Filipinos are bearing the brunt of soaring food prices and a worsening hunger situation nearly a year after the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown was imposed. An estimated four million families experienced involuntary hunger—or hunger due to lack of food to eat—at least once in the past three months, based on a Social Weather Stations report published in December 2020.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the consecutive devastating typhoons in the past months are merely aggravating events, because the fundamental causes of the current crisis are decades-long government neglect and low prioritization of the agricultural sector, according to peasant groups.

“Nagpatong-patong na iyong mga problema at ngayon nararamdaman natin na ang mga tagapaglikha ng pagkain, sila iyong mismong kulang o halos walang makain. Habang ang mga mamamayan na kumakain o kumukunsumo ay nasa matinding kahirapan to access these food items lalo pa noong panahon ng pandemya na milyon ang nawalan ng trabaho,” said former Anakpawis Party-list Representative Ariel Casilao.

Further pushing the hungriest Filipinos to the wall, food prices continue to rise. The country’s inflation rate surged to 4.7 percent in February, from 4.2 percent a month earlier, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported. This is the highest record since the 4.4-percent inflation rate in January 2019 and the fifth consecutive month of surge in rate.

The increase is mainly driven by higher food prices, particularly of pork, according to the PSA. The continuous rise of food prices limits the purchasing power of Filipinos, especially those who lost their jobs during the pandemic, making it difficult for them to even sustain three square meals a day, Casilao said.

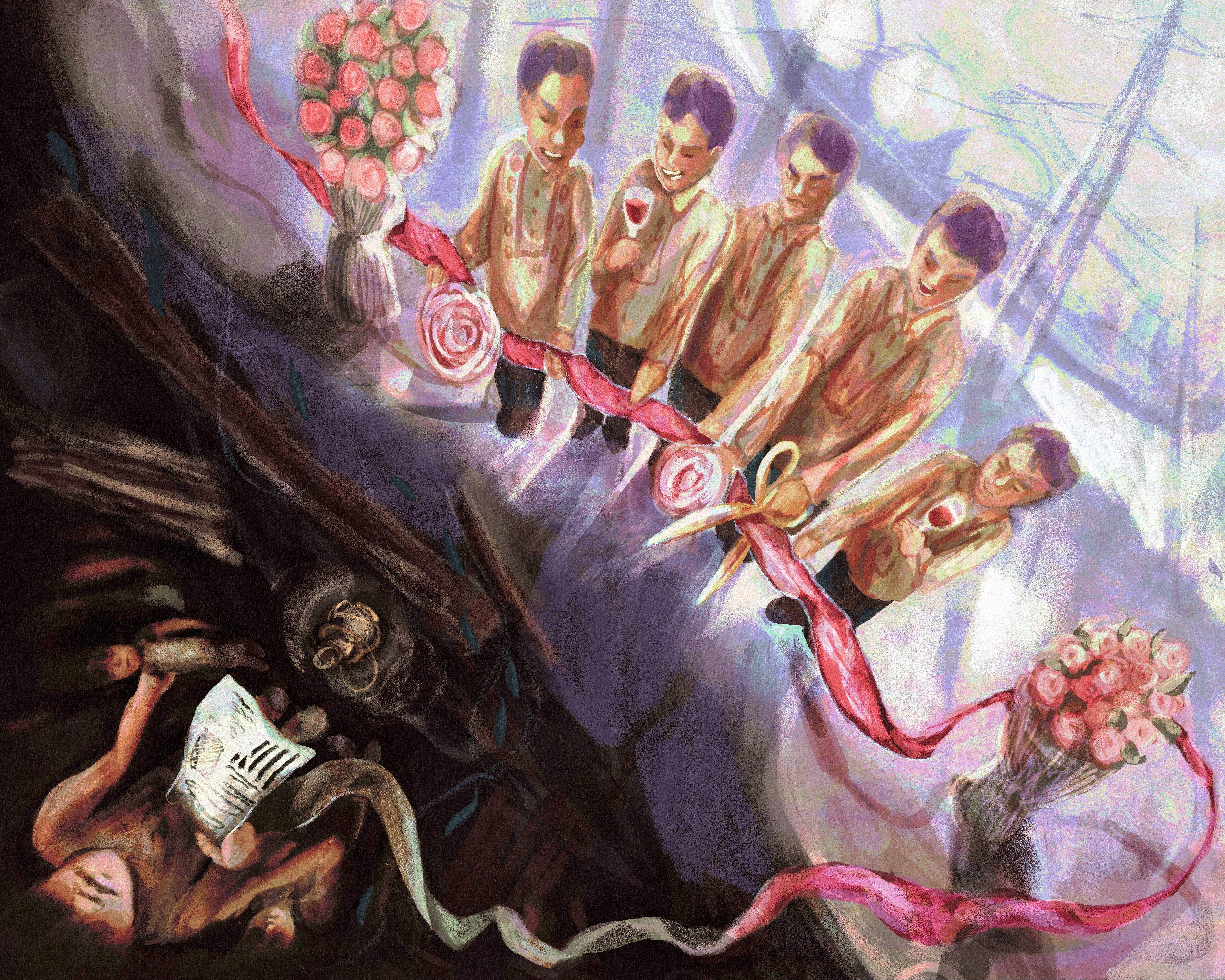

In an effort to attain food security and improve nutrition, President Rodrigo Duterte created the Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF) on Zero Hunger, headed by Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles, in January 2020.

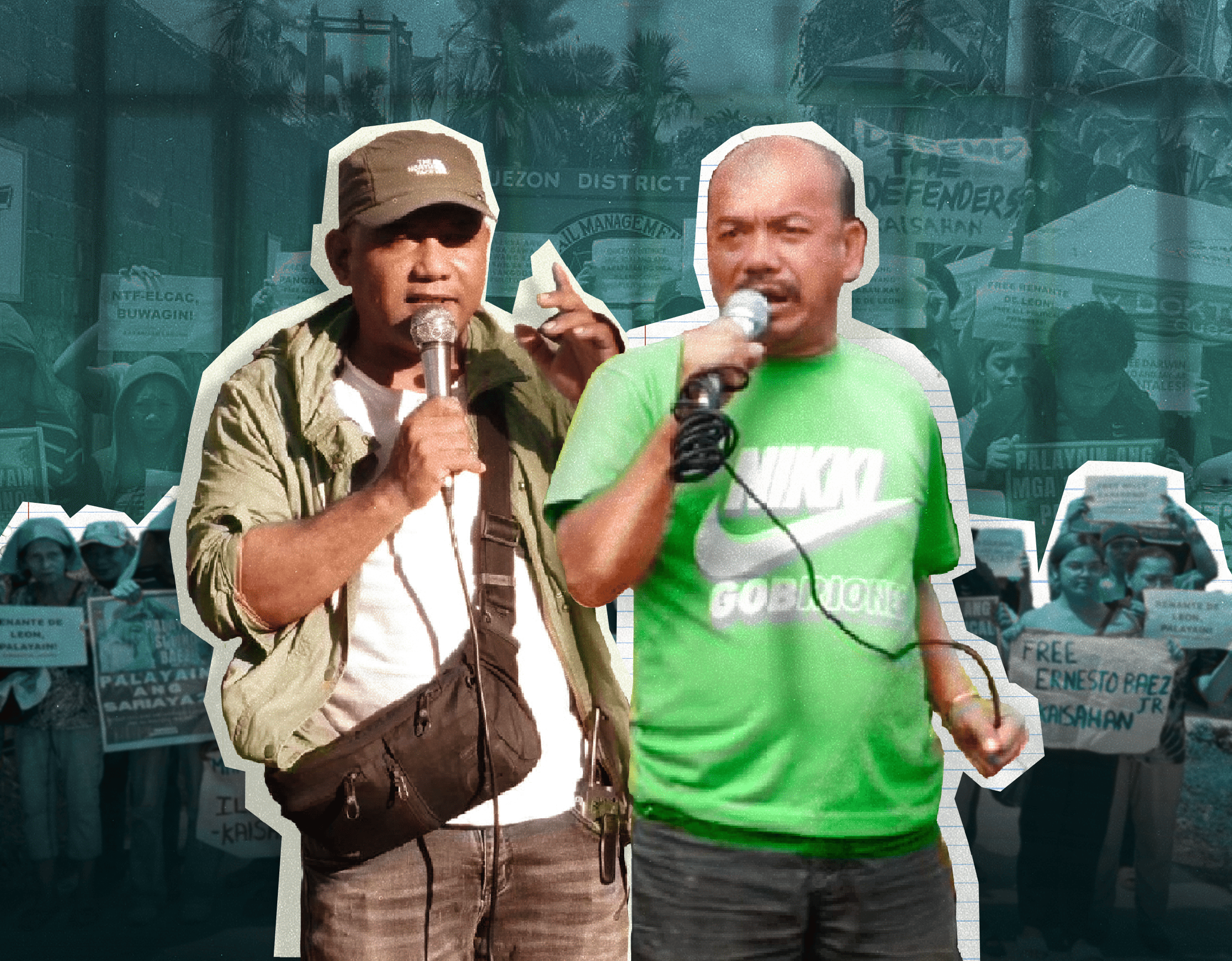

While peasant groups acknowledged the positive intention of the task force, the effort will be futile if the fundamental problems in our agricultural sector remain unaddressed, Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP) Chairman Emeritus Rafael Mariano said.

“Kahit ilang task forces pa ang buuin, kung nandiyan iyong mga institutional and structural barriers—pati iyong mga batas, mga agreements na unequal, disadvantageous sa atin [pero] advantageous sa mga malalaking ekonomiya at bansa sa buong mundo, merkadong miyembro ng WTO, at iba pang mga regional, even bilateral agreements—talagang talo tayo,” Mariano said.

Agricultural Woes

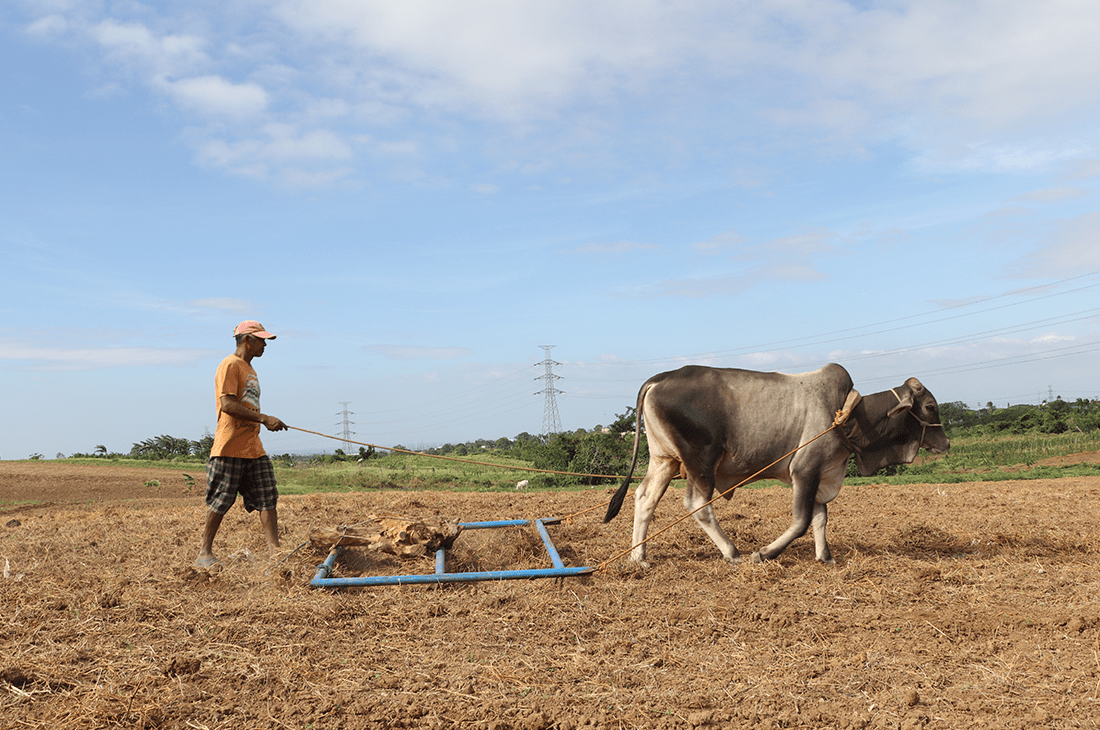

The country’s food producers, who have lately been called food frontliners, confront multiple crises: the year-long pandemic, the devastating impact of the string of typhoons in the last months of 2020, and the market-based, profit-oriented agricultural policies entrenched for decades now.

The lockdowns imposed due to the pandemic have affected the country’s food supply chain since restrictions on movement cause concerns with logistics and transport. The food sector is also still reeling from the damages that amounted to P12.8 billion due to seven successive typhoons late last year, according to the Department of Agriculture (DA).

Despite these, the agriculture sector remains the major economic sector as it registered a -2.5 percent growth rate in the fourth quarter of 2020, amid the national 8.3 percent gross domestic product (GDP) slump, Majah-Leah Ravago, associate professor of economics at Ateneo de Manila University, told the Collegian. The food sector continues to be a major player even with the country’s dip in economic growth, but some pre-pandemic agricultural woes yet unaddressed continue to cause market shortages.

The African swine fever (ASF) outbreak in 2019 already cost the hog industry P56 billion and culled more than 400,000 pigs nationwide, the DA reported. The poultry industry also suffered from a bird flu outbreak, especially in Pampanga last year, resulting in nearly 39,000 chickens slaughtered in the province.

To make matters worse for hog raisers and poultry farmers, the government imposed 60-day price ceilings of P270 per kilogram for kasim and pigue, P300 per kilogram for liempo, and P160 per kilogram for dressed chicken in the National Capital Region (NCR) on February 1. Vendors complained that, accounting for production costs, these prices were too close to the farmgate price of the products.

The price ceiling would have been effective had the government provided support and subsidy for local producers who needed to shoulder all the expenses themselves, from breeding to production, said Casilao.

“Palpak iyong price cap, price ceiling kung hindi naman ito tumatagos doon sa pinakagastusin at subsidyong kinakailangan ng mga hog raisers,” Casilao added.

Amid all these pressing issues confronting the sector, the low budget appropriation for the DA is disappointing but comes as no surprise. From the P4.506-trillion national budget for 2021, the agriculture sector is given a measly P71 billion. Although this appropriation is relatively higher than the average DA budget from 2017 to 2020, the agriculture sector is still not a priority as it is allocated only less than 5 percent of the national budget, for the fifth straight year under the Duterte administration.

“Kabanlintunaan at kabaliktaran na ang pangunahing, pinakamalakas sana na asset ng Pilipinas ay ang sektor ng agrikultura, because the Philippines is basically an agriculture-based country,” said Casilao, pointing out how the Department of National Defense (DND) was given P205.8 billion, nearly triple the DA’s appropriation (see infographic).

The present agricultural issues are a result of the long history of government neglect, Casilao added. The long-time land use conversion policy has affected the market competitiveness of local farmers’ products to be on a par with agricultural imports. Farmlands are being reclassified to commercial, industrial, and residential lands, affecting the country’s food security.

On top of all these issues, trade agreements, disguised as a means for development, have burdened food frontliners even more. The country’s commitment to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trades (GATT) and the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) have liberalized the agriculture sector.

The GATT, a multilateral treaty signed in 1947, was intended to minimize barriers to international trade by reducing tariffs, but it has only pitted local farmers against foreign exporters. Replacing GATT, in 1995, was the WTO, whose AoA aimed to create a fair and market-oriented agricultural trading system. The agreement, however, has hardly leveled the playing field in global trade and instead pushed developing countries deeper into poverty due to the entry of more imported products into the local market.

The unbridled entry of these imports, from vegetables, livestock, poultry, and even to rice, Filipinos’ staple, has adversely affected the local production, Mariano said. In the long term, trade liberalization should be regulated and, at the same, the conditions for small farmers and leaseholders at home should be improved. The government must address the root causes underlying the food sector’s problems that have long trapped food producers and consumers alike in a slump, Casilao said.

“Kumakaharap sa matinding krisis ang pinakamahalaga at pinakaimportante sanang sektor ng ating agrikultura, ng mga magsasaka, na tutugon sana doon sa pangkabuuang pangangailangan ng kanyang mga mamamayan,” said Casilao.

To an extent, a chapter written by Ravago, together with economist Arsenio Balisacan and National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) Undersecretary Mercedita Sombilla, in “The Future of Philippine Agriculture under a Changing Climate: Policies, Investments, and Scenarios” (2019), strikes the same note.

“Ang efficiency-enhancing project or [mga] aspeto ay pwedeng gawin para matulungan ng government yung farmers kasi ito naman ay public goods,” Ravago said, referring to necessary improvements on research and development, road network development, and irrigation and flood control development, among others.

More than these, however, she argued in the paper, another key constraint to rural development has been the country’s ineffective property rights reform via the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) and its later version CARP Extension with Reforms (CARPer).

“The redistribution of private lands was found to have a positive impact in reducing poverty when it was associated with complete titling and transfer, and the effect was stronger when the norm for the transfer was compulsory acquisition of large, private holdings,” read part of the paper.

Both CARP and CARPer, however, despite their good intentions, had proven “poorly conceived largely because of a grossly inadequate understanding of rural development dynamics and the political economy of asset reform under a regime of weak governance.”

The confluence of all these issues in the agrarian sector has come to a head in the wake of economic shocks induced by the pandemic. The impacts have lately been felt most worryingly at the household level, with hunger emerging as among the biggest concerns.

Hunger Woes

With no end in sight yet for the COVID-19 crisis in the Philippines, the hunger situation continues to be alarming. For December 2020, the hunger incidence is at 16 percent, almost double the pre-pandemic figure of 8.8 percent.

The IATF on Zero Hunger, created more than a year ago, aligns with the United Nations’s second Sustainable Development Goal, which aims to end hunger by 2030. It targets to bring back the country’s hunger incidence to the pre-pandemic level, said Nograles.

“Maganda ‘yung goal, ‘yung mission na walang [gutom], zero kagutuman, zero hunger. Statistically and reality-based, it is impossible so long as hindi mababago at hindi maa-address ang mga fundamental problems,” said Casilao.

The Philippines still does not have a comprehensive law to address food insecurity and hunger.

With this, the House of Representatives passed the final reading House Bill (HB) 8242 or the Right to Adequate Food Act, sponsored by five representatives, on February 2. It provides a framework that obliges that state to ensure and facilitate access, adequacy, and availability of food to protect and promote the right of every Filipino to adequate food.

The intent and purpose of the bill are welcome as it upholds and supports the right to adequate food, a fundamental right of every Filipino, Mariano said. However, he added that the full realization of the bill would only be possible by acknowledging the institutional and structural barriers hindering the attainment of food security.

Genuine food security will only be possible by ultimately addressing food sovereignty, according to the 2014 ‘Food Sovereignty Module’ by IBON International and the People’s Coalition on Food Sovereignty (PCFS), a global network of peasants’ rights advocates and grassroots groups.

Food security looks at the “myopic frame” of availability and accessibility of food, while food sovereignty elevates food security to the level of the recognition of the fundamental right of food producers and consumers to determine their food and agricultural policies and control agricultural productive resources, IBON International and the PCFS explained.

Governments would do well to develop food policies and programs that will forward the rights of food producers and consumers rather than the agenda of corporations. But with the Zero Hunger bill, Casilao fears that it may reinforce the government and foreign agro-corporations’ narrow focus on the cultivation of cash crops instead of food crops.

Cash crops, such as bananas and pineapples, are grown for commercial purposes, and food crops for human consumption. The market orientation of the bill may give fewer incentives for local production geared towards public consumption.

“Unattainable sa kasalukuyang kalagayan iyong zero hunger,” Mariano said. “Paano natin maa-attain sa malaunan iyong zero hunger talaga? Kasi iyong zero hunger naman hindi lang doon sa sapat na produksyon o sapat na supply. May sapat bang kinikita ang mamamayang Pilipino, mayorya sa mamamayang Pilipino, para mabili niya iyong food items, staple food sa palengke, at mayroon bang subsidy mula sa gobyerno?” ●

This article was first published online on March 10, 2021.