Pook Marilag is the point of convergence for many dislocated residents from other communities within UP Diliman (UPD).

Three years ago, Marilyn Terinay’s family hastily constructed their home in Marilag after they were displaced from Village C by the campus administration to give way to the housing units that UP plans to build for its employees. Not far from the self-built units (SBU) of households like Terinay’s is a long line of identical single-story white houses occupied by the victims of a 2022 fire in Village A and C. Built by the Quezon City government, these transition units also house farmers like Antonio and Vilma Dizon, whose farmland was used as a site for these units.

The self-built units erected by Pook Marilag residents who migrated from Village C. (Luisa Elago/Philippine Collegian)

The self-built units erected by Pook Marilag residents who migrated from Village C. (Luisa Elago/Philippine Collegian)

With no end in sight, these residents find themselves suspended in a seemingly eternal limbo where the threat of displacement continues to haunt them. Concrete plans regarding their permanent resettlement area have yet to be given to transition housing residents. Meanwhile, the likes of Terinay lament the lack of security of tenure in their SBUs, their fates left at the behest of the administration that rarely heeds them and even threatened to demolish communities several times.

The precarious conditions befalling residents of Pook Marilag typify the problems that come with slum dwellings that persist on the national scale—an indictment of the government’s failed housing policy and lack of a comprehensive framework for the provision of adequate shelter among the urban poor.

Reason to Endure

Confronted by substandard housing that renders inhabitants vulnerable, and facing high costs of utilities and persistent threats of displacement, Pook Marilag residents continue to bear these conditions as impoverishment leaves them with no other choice but to remain in their communities.

Terinay was among the first residents who relocated from Village C to Marilag three years ago. Terinay’s family lived their whole life in Village C, but amid the pandemic in 2019, they were hurriedly asked to vacate the lands to be used for the construction of housing units that UP will rent to its faculty and research, extension, and professional staff.

Marilyn Terinay, 52, who lived all her life in Village C, was ordered by the university administration to relocate to Pook Marilag three years ago. (Luisa Elago/Philippine Collegian)

Marilyn Terinay, 52, who lived all her life in Village C, was ordered by the university administration to relocate to Pook Marilag three years ago. (Luisa Elago/Philippine Collegian)

Despite the administration’s insistence for their relocation, Terinay received no support from the university for their housing. She had to depend on her sister and take out loans, which until now are still yet to be repaid, to construct their home in Marilag. “Wala talaga akong [kabuhayan]. Namatayan kasi ako ng asawa, tapos dito namatayan din ako ng isang anak, kasagsagan ng pandemic,” she shared.

Terinay’s house in Marilag is made entirely out of wood, which induces their vulnerability during calamities. But residents who need to fortify their homes against heavy rains must first apply for a permit from the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Community Affairs, which takes at least a week to be processed. A 2016 memorandum even prohibits adding hollow blocks and rocks as materials for walls without a permit, forcing families like Terinay’s to endure leakages as typhoons come and go.

But Terinay continues to brave all these dire conditions. After all, the repercussions of having to start over outside UP portend a much more daunting prospect, faced with higher costs of land and housing constructions while they still have not recovered from their previous debts. This is a dilemma shared by those who were granted transition units by the QC government.

Vilma and Antonio Dizon are among the beneficiaries of the local government’s transition housing in Pook Marilag. They were able to get a temporary residence under the program because the land on which the units were built was previously Antonio’s farmland, which he was actively tilling until the construction of the transition homes. Now, Antonio only has his small parcel of agricultural land left at Hardin ng Rosas, QC.

Antonio Dizon, 68, is an urban farmer whose agricultural land in Marilag was used as the lot for the construction of the transition housing units. (Luisa Elago/Philippine Collegian)

Antonio Dizon, 68, is an urban farmer whose agricultural land in Marilag was used as the lot for the construction of the transition housing units. (Luisa Elago/Philippine Collegian)

The Dizons, along with those who lost their homes to the fire, are only temporary residents in their units. Although they do not have to pay rent, their water bills spike to as high as P1,900 monthly even when their supply barely pumps any water throughout the day. Without individual meters, shared connections lead to higher consumption concentrated in a single source, causing it to be charged with commercial rates that are more expensive than residential ones. As previous case studies from IBON Foundation affirmed, households who source their water from bulk connections spend more than those who have their own connections.

No clear plan regarding a more permanent residence has been given to them yet, but Vilma said they are bound to be resettled on a tenement building being constructed in QC which they would have to pay for through a monthly rent of around P800.

The uncertainty of housing plans and the consequent blows to their livelihood unnerve the Dizons. Ever since time immemorial, the Dizons have been devoted to their farm, having sustained themselves through it.

“Labintatlo kaming magsasaka, lahat halos naapektuhan. Kasi puro nandito lahat eh. Iyong mga bahay nila, nandito rin. Nawawala na [ang] sakahan, nawawala na pagkain namin, habang inuupahan pa namin ang mga bahay namin,” Antonio said upon finding out that even the tenement building for permanent relocation is poised to be constructed on another farmland that his other fellow farmers till.

Although heavily burdened by the circumstances in Marilag, residents’ preference to stay there also hinges on their livelihood being situated in the city. Terinay and other residents of Village C were once offered to relocate to Morong, Rizal, but declined due to the absence of work there. “Lumaban nga kami na ayaw talaga namin doon sa [Morong] kasi mahirap ang buhay. Eh iyong mga asawa rito, nandito nga ang trabaho,” said Terinay.

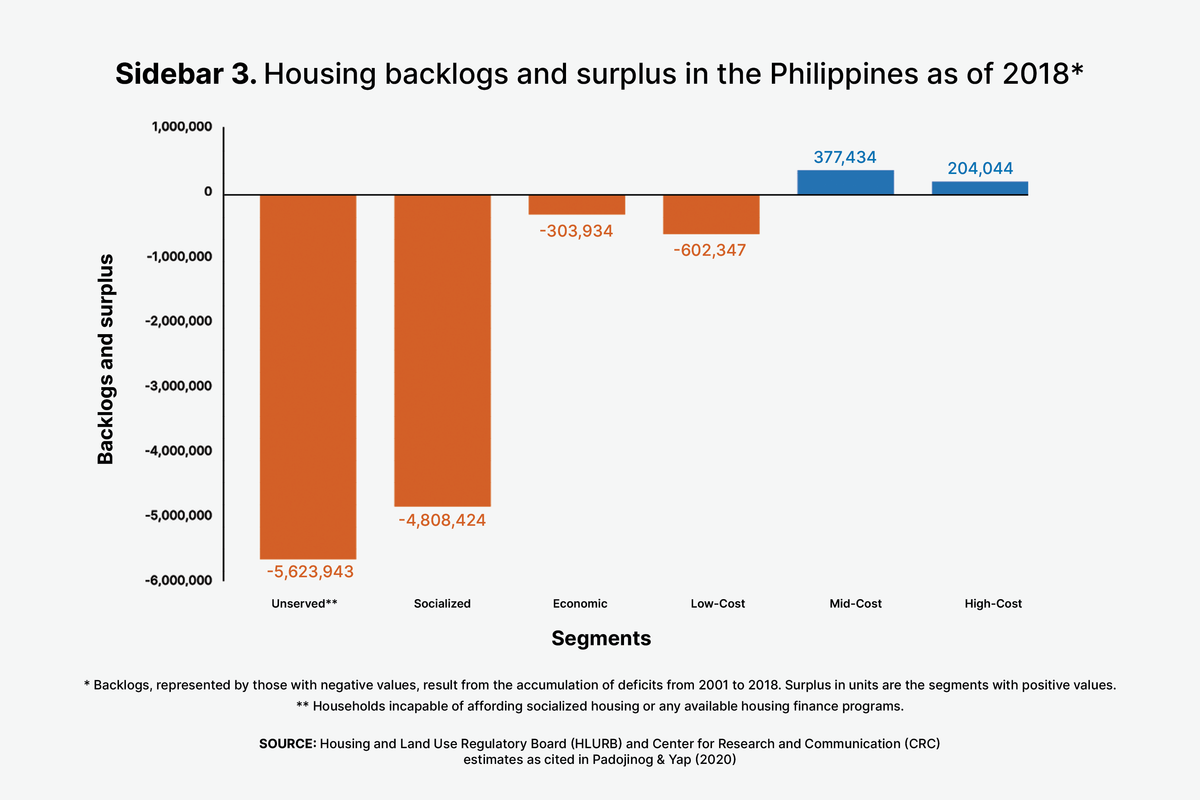

Once disconnected from a source of stable work, housing prices will only be more costly to the urban poor already struggling to make ends meet. Terinay and the Dizons are just a few among the 5.6 million Filipino households unserved by the government and housing market due to the unaffordability of shelters, according to a 2018 study by the Center for Research and Communication Foundation, Inc (CRC). These concerns on land, high costs of housing, and inaccessibility of livelihood that push people to refuse relocation are perennial issues that the urban poor in the nation suffer from.

Unending Exodus

Slum dwelling becomes the inevitable option for the urban poor as measures from the government persist to be lackluster, decoupling the housing problem with the larger context of socioeconomic precarity.

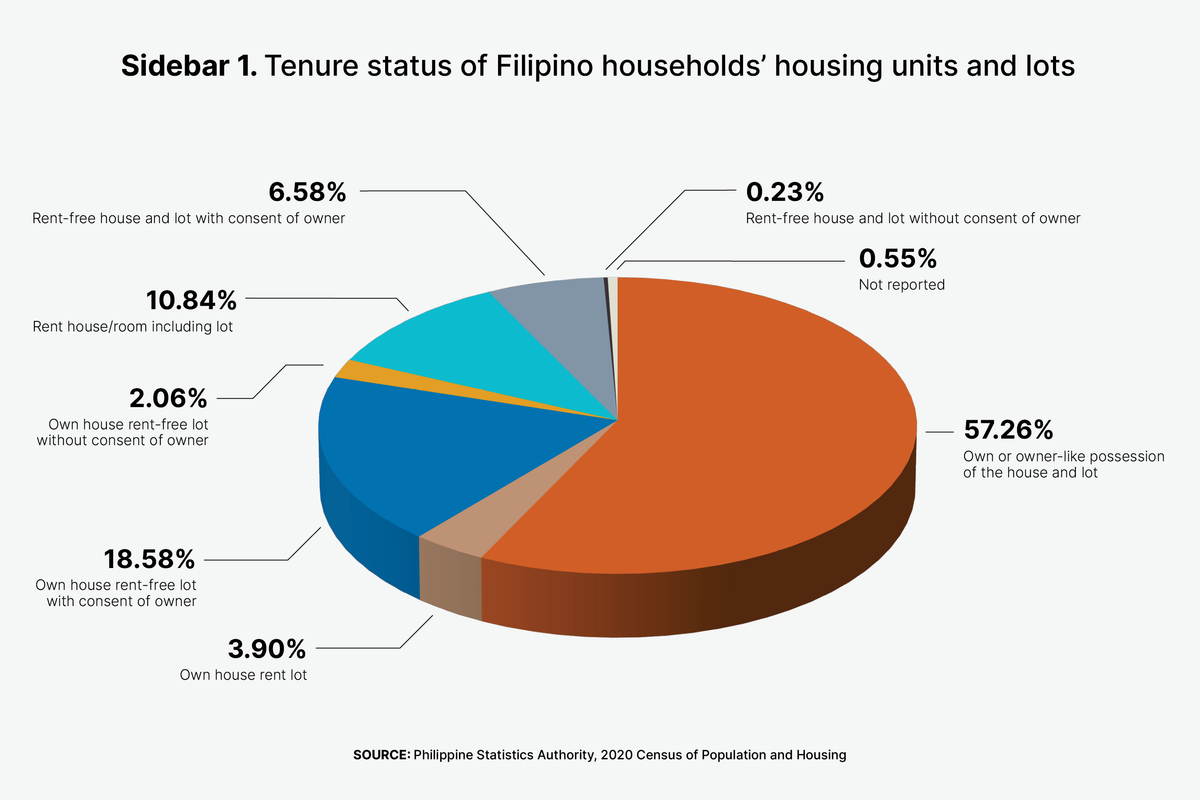

Residents of SBUs in Pook Marilag are part of the 43 percent of households with relatively less secure ownership rights of their house and lot (see sidebar 1), often at the precipice of being displaced. Once, UP President Angelo Jimenez said that he cannot “reconcile informal settlers in academic spaces.” By putting a rigid dichotomy between academic use and urban settlement, UP makes it appear as if a problem of congestion besets the university, resulting in a competition for spaces between academic stakeholders and community members. Thus, building housing units for employees necessarily entails the displacement of those dwelling in areas within UP.

Similar rhetoric is deployed in the justification of off-city resettlement—something that Marilag residents are all too familiar with, having been asked before to move to Morong. No matter the loss in livelihood and access to services, the government can rest easy knowing that it conveniently decongested the centers and instituted an expedient fix.

The problem, however, lies not in the saturation of the population. Only three percent of migration from 2013 to 2018 was from rural to urban, while the urban-to-urban and rural-to-rural moves made up approximately 93 percent of all internal migration, according to the 2018 National Migration Survey. Like Terinay whose entire family lived their entire life in the city, the figure indicates that the real issue is rooted in the state’s inability to promulgate an effective framework for inclusive urban development that provides a secure livelihood and housing for all. So long as employment is on shaky grounds, one will always transfer where there is more security.

Without enough income to expend on housing, people are driven to make do with what they have—to which informal settlement is sometimes where they resort to. Despite the latest labor force survey revealing that employment rose by 2.25 million, the largest increases come from subsectors with the lowest wages. This job insecurity paired with the increasing inaccessibility of houses due to privatization manifests into a housing crisis, Chester Arcilla, assistant professor at the College of Arts and Sciences in UP Manila, told the Collegian.

Since its creation in 1975, the National Housing Authority already posed to “promote private participation in housing ventures” through joint schemes with the private sector. This framework bled over to the passage of the Urban Development and Housing Act in 1992, where the state’s role was reduced to enabling the private sector to facilitate shelter financing of the urban poor instead of directly providing these services.

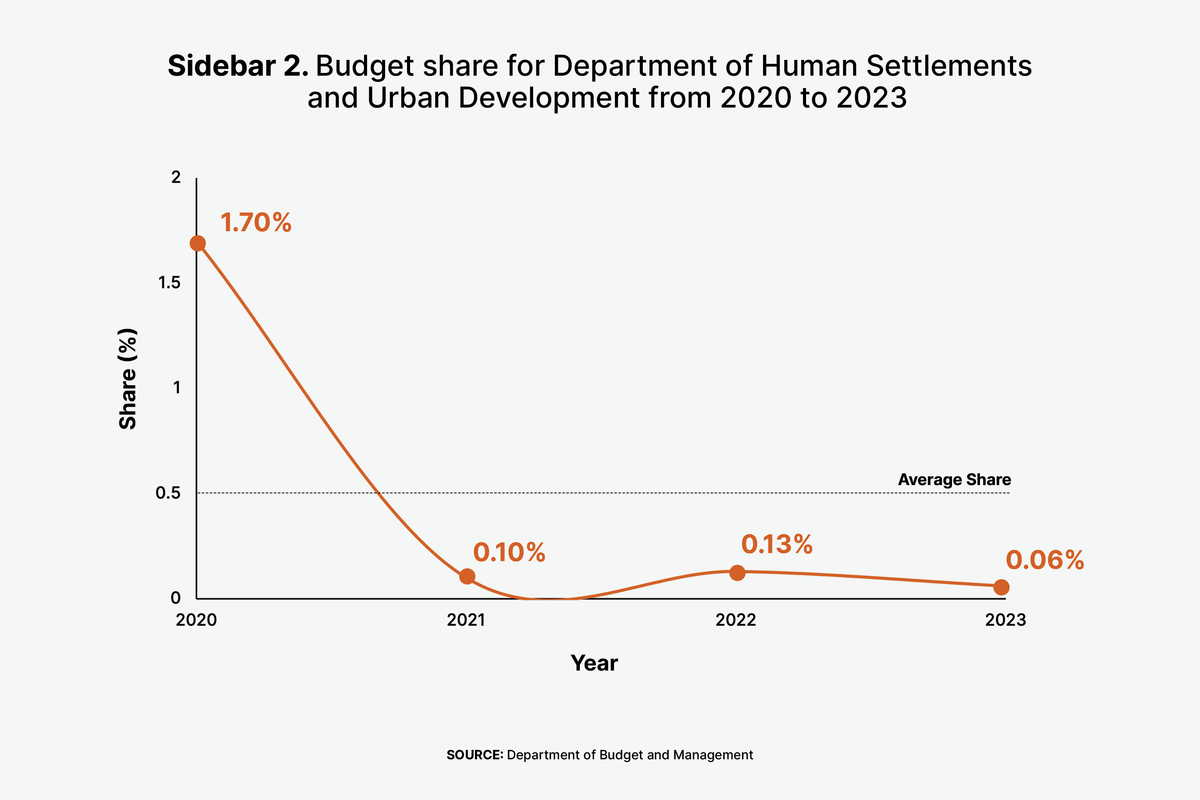

Yet even after the formation of the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development in 2019, the average allotted funds for its operations is no more than 0.50 percent of the national budget (see sidebar 2). The measly allocation is barely sufficient to help the 4.5 million homeless people or those in informal settlements recorded by the government in its latest data in 2018.

With socialized housing primarily run by private entities, the Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council permits contractors to charge residents for socialized housing units up to an overall P480,000 to P750,000. Given these costs, 31 percent of Filipino families do not have enough income to cover their expenses for socialized housing and other expenditures for their necessities, according to a 2022 discussion paper published by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

This inaccessibility is proven with 46 percent of the 274,994 built socialized units in 2017 that remain unoccupied. Even among those who occupied the units in Metro Manila, a third of them eventually moved out after a couple of years, per a 2018 report by the National Anti-Poverty Commission.

This is a perennial concern as early resettlement sites have long been marred by their remoteness from working districts and services, leading to as high as 50 percent of people leaving their new units, as explained in a 2016 study by Toby Monsod, professor at UPD School of Economics. Not taking into account factors like livelihood access as long as there is readily available land to acquire is rooted in the developers’ need to implement cost-cutting measures for investors to get their return.

To further generate profit, many of the projects for construction starting in 2016 gravitated towards upper-class housing where returns are more feasible, according to CRC. Meanwhile, the deficit from 2001 to 2018 on the supply of socialized, economic, and low-cost housing already accumulated to 5.7 million units (see sidebar 3).

The poorest are not the only ones who are disenfranchised by the government’s overreliance on the market for its housing policy. Monsod found that even families with low and low-middle incomes do not have enough entry points to formal, market-based housing and financing options. As a result, they sometimes avail meagerly funded and limited services by the state originally intended for the poorest sectors. One such service is the community mortgage program meant to help informal settlers eventually own the lot they occupy.

Marcos Jr. carries over past administrations’ housing paradigm through his Pambansang Pabahay Para sa Pilipino, which he professed is bound to address the government’s 6.5 million housing backlog. But this only regurgitates the same failed policy of his predecessors, as the poorest sectors will still be incapable of affording the P4,000 monthly amortization plus around P2,000 additional costs. This is already 20 times more than the National Housing Authority’s P300 monthly amortization which only 22 percent of informal settlers are capable of paying, according to the Urban Poor Leaders Network.

Should this practice of merely building units without taking into account residents’ living conditions and financial capacities push through, the state will only see more households resorting to slum dwellings in cities where their livelihoods are situated.

A Stronger Foundation

A truly affordable housing program engenders a framework that is integrated with “national programs on urban land reform, public transport infrastructure, poverty reduction, agricultural development, and employment generation,” according to Arcilla. Resettlement efforts must be linked to a wider project for economic security for the marginalized.

Crucial to this pursuit is the resolution of the land problem that drives exorbitant costs hindering both the state and citizens to access lots. To this, Monsod recommends the implementation of reforms such as imposing guidelines to standardize land valuation. Arcilla also forwards the need to establish alternative tenure arrangements as part of a fair and holistic urban land reform program. This includes the implementation of public rental modes as temporary and immediate concessions while the state equitably distributes public lands in the longer term.

It is also pivotal to target supports that are geared towards securing property rights and public funds to expand access to services and amenities in cities, Monsod wrote. This is to resolve the problem of almost half of the households in the Philippines remaining in categories where they do not have complete ownership of their houses and lots yet, just as with the case of Marilag residents always at the brink of displacement with no legal claim over their lands.

To achieve this, household social assistance can be carried out through grants consisting of serviced land, whether or not they include a core house, home-improvement grants, and mechanisms enabling communities to purchase building supplies in large quantities and offer quality assurance.

The state must bolster its role in providing housing rather than simply delegating it to the private sector. To assist areas weathering the difficulties of urbanization, local governments need to have community development funds that have links to municipal councils and are funded by grants, local budgets, and community savings. A policy that underscores ownership points that the government should subsidize at least 70 percent of the cost of each household’s residence for poor and low-income families.

But securing housing upon relocation is not all it takes for adequate and secure shelter for the poor. As with the communities in UP and across the nation, resettlement efforts must always come with studies on the net incomes that each household will have on their new site, as well as the services that will be within their reach for their other necessities. Arcilla proposed the provision of income-based subsidies, a comprehensive poverty reduction program, a clear framework for employment generation, and the institutionalization of participatory governance.

“Socialized housing [must] become part of a more comprehensive poverty reduction program so that housing becomes a very critical component of poverty reduction. There has to be more democratic planning on the ground that involves the urban poor in terms of planning,” Arcilla said.

UP, as a social critic and premiere knowledge producer of the nation, must appraise the informal settlement problem within its confines in this consultative approach and herald a model to the national government.

For those who converged in Marilag, it is in their earnest hope to never have to depart again. As the likes of Terinay and the Dizons continue to long for permanence in their residence, the state must secure residents’ right to be emancipated from their precarious limbo through a housing program that comprehensively addresses the interlocking facets of the urban poor’s struggles. ●