When exploitation seems endless and justice only sides with the oppressors, the peasants fight back in the best way they know how: They till, plant, and struggle.

The farm workers of Hacienda Nene in Sagay City, Negros Occidental were all too familiar with this routine. Their decades-long battle for land ownership has taken them nowhere and their pay remained a measly P120 to 150 per day, which they do not even receive for all seven days of the week. And so, on October 20, 2018, the farmers did what they needed to survive. Along with the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW), they organized a bungkalan.

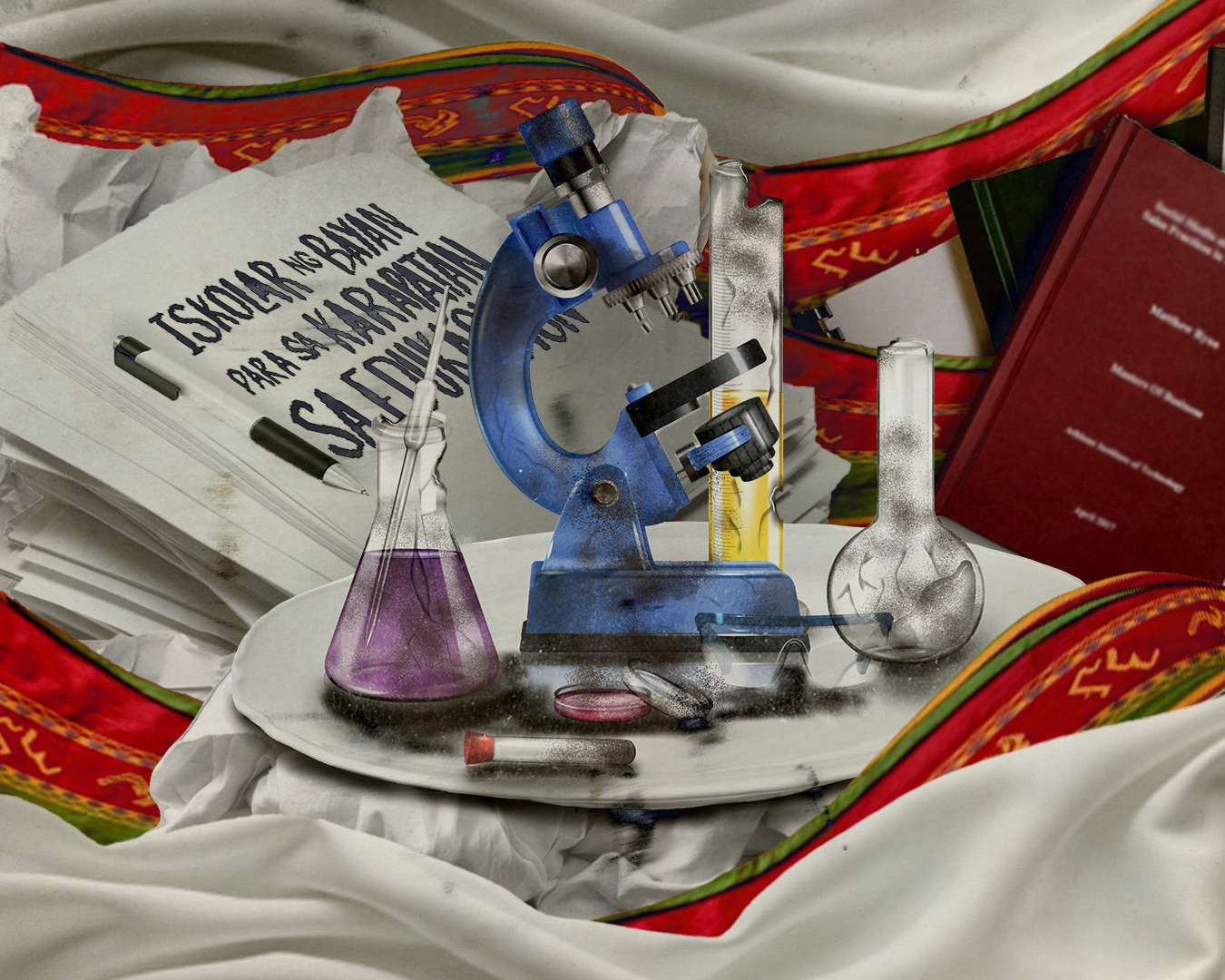

The peasants took over the lands they were barred from having. They took their tools to the farmlands, and cultivated and planted crops that would sustain them, contrary to the usual cash crops the landlords would make them sow. The bungkalan is both a plea and a protest.

But instead of finally getting heard, the Sagay farmers were met with terror and death as they were silenced in their own tents on the evening of the first day of bungkalan. Nine sugar farmers, dubbed Sagay 9, including four women and two minors, were killed in that massacre, and to this day, they still have not received justice—not for their murder, and certainly not for their plight.

Backed into a Corner

John Milton Lozande, secretary general of NFSW, was in Manila for a conference when the massacre happened. He had only heard of the brutal murder of his colleagues via phone call early the next day. “Nakapanlulumo na nakakagalit,” he recalled how he felt during the call. “Ganon ganon na lang ang ginawa sa kabila ng valid reasons at legitimate demands ng mga manggagawa sa hacienda.”

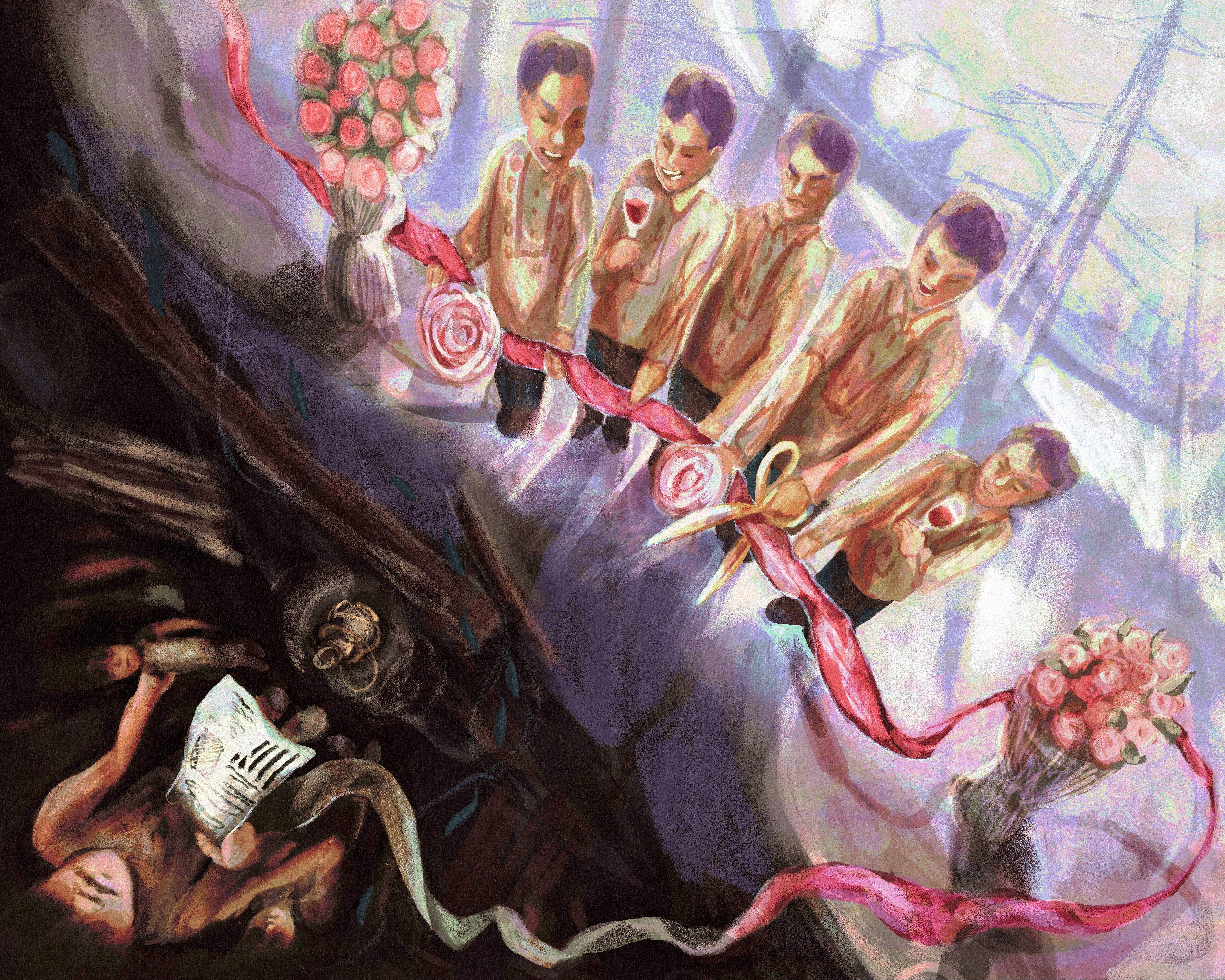

The workers in Sagay have long been fighting for the redistribution of the hacienda to its rightful owners. The birth of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) sowed hope for the workers in Hacienda Nene as the previous agrarian laws under the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. did not cover sugar land areas in the repartition.

Since 1988, the sugar workers have been relentless in applying to be land reform beneficiaries, but to no avail. They have had a total of three applications and three notices of coverage before 2018, all of which were denied by the Department of Agriculture (DAR) because there has been a deed of donation to 25 beneficiaries already.

However, according to NFSW, these donations were fabricated by the Tolentino family, the owners of the hacienda. The beneficiaries were their own family members, relatives, and close allies when the property should have been given to those who tilled the land.

Since having their 2014 application denied, the farm workers have organized dialogues with the provincial agrarian reform officer and held mobilizations in Sagay City. They have exhausted all means prescribed to them by the law. But the truth is, for the state, when it comes down to it, the peasant lands are just for grabs depending on who the highest bidder is.

With no other choice left, the farmers decided to occupy the land in resistance to the exploitative nature of the hacienda. The bungkalan also served to sustain them during the off-milling season in August, when there is no work in the hacienda, by providing them with sweet potatoes and bananas.

Out of the 77 hectares of the hacienda, they were only able to cultivate two hectares through the bungkalan—then the massacre happened. Forty unidentified gunmen showed up and killed the Sagay 9: Eglicerio Villegas, 36; Angelife Dumaguit Arsenal, 47; Paterno Baron, 48; Rene Laurencio Sr., 53; Morena Mendoza, 48; Marcelina Dumaguit, 60; Rommel Bantigue, 41; Jomarie Ughayon, 17; and Marchstil Sumicad, 17.

“Parang mga manok lang ang mga lumalaban para sa kanilang karapatan,” said Lozande, referring to how easy it is for the government to kill those who speak up. The nine farm workers murdered were only a few of the 344 victims of extrajudicial killings and of the 26 fatalities from massacres related to the peasantry since former President Rodrigo Duterte’s term in 2016, as recorded by the Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas.

“Isa sila sa mga naging casualty o biktima ng tinatawag [na operasyon] sa ngalan daw ng kapayapaan. Sinabi noong PNP chief, si Debold Sinas, para daw sa kapayapaan,” Lozande said. “Ito yung kapayapaan na sinasabi niya, may grabeng nangyaring patayan.”

Cycle of Life and Slavery

Four years since the massacre, the path to justice for Sagay 9 and all the land dispute killings remains bleak, but the peasants do not waver in making their calls heard.

“Sa totoo lang, wala namang option ang mga hacienda workers,” Lozande lamented. “Dalawang bagay lang naman ang nangyayari sa kanila: Tumindig sila sa kanilang karapatan sa lupa o yung cycle ng pagiging alipin sa lupa, bilang mga trabahador sa hacienda, yun na yung cycle ng kanilang pamumuhay.”

The hacienda system has had its chokehold on the peasantry since the Spanish colonization in the Philippines. To this day, even with all the past land reform programs, the landlord-tenant system of our agricultural lands has our farm workers remain oppressed by the rich and unprotected by the law.

The CARP has done nothing to help alleviate the status of the workers, not only in Hacienda Nene but in other farmlands all over the country. One could not forget the massacre in Hacienda Luisita that killed seven people, and injured hundreds of protesters who fought back when the Cojuangco-Aquino family refused to redistribute the farmlands despite the CARP.

After the massacre in Hacienda Nene, the corpses of the slain were kept at the city proper and the hacienda was cordoned and militarized to protect the undeserved properties of the Tolentino family. The workers’ union in the hacienda has also disbanded and the exploited families were silenced, either by money or by fear. “Siyempre, di mo naman masisisi sila kasi yun nga eh, yung buhay nila ang nakataya eh,” said Lozande.

For its part, the state has done nothing but weave its longstanding web of lies of peasant groups killing their own. The police filed murder charges against two NFSW officers, Rene Manlangit and Rogelio Arquillo, who were survivors of the massacre themselves. They were charged for allegedly putting the farmers in danger by bringing them to the bungkalan. To this day, they remain in hiding, not because of the fear of the charges but because they did not know who was still out to get them.

Since then, there were no more hearings and subpoenas on the case to the knowledge of Lozande. But for as long as the landlords are not made to answer for their actions, the true perpetrators remain at large.

The Bungkalan Lives On

After the gruesome experience of the peasantry under Duterte and the administrations before him, things are not looking up as the new leaders are nothing but old surnames in the government. Under the term of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., NFSW does not expect much as there are still no talks of implementing a genuine agrarian reform program.

This program has been the subject of the peasant’s calls for years now. “Ito yung pinakasentro ng [mga kahingian] ng mga manggagawa sa agrikultura: yung land reform program, yung [sapat na] sahod, at yung pagrespeto sa karapatan sa kanilang pag-organisa,” said Lozande. “Itigil ang walang habas na pamamaslang na ginagawa hindi lamang ng mga malalaking panginoong may lupa, pati na rin ng estado.”

Along with these calls to the government, the peasant community also mobilizes itself to ensure that their needs are met. In 2018, there were bungkalan activities in 145 areas in Negros. Hacienda workers and farmers, along with progressive groups, have won over 4,000 hectares of land from that. Peasant activists also continue to walk the streets and cultivate lands to fight for their rights.

Because of this, Lozande remains strong in his resolve to keep on fighting even with the seemingly far-fetched justice for peasants. “May katapusan naman itong mga karahasan na nangyayari. Hindi naman sa lahat ng panahon [ay] mangingibabaw yung mga kasamaan na ginagawa ng mga naghaharing uri, at mismo ng estado na nagrerepresenta sa malalaking tao na ito,” he said.

Hacienda Nene is not a lost cause. So long as the peasantry is not free from the chains of the hacienda system, the bungkalan continues to live on—in the soils of our farmlands, and in the hearts of the masses. ●