Gone are the days when fascists feigned a sense of common decency. They used to try refracting their violence and vulgarity through forced, though dishonest, discussions on the history of counterinsurgency. This, at the very least, fostered a conversation quite different in its language at face value, but not so much in its design any more than their naked redbaiting and hand-wringing of today are—the goal is, and has always been, to strike fear into the hearts of all but their allies’.

Once upon a time, in fact, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) wrote an open letter to the Philippine Collegian. An unknown man distributed copies of the letter on campus. “Demonstrators can continue to argue, oppose, or debate over the merits and demerits of policies, decisions, etc.—such are the works of democracy,” read part of the letter, which was later posted in full on the official AFP website, in 2008, signed by one Leopoldo D. Galon, Jr., commander of the AFP’s 7th Civil Relations Group. “Our premium concern is those who cross and double-cross the thresholds to armed struggle and illegality.”

The letter harped on the publication’s alleged role in propping communist fronts that masqueraded as legal organizations—it was “a gauntlet thrown at the Collegian and all it represents,” as the editors later wrote in response. In better times, the letter’s shoddiness, the absurdity of its arguments, would not deserve any smidgen of praise. But looking back on it now—when the president and his men are graded on a curve at the slightest hint of dignity—you could appreciate, if for nothing else, the military’s attempt to speak the language of its critics. You could sense its effort to sound sharp. You could go so far as to make out that one thing the military no longer accords journalists—respect, or semblance of it, at least.

Where, once, there was such an attempt to arrive at a public sphere—the discursive space, to borrow German philosopher Jürgen Habermas’ term, “in which political participation is enacted through the medium of talk”—the government’s foot soldiers could now only be bothered to bark and bully.

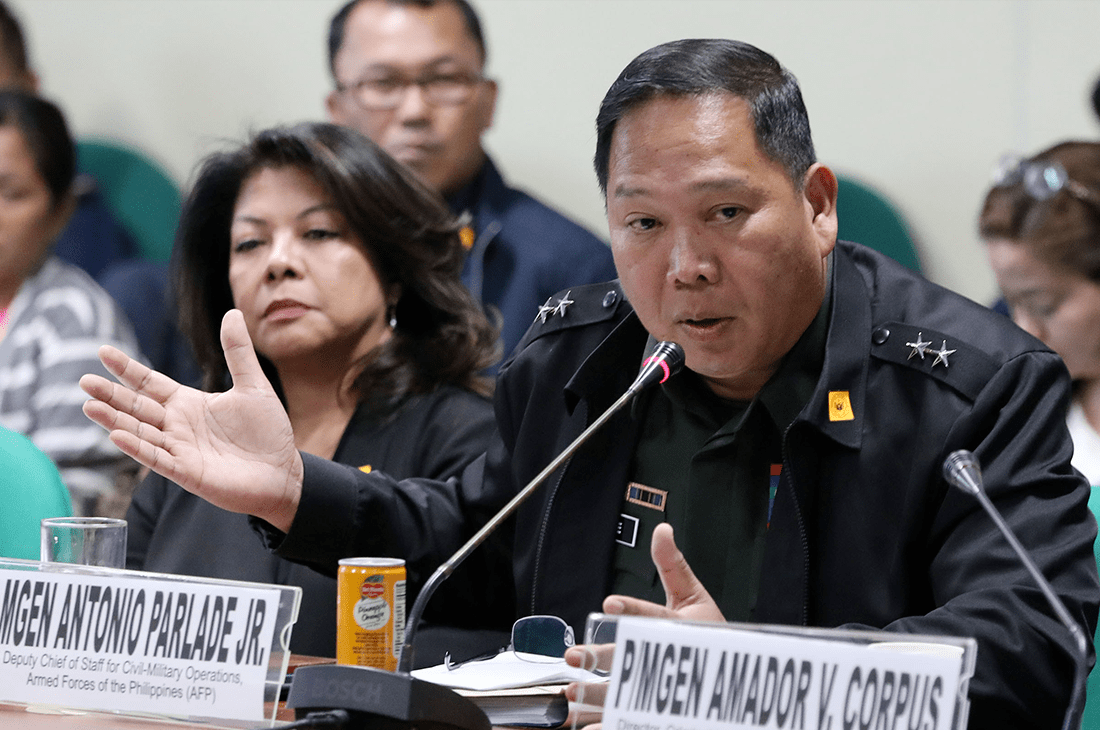

Slander is the province of the likes of Lieutenant General Antonio Parlade, Jr., the spokesperson of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC). Unsurprisingly, it is also practically what he accused Inquirer.net reporter Tetch Torres-Tupas of, after she wrote about the alleged torture of two Aeta men that the military had tagged as rebels. He hinted at filing a legal action against her in a comment on his Facebook post. In an interview on ANC’s “Headstart” last February 9, he later clarified it was only a possibility that he would not push through, anyhow. He then apologized to Tupas, if only for making her feel threatened.

It was, however, an apology only insofar as his colleagues, particularly AFP chief of staff, Lieutenant General Cirilito Sobejana, are presumably putting pressure on him to avoid burning any more bridges. Sobejana said he had asked the chief provost marshal to “find out if what General Parlade has been saying in public is with the committee’s blessing.” But he also said that Tupas bore the “burden of denial” to prove she was not “a propagandist,” like Parlade claimed, or a supporter of terrorists. Parlade, for his part, said his social media posts should by no means reflect the position of the agency for which he has actually been the strawman.

“I am speaking here as a citizen. I also have my rights to react to these false accusations by our media friends,” Parlade said in his interview. He described as “careless” Tupas’s report on the latest petition against the Anti-Terror Law. He took offense at its mention of how soldiers had reportedly forced the Aetas to eat human feces. “That’s very demeaning to our organization,” he said, “and to me personally.”

The general’s claim to fictitious victimhood brings us to a different level of crazy. He seizes on his right to expression—the very freedom he has, until now, brushed aside when equating outspoken personalities like Angel Locsin and Liza Soberano, to name a few, with communist sympathizers, or when endangering students’ lives by linking some 38 schools to supposed “recruitment havens” for the New People’s Army.

Parlade has proven himself as good as his words, which is to say not much. You could not but wonder if he even has a moral compass or, in any case, an elementary understanding of democracy. He is quick to use “citizen” and “rights,” but the spirit of these words hardly square with the fury of a tinfoil-hat know-it-all who is prone to conspiracy theories and alarmist ravings. His expression of hurt comes from the flip side of a universe that he and the rest of Duterte’s men inhabit, where they could pretend to be put-upon, denigrated by all those critical of them.

Yet it is one thing for Parlade to indulge in a fantasy of suffering, and quite another to impose it on the objective reality, to force the public at large to believe in his view of the world. It does more than just perpetuate an outlandish lie. His easily debunkable claims assert control of the public sphere in which, in truth, he never intends to engage with facts or acknowledge his position of power as anything but a God-given right to purge the country of communists. It is precisely this self-delusion that has, by now, distinguished the full range not just of Parlade’s depravities, but more so of the Duterte administration’s.

Besides, we cannot divorce Parlade from the president in whose image he has debased himself. For a second, though, it may be tempting to buy into his defense and think there is more to him than just the attack dog out on a weekly rampage. But a fascist cannot claim his status update and comment thread as his safe space. His social media persona—“the citizen Parlade,” he called it, and, by extension, all that he says on his platforms—carries the same weight and inflicts the same harm as Parlade the general.

Whether at a pulpit or from his desk in his office, Parlade can spew tirades to intimidate and instill fear, including by taunts, verbal slights, and veiled threats. He can hoist the banner of peace and order to rally people behind his trigger-happy assessments of our social corruption. When he gets called out, he has friends with guns and microphones to the rescue. “He’s being accused when, in fact, what he’s saying could be right,” Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana told CNN Philippines on February 8, arguing that, while Parlade may have gone overboard, “there’s a very thin line between freedom of expression and aiding the terrorist.”

That tightrope between truth-telling and terrorism, if we are to go by the government’s playbook, calls to mind “the thresholds to armed struggle and illegality,” as the AFP’s letter to the Collegian put it. Mangled, the metaphors bleed into one another, erasing the distinction between principled rebellion and a yearning for destruction, between accountability journalism and aiding and abetting. Words, thus mauled and cruelly deployed, can obfuscate substantive discourse, obstruct justice, and obliterate political communities.

Confronting the virulence of such language demands honesty about where we position ourselves in relation to history and power. The imagined common ground of civility no longer provides any point for departure toward progressive politics, and perhaps it never has, anyway, where tyrants and their sycophants are concerned. Gone are the days when we could still hope to get through to them by rhyme or reason, and perhaps that is just as well. We cannot, after all, build a common future with those who refuse to live in the same reality as ours. ●

The article was first published online on February 13, 2021.