Visayan sea,” he said.

Oposa said that the killings will only stop if people in power—mayors, congressmen, senators, the president—decide to proactively support environmental defenders.

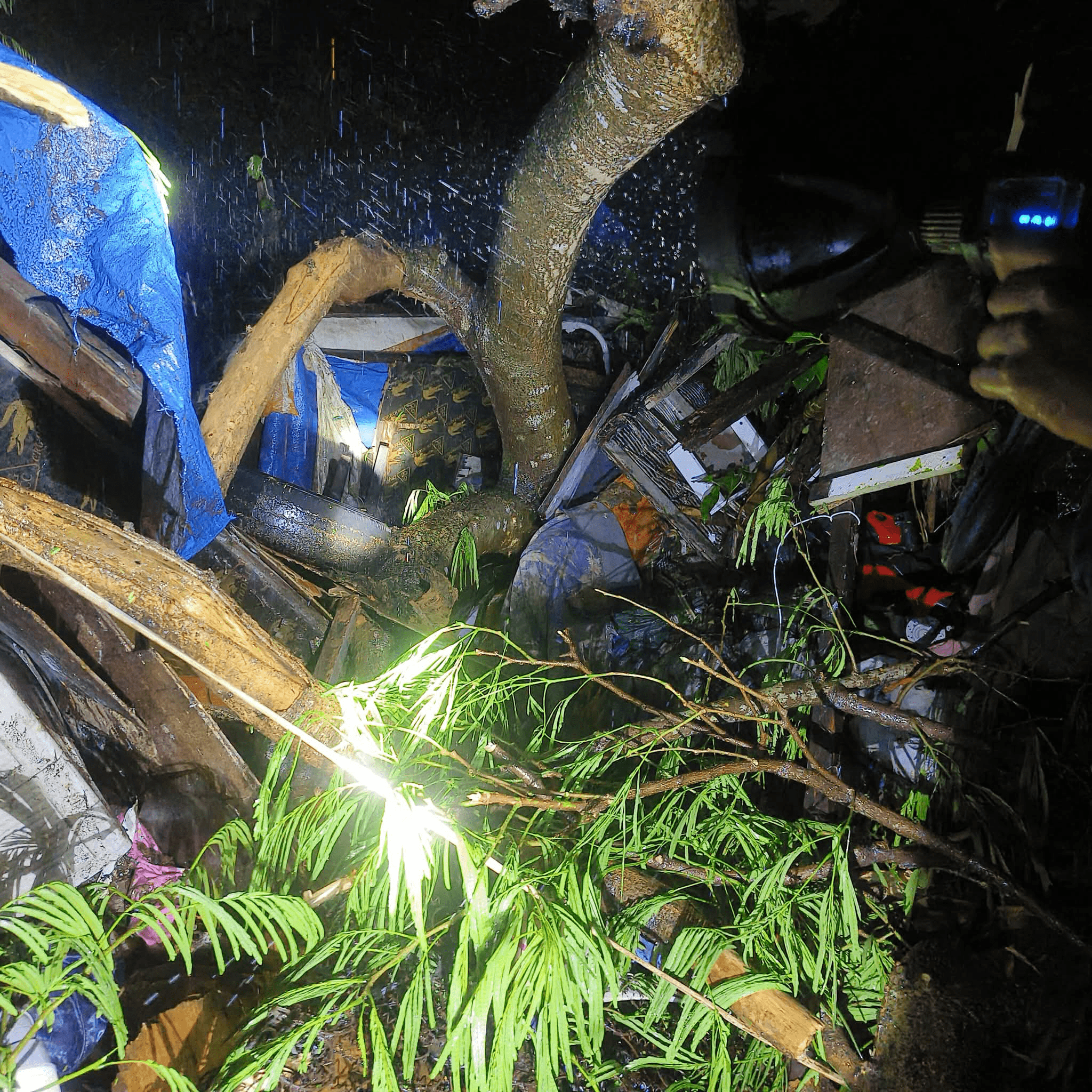

Despite the gains brought about by the courageous efforts of environmental defenders, environmental destruction by big corporations continues. The Mining Act of 1995 gave mining companies timber rights, which allowed them to cut down trees within their concessions. During the Arroyo administration, at least five timber license agreements were reinstated, rolling back the gains of previous years. Continued deforestation has driven out communities—especially indigenous peoples—from their lands, and has led to dire effects on the environment: soil erosion, flooding, destruction of habitats, and increased greenhouse gases, among others.

At 65, Oposa retired from the practice of law but continues to fight for the environment. He gives talks at international conferences to share how environmental advocacy can make a real difference. During the pandemic, he whiles away the time painting landscapes and seascapes.

He does not relish the spotlight. He claims that he was just a guy who wanted to tell a story, and he always knew he was involved in something bigger than himself. What spurred him on through the years was the thought of leaving his children with an apocalyptic wasteland. “It will be your generation’s world,” he told me. “It is time for the young generation to take up the baton.” ●

This article was originally published on August 24, 2020.