Update, 10/13/23: President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. signed a proclamation enumerating all the regular holidays and special nonworking days for 2024. The EDSA People Power Commemoration was omitted from the list. Malacañang, in a subsequent statement, said February 25, 2024 was not included in the proclamation because the occasion falls on a Sunday.

It is no secret that since his family’s ouster due to the people’s revolt in 1986, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. had always aimed for a political comeback. But his refusal to apologize for Martial Law's horrors–even tagging it as “Golden Years”–casts a shadow. Despite his assumption to the presidency, his unapologetic and revisionist stance only worsened through the years, leaving more victims yearning for justice.

Over half a century since Martial Law, the absence of genuine remorse and justice compounds the suffering of its victims, salting the wounds of those who perished and were victimized by the Marcoses' bloody regime. With Marcos Jr. continuing his father’s murderous legacy, justice becomes more far-fetched, but still an imperative, especially to the countless and nameless victims of Martial Law.

Remorse

The five decades of impunity show how the country’s political system remained a fertile ground for the Marcoses to continue avoiding accountability and even return to power. How Marcoses, their cronies, and cohorts evaded accountability, nearly half a century on, demonstrates a continuing historical injustice against the Filipino people.

Numerous countries have grappled with various historical injustices—the slave trade, segregation of Black communities in the US, and the removal of Aboriginal Australian children, for example. These injustices, tied to systemic discrimination and economic inequality, continue to victimize the said communities, leading ethicist Janna Thompson to argue in 2001 that it is the state's responsibility to take accountability due to the enduring impact on the succeeding generations.

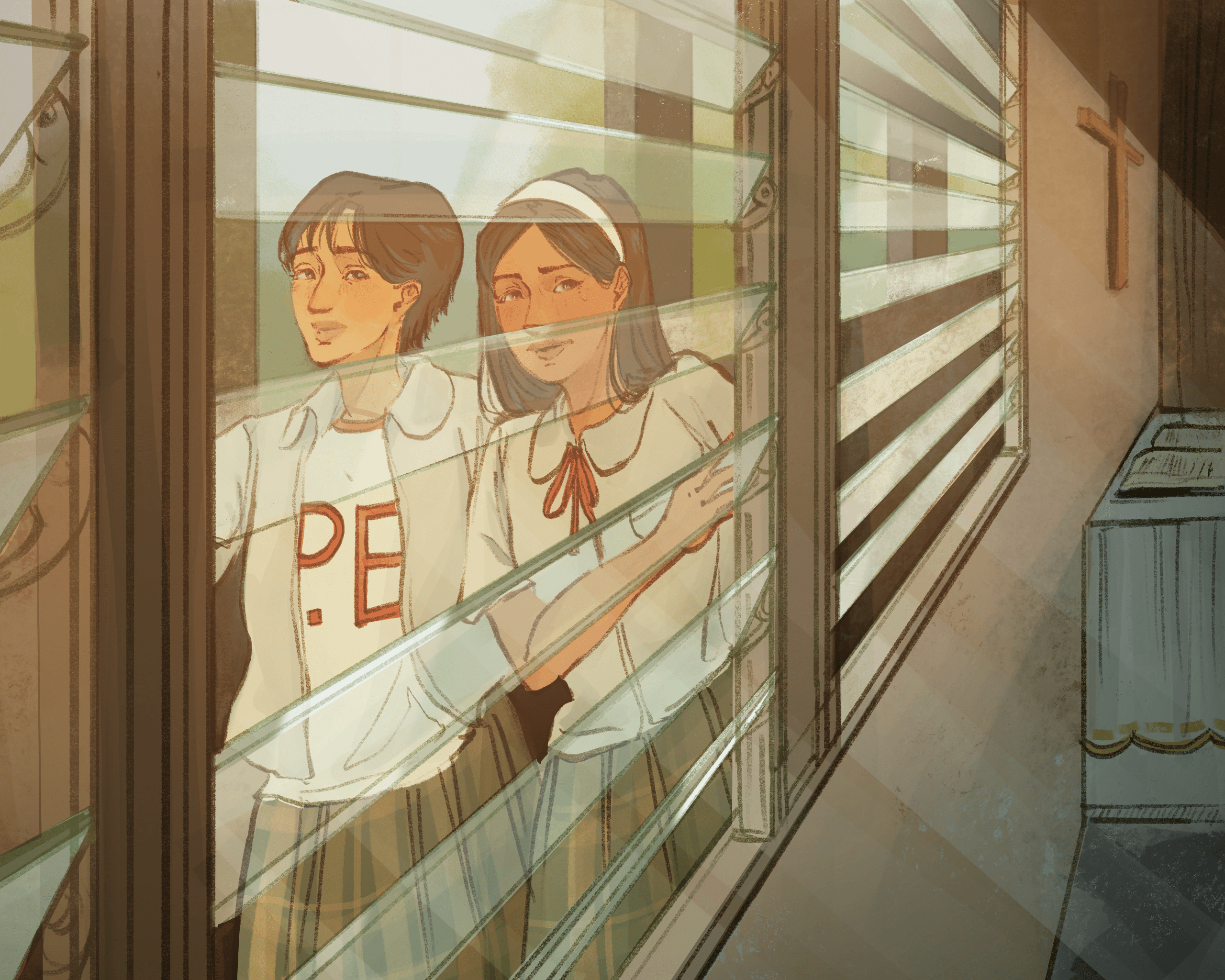

The scarcity of justice among Martial Law victims leaves an indelible mark. For most, it is a personal toll they have had to bear for decades. Families of desaparecidos remain uncertain about their kin's condition, although many of them remain hopeful. Survivors continue campaigning against the Marcoses’ return. For many, the wounds of Martial Law have been largely intergenerational because of the lack of justice.

For the thousands of Martial Law victims, the closest apology the state offered was the passage of the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013. While presented as an attempt at reconciliation, the law’s inadequacies–making the claims process a nightmare for its numerous documentary requirements–are heartless nonapologies, reflecting the state's reluctance to fully acknowledge its crimes.

Reparations

The dynamics behind an official, state-sanctioned apology is more comprehensive than the apologies we offer to another person. However, the effects of an apology become more essential when extended to a victimized group. A demand for an apology is consistently echoed by Martial Law survivors, including no less than Judy Taguiwalo, the former secretary of social and welfare development and convenor of the Campaign Against the Return of the Marcoses and Martial Law.

A group of political psychologists from the University of Waterloo in Canada reinforced this in a 2009 paper, arguing that an official apology fulfills important psychological needs of the victims, especially when the historical injustice happened for so long already. However, the effects of an apology are more political than personal.

For the nonvictimized majority, an official apology serves an educative purpose; teaching the harm of injustice, as theorized by Rhoda Howard-Hassmann, a Canadian academic and international human rights expert. In Australia, its Parliament’s apology to Aboriginal Australians led to the integration of the First Nations’ plight and suffering in the basic education curriculum, with the aim of “closing the gap” between the indigenous and nonindigenous populations. Unfortunately, the Philippines has not done so as it even distorted Martial Law lessons just last month.

A critical teaching of Martial Law atrocities in schools would expose the human rights abuses and their lingering impact on our present society. By fostering a more precise and empathetic depiction of the dictatorship, it can elevate awareness, exact justice and accountability, and play a role in rectifying historical injustices while also working toward eventual reconciliation.

Reconciliation

Because an official apology encompasses institutions of government, its effect becomes far-reaching. Singaporean philosopher Jennifer Mei Sze Ang, who studies the ethics of wars and conflicts, wrote in 2021 that a nation’s remembrance of injustice could prompt a state to initiate concrete acts to obtain justice for the victims; commemorations, appropriate revisions to written history and reparations.

On the surface, commemorative activities like holidays seek to reinforce a nation’s remembrance of historic events. February 25, the day of the Marcoses’ ouster, is a public holiday. However, September 21, the day of the declaration of Martial Law, is not. Malacañang has consistently been mum on these events, especially since Marcos Jr. became president. The slow erasure of these commemorations inevitably whitewashes the history behind them, almost akin to forcing Filipinos to forget them altogether.

When we return to the injustice experienced by Martial Law victims, that means edifying the country’s remembrance of Martial Law history, and ensuring that no dictators can rewrite and take it away from the national psyche. This manifests in the truthful, accurate, and critical reading of our nation’s history that will begin from the grassroots–measures that continue to swell through community archives and Martial Law history fact-checking initiatives, among others.

It is through historical justice that we can begin correcting a decades-long historical injustice. However, such a notion of justice will never be achieved sans remorse and apology not just from the Marcoses, but also from the state itself—the very system that allowed those injustices to worsen due to historical denialism and revisionism. Justice means holding the Marcoses and state accountable for their atrocities, an apology is just the start. ●

First published in the October 10, 2023 print edition of the Collegian.