Prisoners encounter several problems for the duration of their confinement–congestion, slow-paced hearings, and health threats. Amid these issues, humanitarian advocates call for prompt action for the country’s thousands of detainees.

The 470 jails across the country only intend to hold 20,746 prisoners. In 2020, the inmate population hit 115,336, putting the average congestion rate of Philippine detention facilities at 403 percent, according to Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) data. These institutions are guarded by only 16,949 personnel.

The pandemic further magnified the dire condition of jails and inmates. Philippine jails were reported as the most congested prison system in the world, according to Raymund Narag, associate professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Southern Illinois University School of Justice and Public Safety.

“Prisons are not only full to the brim, [but] they are [also] teeming with emaciated and disease-carrying bodies,” wrote Narag in a Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) report in July 2018.

The jails’ severe overcrowding casts doubts on the capacity of the BJMP, Philippine National Police, and Bureau of Corrections to create measures in ensuring safer and more humane correctional facilities.

For instance, ideally, one prison officer should be handling only seven inmates. But, in reality, a jail guard handles 80 or, in worse cases, up to 300, according to Narag in a forum on prisoner welfare and jail conditions, organized by the PCIJ and the American Bar Association last November 15.

The snail-paced hearings are what primarily contributed to the issue of overcrowding, said Kenneth Guda, a reporting fellow of the PCIJ. More than 75 percent of the total detainees in the country are in the pretrial stage, having yet to be judged in the court of law and serve their prison sentence. The pretrial stage is where the accused states their plea of guilty or not guilty.

The protracted hearings are compounded by unoccupied courts, he said, adding that it takes about a year for a judge to be selected when the previous one has died, resigned, or retired.

Sky-High Congestion Rates

The assumption of Rodrigo Duterte as president in 2016 exacerbated the issue of congestion. With Duterte’s violent anti-narcotics campaign, 6,191 individuals have been killed, while 307,521 have been arrested, according to the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency in August 2021.

At the height of the Duterte administration’s drug war, the average congestion rates from 2016 to 2020 remained well above 400-percent overcrowding. This peaked in 2017, landing at 612 percent or 146,302 prisoner population.

In comparison, the congestion rate was 411 percent during the last year of former President Benigno Aquino III's term in 2015. While in 2016, it skyrocketed to 511 percent under Duterte.

“May tinatawag kami na ‘balagbag,’ yung natutulog sa sahig. Sardinas ka talaga. Ang pwesto mo lang, nakatagilid ka, hindi ka pwedeng humilata. Di ka pwedeng umunat ng katawan mo kasi masisipa mo yung nasa baba mo,” said a former detainee from Manila City Jail.

Much worse than the already serious humanitarian crisis of male prisoners, the struggles of women and juvenile detainees are exacerbated. More than overcrowding, these sectors face worse conditions in jails that give little to no regard for their additional needs.

Intensified Woes

Lactating mothers, for instance, lack stations where they can breastfeed their children, despite a law requiring lactation stations in all establishments or institutions. Minor detainees, on the other hand, confront issues concerning their psychological well-being.

In Taguig City Jail Female Dormitory, for instance, there is a 900-percent congestion rate, forcing some inmates to sleep in the hallways. The issue of overcrowding has also caused 63 inmates to use only two available toilets.

While laws to strengthen nutrition intervention programs for infants exist, like Kalusugan at Nutrisyon ng Mag-Nanay Act, such policies are rarely given regard in prisons. This issue was brought to light in October 2020, when the 3-month-old Baby River, was forcibly separated from her mother, activist Reina Mae Nasino, who was detained for trumped-up charges. River died less than two months after separation from her mother.

Despite representing only 2 to 10 percent of the total prison population, women also have additional necessities that need to be addressed, said Cham Perez of the Center for Women’s Resources. She noted that there is a lack of women-specific allocations in jails. Some would even refrain from changing their sanitary napkins and going to the restroom because of the shortage of pads and potable water.

Minor detainees, on the other hand, predominantly face the issue of deteriorating mental health. Children are often left to themselves with little to no psychological intervention during detainment, according to Ritchie Salgado, a Carmelite priest and reporter for Bulatlat.

“Putting children in shelters should be the last resort. Attention should be given to Bahay Pag-Asa centers, particularly in achieving restorative justice and rehabilitation of children,” he said. Bahay Pag-asa is an institution that intervenes and supports the rehabilitation of juvenile detainees.

A similar initiative is Bukang Liwayway, a minimum security camp for minors that intends to mediate the healing and reconciliation of juvenile offenders and the offended party. It follows a core program that assists in the healing of the juvenile detainee and its graduates can continue their education. Some nonprofit and nongovernment foundations give detained minors financial incentives and subsidies, granting juvenile detainees the opportunity to advance their education.

Moving Forward

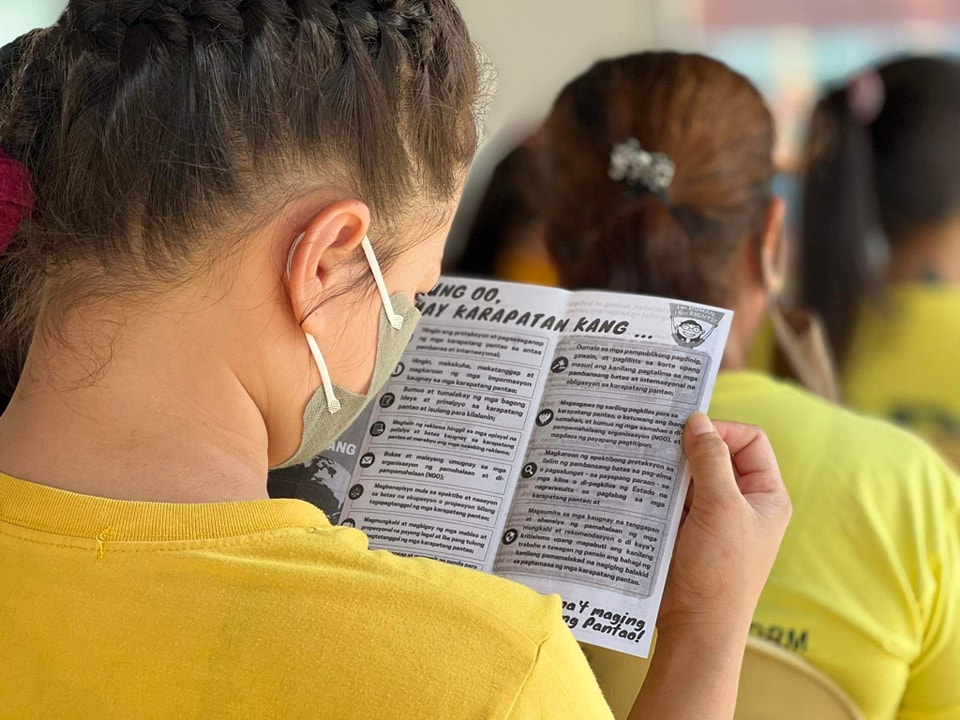

There are laws that protect prisoners’ rights. Some of them are the Bureau of Corrections Act of 2013 and the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006. The laws aim to provide subsidies to upgrade rehabilitation programs and prison facilities for detainees to reintegrate into society.

Nongovernment organizations have initiated programs geared toward helping prisoners. The College Education Behind Bars (CEBB), for instance, aims to provide the opportunity for incarcerated individuals to further their educational attainment while detained.

“They are more than what they have done so they should be given a second chance. Obstacles should be less, and opportunities should be more,” said Aland Mizell, founder of CEBB.

While efforts to support the reintegration of inmates into society are present, such interventions will remain inadequate if correctional institutions remain inhumane.

There have been calls to address the issue of overcrowding jails. For instance, there has been a call from Kapatid, an organization of friends and families of political prisoners, to mass release prisoners, considering the pandemic. Another is the law that allows the early release of prisoners for good behavior or the Good Conduct Time Allowance Law. However, such attempts remain overlooked.

Prisoners continue to amass in detention facilities as the justice system barely has progress in resolving cases because of the slow filling of vacant positions and lack of judges. Out of the 957 regional trial courts in the Philippines, 156 remain vacant or unorganized.

Offenders have the constitutional right to a speedy trial. However, laws that expedite the employment of judges are nowhere in sight as all judges are personally appointed by the president. But until bottlenecks in the judicial system remain, jails will continue to teem with prisoners who have yet to see a single day in court.

“Even in prison, one can find redemption,” said Amelia Cabasao, PCIJ reporting fellow. “Inmates deserve a second chance to be reintegrated into the community.” ●