A revolution, they say, is not a dinner party. Nor, they say, will it be televised. Hardly is it ever said that too few revolutions take off in a lifetime to even begin to be neither of these things. Waging one takes time, building on gains in dribs and drabs rather than by leaps and bounds. Along the way, movements may simmer down or fizzle out. But often they are brought to heel by the state’s own terror machine, which, in the Philippines, constitutes counterinsurgency forces paid and tasked to divine shape-shifting enemies where there is none, to inflate paranoia about dissenters in a miasma of lies and conspiracy theories.

It is a classic trope of casting about all kinds of allegations, the better to cover all the bases, to anyone even remotely exercising their basic political rights. It is hit-and-miss, but mostly nine clear misses out of ten cheap shots. Still, no matter how much we have tired of hearing officials red-tag even wholesome personalities, how ridiculous and routine all this has been, our own instinctive shock surprises us.

To maintain this capacity for outrage is to challenge pervasive dishonesty. The Duterte administration is, of course, hardly the first to portray communists as an unambiguous evil, as a singular threat to public safety. But the way it employs its networks and instrumentalities, at all levels of governance, to form the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), has so far made the most detrimental mockery of our democratic norms, with consequences far-reaching and even deadly.

The motivation for creating the NTF-ELCAC, as laid out in Duterte’s Executive Order No. 70 in December 2018, is the whole-of-nation approach, the full-blown, concerted project to stamp out Asia’s longest-running insurgency. This marks a sharp break with the president’s predecessors’ predominantly militaristic offensives against rebels, which, to be sure, have still not let up in the countryside. But fascist overtures percolating through broader public discourse have, in concert, lately heightened manifold, in the form of witch-hunts, propaganda, and wholesale vilification not just of activists but of critics, too.

The tactic is combative, hysterical, and exorbitantly expensive. The proposed budget for the NTF-ELCAC for 2021 soared, from its P622.3 million appropriation in 2020, to P19.3 billion. This skyrocketing budget boost is justified as lump-sum funds, not unlike congressional pork barrel, under the president’s Local Government Support Fund. The NTF-ELCAC, as a de facto secretariat, will disburse the biggest slice of the fund, like a finder’s fee, to some 840 villages allegedly cleansed of New People’s Army rebels.

National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon, Jr., who is the vice chair of the NTF-ELCAC, sounds the alarm on insurgents who he says maintain a stronghold in over 2,700 villages across the country. They deserve the rest of the task force’s budget, he says. Bankrolling such thinly veiled state-backed violence will meanwhile mean siphoning funds from what could be additional spending for, say, protective services for individuals and families in difficult circumstances—a social protection measure set to receive only P12 billion in 2021—or assistance to indigent patients that has been allotted only P17.3 billion, on the heels of a pandemic that not even Duterte can promise will have blown over by next year.

Esperon said in a speech in January that the proposed bounty-like budget for counterinsurgency would go to so-called development interventions in areas supposedly impoverished and pillaged by guerillas. This is twisted. Not only are Maoist rebels ideologically averse to such excesses, they have also only been documented to seize guns and munitions that might otherwise be used for the state’s own military adventurism. It is, in fact, the government’s lavish spending that needs to be reined in and accounted for.

No less than the Commission on Audit (COA) mulls a special audit of the NTF-ELCAC’s budget in previous years. “So it’s something that we have to look at carefully because the amount of money involved is not typical,” COA Chairperson Michael Aguinaldo said during a budget hearing in September. “You have this task force involving different departments. Those are issues that will really be looked at.”

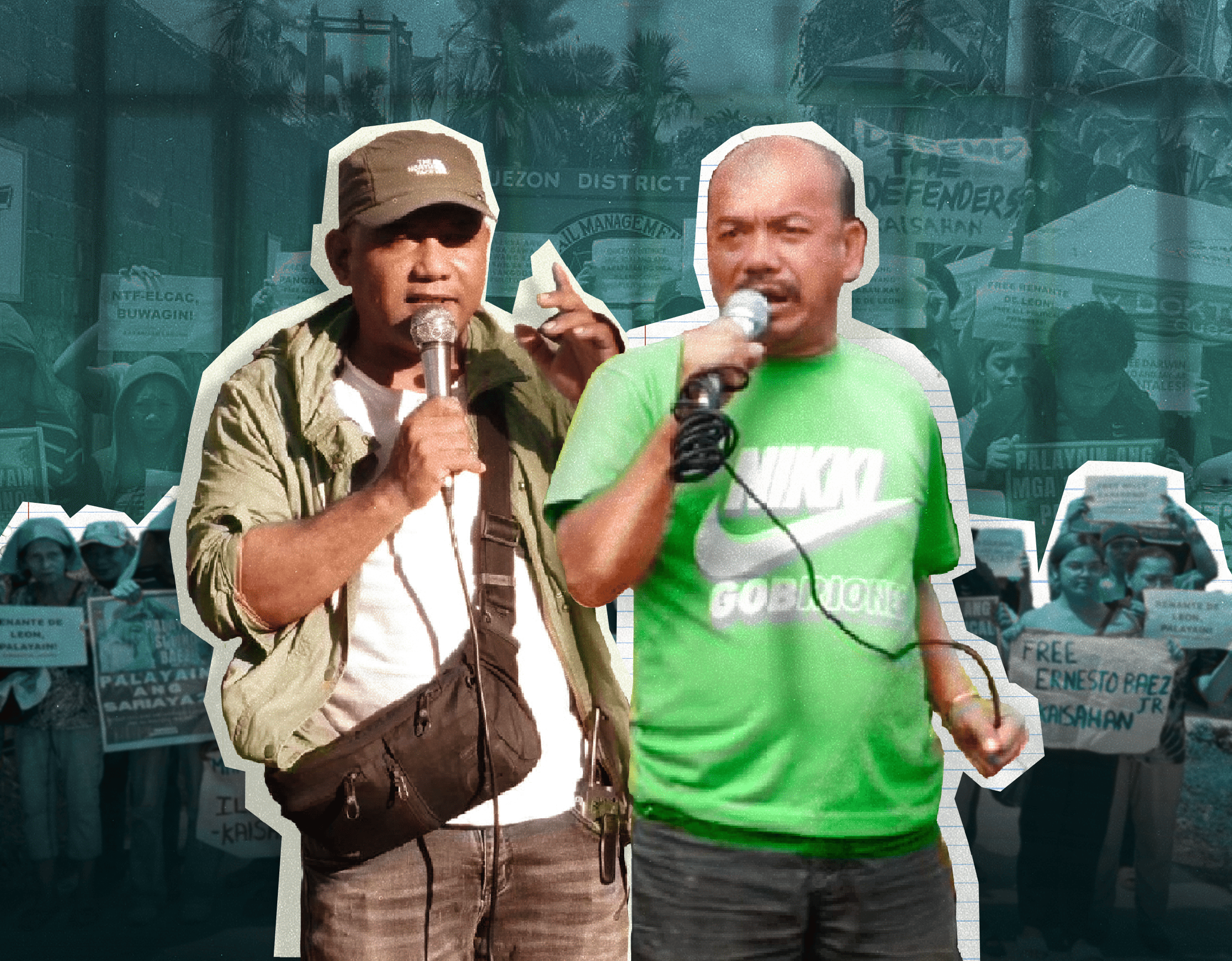

The most the task force could seem to show for its pricey efforts are, among other political gimmicks, fabricated photos of alleged rebel surrenderees, televised appearances of the likes of Presidential Communications Undersecretary Lorraine Badoy red-tagging a progressive think-tank, a slew of illegal arrests of activists on trumped-up charges, and junkets to Belgium, Bosnia, and Switzerland to lobby for cutting what the government insists to be so-called communist legal fronts’ aboveground sources of support overseas.

An audit may shed some light on where the funds have gone, which the NTF-ELCAC can, however, so easily explain away with bloated line items and rote rituals of bureaucratic rationalization. It is a stride short of interrogating the necessity for a well-stocked cohort of fabulists intent on imperiling lives, on invigorating fringe groups’ vile tendencies to inspire fear, to polarize the public, to isolate and target.

The call to defund the state’s counterinsurgency program, for one, acknowledges other budget priorities that have been proven more deserving of robust resources, more beneficial to underserved communities, than grasping at shadows for perceived threats. It also makes a case for an overdue pivot away from state violence in the long run. It captures how counterterrorism has only historically made a terrorist of the state itself, the only logical response to which is legitimate dissent that may be anything but peaceful.

We may not witness a revolution in this lifetime, but the least we can do is pave the way for one, whether that means dismantling a policy hostile to change or reimagining a society purged of a legacy of terror. ●

The article was first published online on October 30, 2020.