Faculty adjustments have been nothing short of abrupt since the pandemic began. Teaching methods have rapidly shifted from in-person learning to a hybrid of synchronous and asynchronous instruction. With a new academic year, UP welcomes some of its students back to campus while trudging the experimental terrain of its new learning models.

As the pandemic’s repercussions on our academic lives further take effect, education in the new normal is uncharted territory for all universities. Faculty members carry the brunt of its struggles, who, despite their heavier workloads and unexpected course obstacles, attempt to innovate their teaching strategies every semester.

Rene Principe, a physics instructor at the National Institute of Physics (NIP) shares his first-hand experience: “Talagang ang hirap niya (online learning) kasi nawawala yung essence na two-way yung learning between students and teachers.” In a prepandemic setup, the teacher would prompt questions for the students, and the class could discuss their views on the topic. With this, the burden to share knowledge does not only fall on the professor but also on the students.

In 2020, Principe took on the position of a junior faculty member at the university while on the path to a master's degree. Little did he know that the corners of a classroom would shrink to the edges of a screen as it was his turn to teach in UP.

Principe understands the mental burden the current setup imposes on their students, but as much as he wants to lessen his course’s workload, he has to consider the competencies his class should have after they finish his syllabus. “We always find ourselves at a crossroads on how to balance empathy while preserving the quality of education,” he said.

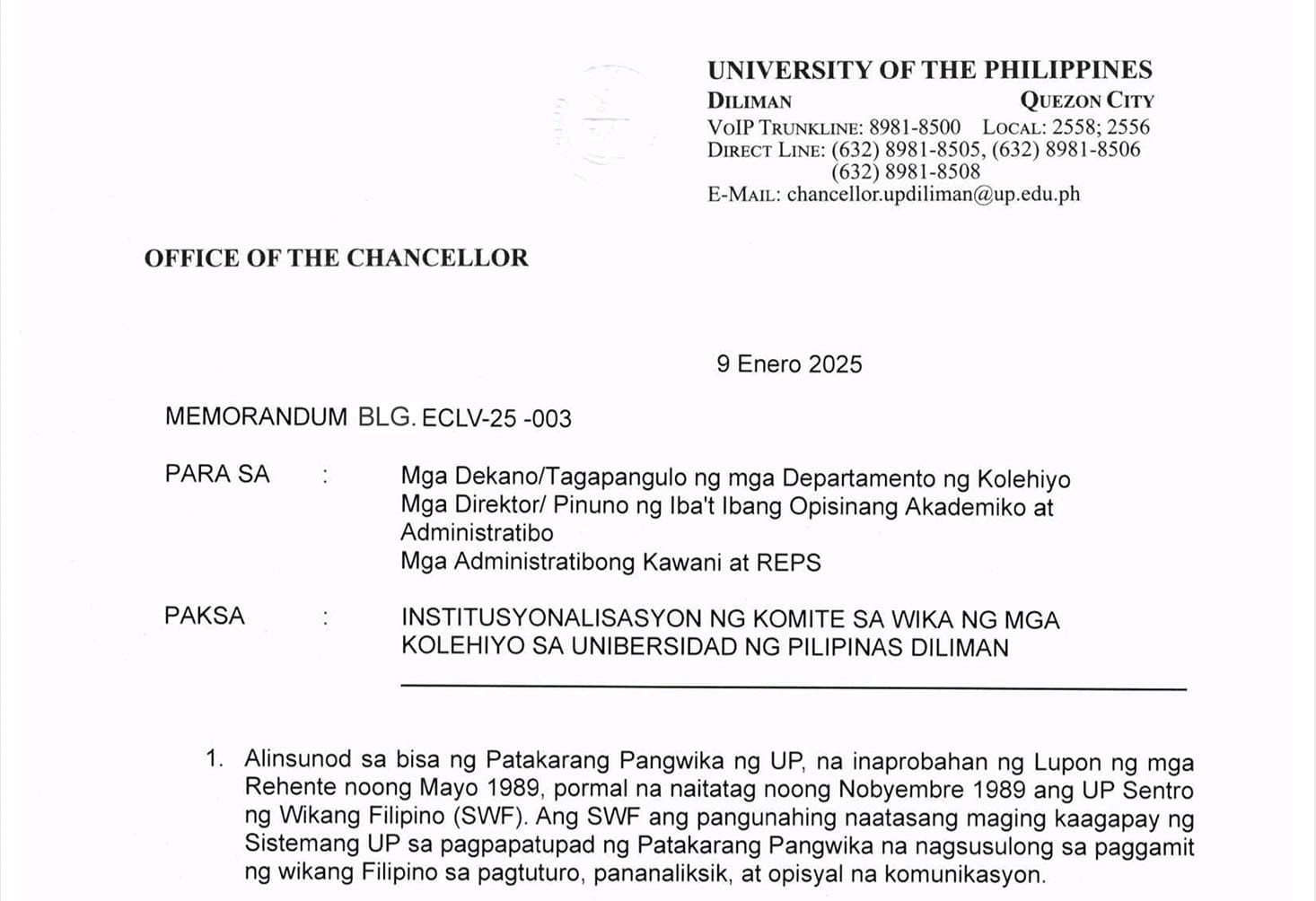

Under the recent memorandum on the UP System’s course delivery and program implementation, the university offers four learning delivery modes for academic year 2022 to 2023: face-to-face (F2F) instruction, distance education, blended learning, and HyFlex learning. The order was a result of the surveys conducted by UP last December 10, 2021, which showed that most respondents were willing to participate in onsite classes with certain apprehensions regarding transportation, safety, health, and the adequacy of campus protocols.

Despite the apparent clamor for the prepandemic style of conducting classes, it is unlikely for teaching to simply revert to its traditional models which had its own set of issues. It becomes important for the UP administration, then, to build from the nuances of various faculty experiences and move onward with pedagogical innovations that will address the crucial problems of remote learning.

Pedagogy in the Pandemic

The faculty’s initial apprehensions about remote learning centered on the aspect of student engagement. For the last two years, instructors found difficulties in maximizing the participation, assessment, and quality of online classes. Each of the UP colleges went through a series of consistent trials and errors every semester in order to optimize their program’s teaching methods in remote learning.

For Principe, the lack of interaction with his students posed the biggest challenge: “We can’t force them to recite, so that alone feels like I’m having a monologue every single time. It’s not the student's fault, it’s not my fault either. It’s really just the situation.”

Productive engagement for both teacher-to-student and student-to-student relations faltered during the pandemic and it is still far from being restored. "I think roughly after two weeks of starting class, the attendance during synchronous sessions declined by almost half,” said Principe.

Much like Principe’s experience, the online set-up has constrained class interactions in the university which prompted faculty members to exert greater efforts to connect with their students beyond scheduled synchronous sessions. Principe mentioned that outside the Zoom call, Discord was an additional channel he utilized with his students to prompt efficient and collaborative communication.

But what makes online learning draining for both faculty and students is that they have to spend most of their time in front of their screens, lacking personal connection to others. Early in the first semester of 2020, Principe recollects spending an entire week working on his computer just to check an entire semester’s worth of course assessments. Provided the soft deadlines back then, some students relented from passing their work until the near end of the semester which caused severe burnout and hurried efforts on the part of the educators. “The worst part is this set-up forces us to choose between well-being and education,” he said.

Distanced from their students, faculty members also found it difficult to verify their students’ performances. Given the lack of supervision, there were numerous cheating incidents in the university where students were found to be sharing course materials in exchange for solutions to their course requirements. At some point, some problem sets and exams, and their answer keys were even uploaded online.

Principe struggles in dealing with such incidents. There were suggestions of creating new questionnaires every time, or coming up with more creative exam problems. This, however, would double the faculty’s load.

“With the amount of workload na tina-try na namin i-juggle on top of our teaching load, not to mention na we try to be more creative every sem, there’s really not much time to innovate,” says Principe. “How do we balance academic integrity with empathy? How do we make the cheaters accountable without compromising the 99 percent who did their exams honestly?”

Ensuring the academic integrity of their exams, dealing with low class participation, and guaranteeing that their students get the education they need require the faculty to think outside the box on how to conduct their classes. But coming up with new ways of teaching and learning proved to be challenging. This is especially true for STEM courses which have the most difficult skills to translate when it comes to remote learning since their traditional set-up relied on hands-on practical exercises, according to a study in the Journal of Baltic Science Education.

In NIP, Principe said that they have attempted to use several technological adaptations such as annotated lecture slides and lecture videos to cater to their students’ needs. But, many still lacked the skills to adapt easily given the limited technological skill, especially older faculty members.

Attempting to solve problems caused by remote learning, the UP administration decided to allow the limited return of students to campus, testing the waters of blended learning.

Improving New Normal Pedagogy

There’s no going back to the pre-pandemic style of learning—this is basically what the UP administration is saying when it released the memorandum on learning delivery modes for the current academic year. Living in a time of a pandemic, disasters, and other crises, the university is gearing up to provide an education that would “develop 21st-century competencies and prepare our students for a disruptive future.”

For the UP administration, its utmost priority is integrating technology into its current modalities, while ensuring support for its constituents. They recognized the urgent academic problems of the past two years as they reviewed and refined the learning delivery of the academic year 2022 to 2023, said Evangeline Amor, the assistant vice president for academic affairs.

Within the constituent units, teaching and learning resource centers (TLRCs) are at the core of supporting faculty members and students. Several programs, training, and workshops have been conducted alongside the digital learning resources made available by the university. One such training program is the Teaching Effectiveness Course offered before every semester to equip the faculty, especially the new ones, with skills for holistic and learner-focused instruction.

The administration is currently working to further leverage technology in the delivery of education and strengthen the full digital transformation of the university, according to Amor. A byproduct of these forward-looking frameworks included the process of drafting the roadmap for this semester. The administration investigated several aspects of the COVID-19 experience such as pandemic adaptations done by the faculty, emerging theories of learning, as well as the adequacy of university facilities.

Consultations with the colleges of the university were critical in determining the modality options for each academic program. Guided by the course learning outcomes (CLOs), learning resources are modified to suit the needs of blended learning. Educators then underwent “Course Redesigning 101,” an extensive course on learning delivery that equipped them with the processes of the learning management system and principles of learner-centered education.

For Dina Ocampo, a professor and a former dean of the College of Education, and a member of the university task force assigned to draft the blueprint for future teaching and learning in UP, the options of learning modalities were able to mediate particular challenges in terms of faculty instruction.

“It provides everybody the choice with how best to teach their classes in relation to constraints in their lives and the diversity of students,” she said. In looking to the future, she believes that education will be personalized and the locations of learning will diversify, but it would not be possible without a contextual response to the faculty’s shared concerns. In attaining this kind of education, it’s important that courses offer more flexibility, purposiveness, and adaptability moving forward.

Areas of Concern

This semester, the UP community’s biggest issue underscores the effective implementation of post-pandemic instruction. Likewise, its multiple prospects would not be translated into a reality without decisive actions coming from the administration and the formation of enabling conditions for learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic has clearly prompted the reevaluation of education and its delivery. Indeed, while the system of remote learning has its own set of problems, it also opened opportunities—that perhaps we can learn beyond the confines of the traditional four corners of the room. But whether the vision UP has translated into actual practice is another story.

For one, the faculty has had differing opinions regarding the contextualization of memorandums released by the UP administration. Principe laments that the challenge to come up with sudden solutions is often pinned on the faculty. He stated, for instance, the implementation of “maximum leniency” during typhoons and sudden outbreaks.

“There is no definite directive to totally excuse students [affected by] storms, or kung totally matamaan ng COVID-19 siya or yung family member. It is always up to the faculty, so walang systemic assurance for the students,” Principe said.

Short of “systemic assurance” for the faculty as well, the vagueness of these memorandums leaves the faculty with little confidence to interpret the fine print. The faculty and students then clash on settling these interpretations, even though they are both victims of the pandemic’s unfortunate circumstances.

“We’re not just talking about education here, we’re talking about the rights of these students. Parang bahala na ba ang lahat [sa] pag-push natin ng quality of education?” Said Principe.

In a petition released by the Congress of Teachers/Educators for Nationalism and Democracy (CONTEND-UP), demands for “clear, concrete, and decisive” policies from the UP administration are of the essence. It stated that while adhering to pandemic protocols, fulfilling the university’s mandate toward higher education necessitates greater efforts in capacitating its colleges to facilitate a safe return to campus. These requisites would include the retrofitting of UP facilities and restoring the vital services that invigorate the full physical return to campus.

Principe added that the bureaucracy in the university had seemingly confounded the process of conducting onsite classes. However, he believes that striving for the implementation of these policies on a unit-wide scale would ultimately ease the faculty’s burden on retrofitting, filing, and documenting these safety measures while also considering the varied contexts of each college.

Notably, the university’s best efforts have not thoroughly translated its preliminary vision into reality. For its disgruntled stakeholders, much of the administration’s abrupt policies still lack clarity, substantial support, and strategic foresight to tackle the problems they are facing firsthand.

Collective Aspirations

As an instructor who started teaching when the pandemic struck, Principe’s genuine hope would be to teach in a classroom before he ends his master's degree. He recalls that the once bustling streets of UP Diliman were nothing more than an empty shell of its former spirit without the students and faculty who have kept the campus alive.

As the university moves forward, CONTEND-UP calls on the administration to examine and propose policies that enable effective pandemic adaptations—in terms of health, transportation, and other facilities—that instigate the conduciveness of hybrid and onsite education. This would include hastening the development of UP’s retrofitted facilities, the accessibility of COVID-related health services, and the resumed operation of jeepneys and UP vendors within the campus.

Similarly, the UP community collectively aspires to return to campus, despite the initial disempowerment brought by the pandemic’s restrictions. Their problems, however, will not merely dissolve once face-to-face classes start anew. For UP education to live up to its holistic prestige, the administration must look further inward.

Ocampo finds that “perspective taking” is an essential tool to better understand how to go about the issues in question. As the space of learning diversifies, the challenge to review and refine these processes will only become greater but as one UP community, it is a shared responsibility between its constituents and administration. In Principe’s words, “Mas magkakampi tayo dito halip na magkakalaban.” This means that policies concerning the welfare of stakeholders are not created from top to bottom. Instead, the administration must place greater consideration on proposals forwarded by the faculty and students themselves. We also need to be able to openly assess our experiences and air out our grievances so policymakers could improve their programs.

Efforts to better UP’s learning pedagogy cannot stop at the introduction of hybrid learning. Post-pandemic problems in education can only be addressed once it learns from the experiences of the UP community, its current consultative measures are but steps toward quality education that is more equitable and inclusive in the new normal. ●