The government’s pandemic response fails in more ways than what is obvious. Non-COVID patients, in particular, are bearing the brunt of lockdowns and surges as the focus of policies and services has mainly been on the victims of the virus, limiting the rest of the population’s access to healthcare services.

As of April 29, the Department of Health (DOH) has registered more than 69,000 active COVID-19 cases in the country, making the total number of confirmed cases since the start of the pandemic 1,028,738, the second highest in Southeast Asia after Indonesia.

A huge bulk of these numbers can be attributed to the recent surge, which set the country’s highest record of COVID cases per day to 15,310 on April 2. This prompted the imposition of a two-week Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) in the NCR Plus bubble from March 29 to April 11. Currently, Metro Manila, Rizal, Bulacan, Laguna, and Cavite are now under modified ECQ until April 30.

The Philippine General Hospital (PGH), as the country’s biggest COVID referral center, is especially bursting at the seams due to the surge. Even after increasing the number of beds, the hospital still has close to 90 percent bed occupancy, with 30 intensive care unit beds always full, PGH Spokesperson Dr. Jonas Del Rosario told the Collegian.

Because hospitals are occupied by COVID patients, those suffering from non-COVID complications are left with little to no health care assistance.

“We have already instructed the public that we will be only admitting or entertaining real emergencies, whether COVID or non-COVID. Pero if you are a non-COVID patient at simple lang naman ang problema mo, hindi naman talaga emergency, then we will refuse admission,” Del Rosario said.

The impacts of the pandemic on non-COVID cases come as no surprise. However, under a pandemic response that the Duterte administration has described as “excellent,” the worsening tradeoffs in medical treatment for COVID and non-COVID patients should not be a picture still seen a year since the outbreak.

Health Tradeoffs

The pandemic has made medical treatments more difficult to access than they already are. To get her needed treatment, Loida Fernandez’s husband pushes her wheelchair forward, braving the six kilometers between their home in Batasan and the dialysis center in Fairview. They could not flag down any taxi or jeepney because, a month into the ECQ, then, no public transportation was in sight. They had to repeat this routine three times a week to complete her treatment.

Fernandez’s story could easily be mistaken as a recent event but actually, this was the scene that made headlines a year ago. Now, the situation has only become worse because, while she may have gotten the treatment she needed, albeit very inconveniently, many more non-COVID patients have not.

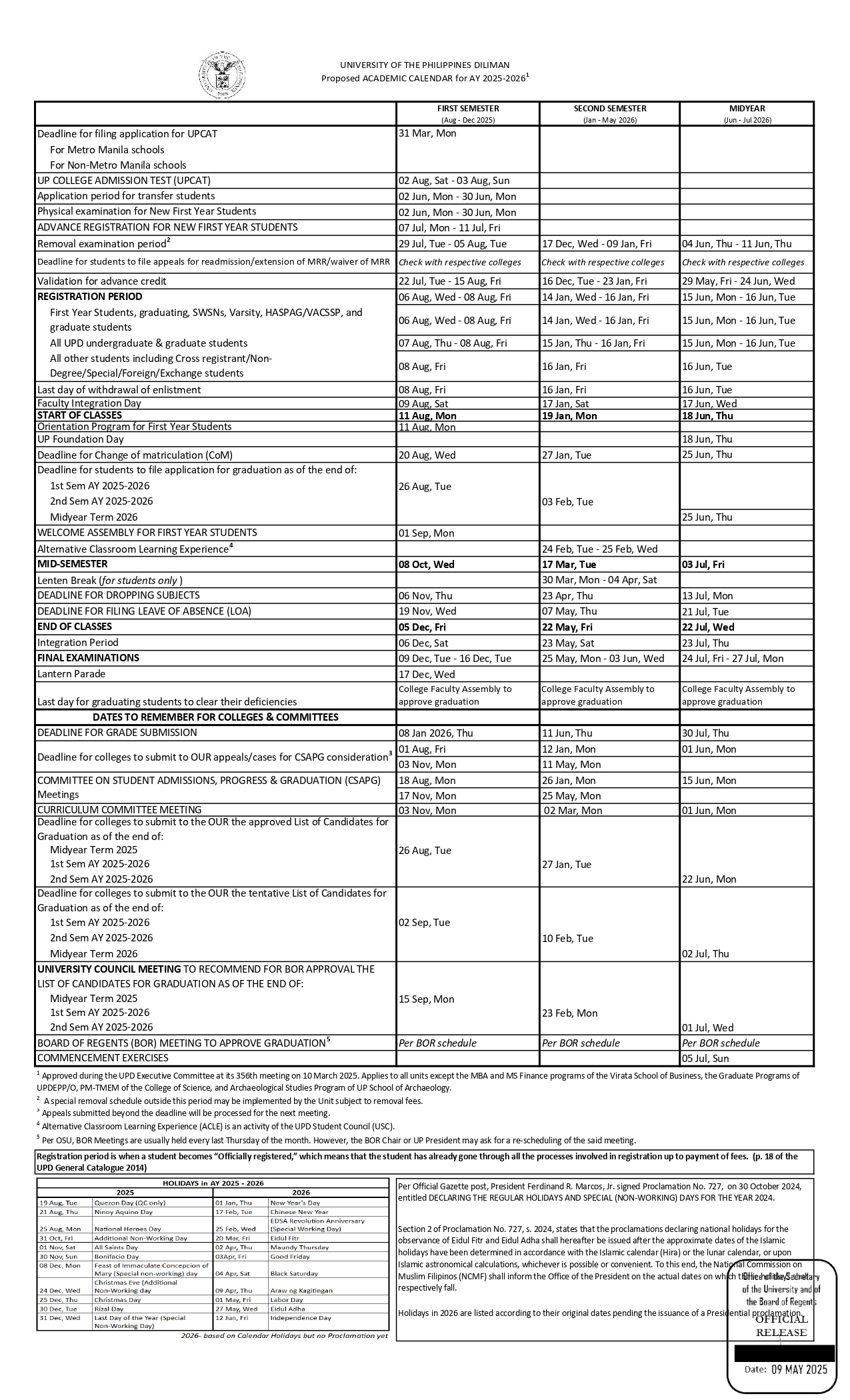

In fact, the number of claims for 12 diseases, which together comprise 50 percent of the country’s health disease burden, have declined since the start of the pandemic outbreak in the country (see infographic), according to the Center for Global Development (CGD), a think-tank. Disease burden is the total impact of a health problem on a country in terms of financial cost, morbidity, and mortality.

A team of researchers from the CGD led by Dr. Valerie Ulep, a research fellow at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, looked into the hidden health costs of the pandemic. They used the 2020 claims reimbursement data from the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (PhilHealth) to observe how the pandemic has affected the admission of non-COVID patients to hospitals.

PhilHealth is a government-owned and controlled agency that implements the country’s universal healthcare program. Its insurance program benefits about 90 percent of Filipinos, and almost all the hospitals in the country submit insurance claims to the agency.

Ulep’s team found out that the decrease in claims per disease during the pandemic had been steep, with the claims for eight diseases in particular—gastroenteritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, pneumonia, and tuberculosis—declining by more than 100 percent compared with 2018 and 2019 data (see Figure 2). Meanwhile, for stroke, cancer, dengue, and chronic kidney disease, the number of claims has also decreased, although not as drastically as with other diseases.

While the decline may have been an expected outcome of the pandemic, it is unusual to have had no recovery in the number of claims as the number of COVID-19 cases decreased in the third and fourth quarters of the year. The possible reasons behind this are still to be studied intensively. Ulep pointed out that telemedicine may be one explanation for it, especially since the PhilHealth insurance does not pay for online consultations, but he stressed that there was still no evidence to back this hypothesis.

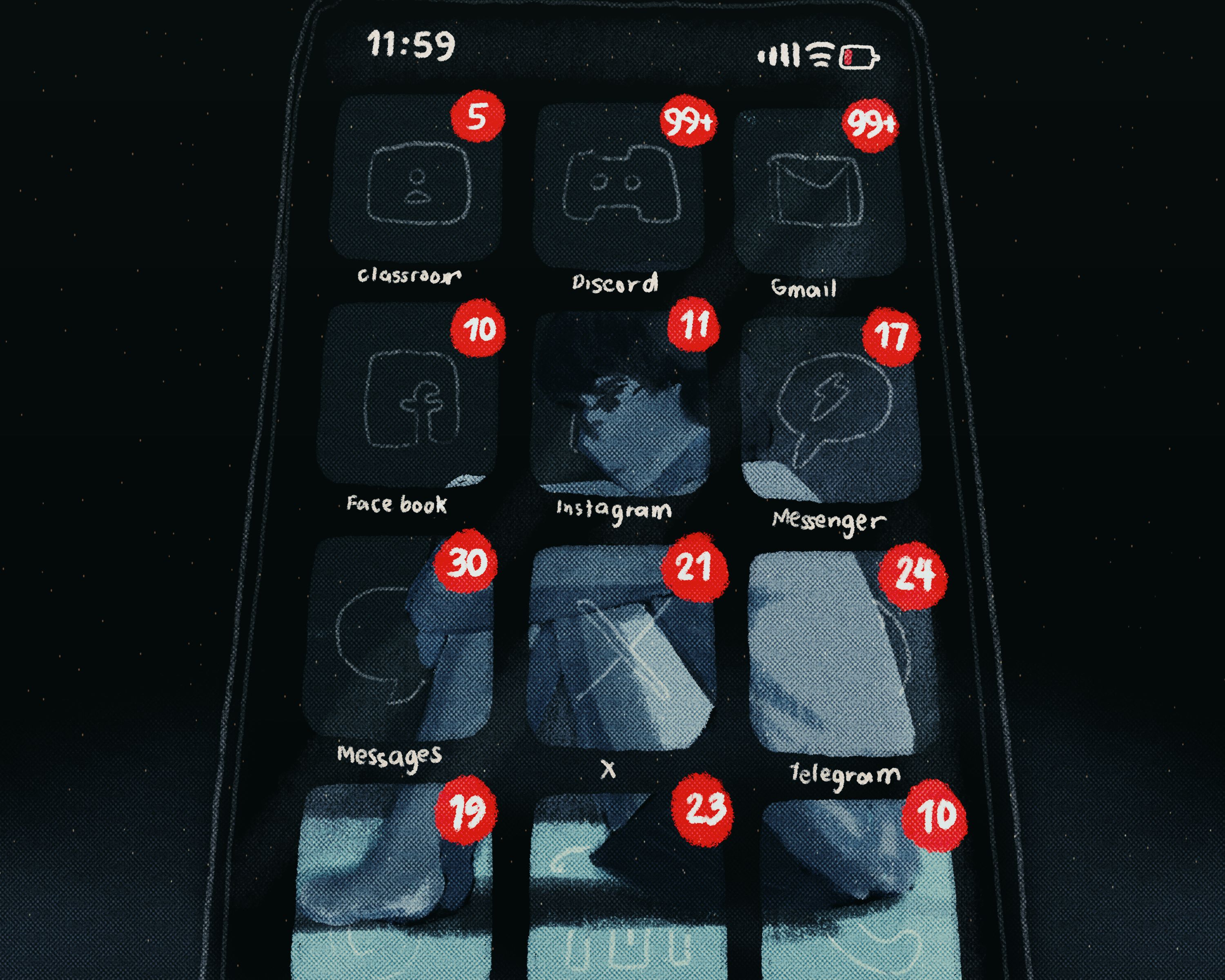

Some hospitals offer telemedicine as alternative health care assistance to cater to those who cannot be admitted. This is done through Viber, Messenger, or any messaging platform available. While it is an essential alternative during the pandemic, for Ulep, it would only increase the level of vulnerability of the patients since they would have to spend out-of-pocket money, which could have been used for food and medicine, to avail it.

In addition, according to former government adviser Dr. Tony Leachon, telemedicine may also pose difficulties for non-COVID patients. Older patients cannot easily navigate the gadgets and messaging applications needed for consultations. Some pharmacies also only recognize printed copies of prescriptions sent by text.

Of the decline in PhilHealth claims, Leachon said it would be hard to get to the bottom of these trends since even PhilHealth itself was undergoing some internal hurdles, what with the P15 billion corruption issue last year. He advised that a more comprehensive understanding of the trends might be obtained in six months or more, once the agency became more stable.

Meanwhile, in his analysis, Ulep found out that the more direct reasons behind the overall decline were the mobility restrictions due to quarantine, the lack of health care resources, and the fear of contracting the virus.

With the lack of public transportation during the quarantine, patients without private vehicles have to go through to get their needed treatment, as in the case of Fernandez.

Additionally, as hospitals are overwhelmed by the surge in COVID-19 cases, some of them, like the National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI), a medical specialty center for kidney-related issues, are limiting their dialysis operations due to the lack of manpower. According to Dr. Romina Danguilan, the head of the hemodialysis unit of the NKTI, the hospital had to close one ward and limit the allowable admissions in others because more health workers are needed to handle the COVID operations.

“The resources, including the manpower, of the hospital are diverted to COVID patients. Why? Because it's difficult to care for the COVID patients. You are at high risk maybe for developing COVID yourself. You cannot be wearing the personal protective equipment for a long time, you need rest time. So you need more teams to be assigned to the COVID wards because of these difficulties,” Danguilan told the Collegian.

For Ulep, looking into the indirect health costs of COVID would help policymakers to formulate a more holistic and calibrated pandemic response. “If you are only looking at one single number, which is deaths related to COVID or cases related to COVID, we do not come up with a more rational understanding of what the pandemic could actually do and we make irrational choices with regards to policy and how we should actually control it,” he said.

‘Healthcare Collapse’

In a report in 2020, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported ischemic heart diseases, neoplasms, and cerebrovascular diseases to be the leading causes of death among Filipinos that year, as in 2019. COVID-19 came in seventh and 16th for cases with the virus unidentified and identified, respectively.

This means that, even though the outbreak and surge of COVID-19 have alarmed the government and the public, as they should, health care assistance for non-COVID patients cannot be overlooked as the lack of such service continues to affect many Filipinos.

“You’re dealing with not only COVID cases but non-COVID cases. Because of the lack of medical check-ups, you have also a rise in patients with stroke, heart attack, advanced cancer, chronic lung disease, diabetes. Therefore, the hospital is filled up not only of COVID patients but also of non-COVID cases and this is a sign of an impending healthcare collapse when you have this kind of situation,” said Leachon.

If the neglect of non-COVID patients continues, the impact will not only be felt by individuals but by the entire country itself. According to Ulep, in the long run, if these cases are disregarded, they will only become more serious, which would make treating them more expensive and inaccessible, especially for the poor.

Wealth and access to health care are directly correlated. People who do not have enough resources to care for their sick family, or even to sustain themselves, will eventually have to go out and find a way to make ends meet, even if this means exposing themselves to the risk of COVID. This is the case for the 25 percent of households in NCR and Cebu who had a complete loss of income in September, based on the United Nations Development Programme Pulse Survey.

The intertwined effects of the pandemic on the economy and health leave the country stuck in a loop of surges and lockdowns, passing on the burden to patients and the health care workers manning hospitals.

“Here in the Philippines, they’re overworked, they’re overburdened, but they’re underpaid. Yan ang mabigat diyan e, di ba? Overworked, overburdened, and underpaid. So kung ikaw din ang health care worker, e, aalis ka talaga. You go to a country where your services will be more recognized despite the risks,” said Leachon, who had served as a special adviser to the national task force on COVID-19 before he left due allegedly to his “differences with DOH policies, e.g., lack of sense of urgency, problems in COVID data management, and transparency in communication process,” as he revealed in a tweet last June.

What Can Be Done?

The government’s inefficient pandemic response has passed the buck to medical institutions. Hospitals, especially specialist centers, have been implementing timely measures to make sure that they fulfill their responsibilities to their patients amid the surge and insufficient resources.

In the NKTI, for example, since the start of the lockdown, doctors and administrators witnessed an increase in the number of dialysis patients with COVID-19 as many were displaced from their original treatment centers, said Danguilan.

In her column for Business Mirror, Danguilan said that at the start of the pandemic, they expanded their Emergency Room facilities for around a hundred suspected COVID patients, ensuring that the main hospital focuses on deadly and highly infectious diseases. The NKTI also set up three tents with the needed machines to accommodate the increasing number of hemodialysis patients.

As a compromise, the NKTI does telemedicine for consultations, while for treatments, they had to reduce the frequency of the sessions to cater to more people. “If you would see the patient monthly before, now, you see them every three months. We try as much as possible if we can lengthen the duration of time that we see patients. So, in the interim, you have to resort to an online platform,” Danguilan told the Collegian.

Even with the prompt workarounds done by the NKTI to cushion the effects of the pandemic on non-COVID patients, still, the hospital has found itself in “crisis,” as described by Danguilan. This is because the question of how to solve the decline in the healthcare services for non-COVID patients is not one that exists separate from all the similarly systemic issues the country is facing.

“In order to prevent all these things, you have to decrease the number of cases to a volume less than a thousand, like before, para masabi mong okay,” Leachon said. Ultimately, it boils down to slowing the virus and providing the people with adequate resources to fight off the pandemic.

For Leachon, ECQ must be imposed together with mass testing and contact tracing. This would buy time to scale up the facilities and resources for hospitals, as well as give a timeout to the healthcare workers who have been tirelessly working since last year.

Unused academic institutions, hotels, and stadiums may also be transformed into makeshift hospitals so that more patients can be admitted. The whole medical community must be mobilized to man the operations in these hospitals, as well, Leachon added.

For Del Rosario, the government should see to it that non-COVID referral centers are being fully maximized so that the COVID referral centers like the PGH would not be overwhelmed. He also calls on the government to ensure that there is enough manpower in charge of different hospital operations, for COVID patients and otherwise.

“With the rate that we are going, we’re going to be overwhelmed. We will be short of our healthcare workers. Some of them are getting sick, some are just—they don’t just have enough numbers [relative] to the number of the patients coming in,” Del Rosario said.

The DOH allowed the PGH to hire doctors, nurses, nurse aides, and medical technologists after the hospital had asked for reinforcement from the agency on March 25.

Essentially, Del Rosario believes that the government should reconfigure the system such that it allows both non-COVID and COVID patients to be taken care of by hospitals of certain expertise and that there is enough manpower and resources for these hospitals to operate smoothly.

Meanwhile, for Ulep, the policy response of the government should be straightened out. Imposing lockdowns without making sure that there is enough provision for the poor would only be regressive. It would leave the poor with little access to food and resources, which would only make them more vulnerable to the pandemic. He believes that it is their duty as policymakers to balance the consequences of the pandemic to health and the economy, keeping in mind that these are two interlinked domains of a country.

The advice given by the three experts has been the same calls the public has been demanding since the start of the pandemic—mass testing, contact tracing, and aid from the government. Health care workers have also expressed the need for a timeout and pandemic measures that are scientific and data-based.

A year in lockdown should have given the government enough time to curb the virus or make strides in that direction, at least. Instead, the Philippines is, as Leachon describes it, “on the brink of a healthcare collapse”—back where it started, but enduring worse aftermaths across all sectors.

To put a stop to the pandemic, Ulep urges: “We need a more sustainable way of actually controlling this pandemic and thinking about not only the COVID patients but also the non-COVID ones.” ●